JLappin Photography

JLappin Photography

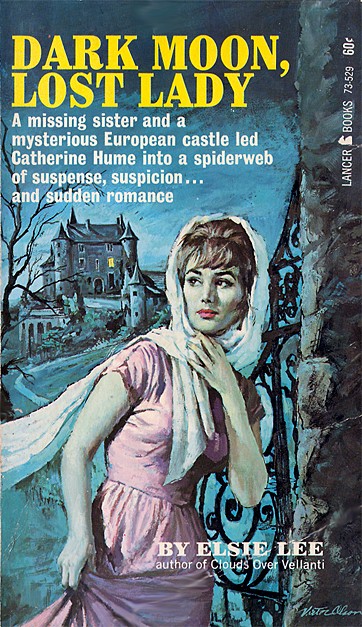

Shannon Walton and Mark Pergolizzi in A Doll’s House, Evergreen Theatre.

Inflatable doll

Lover ungrateful

I blew up your body

But you blew my mind— “In Every Dream Home a Heartache,” Roxy Music

“In Every Dream Home a Heartache” — It’s gotta be one of the best moments in pop music, doesn’t it? After 3-minutes and 5-seconds of suspenseful, droning, horror-show organ overlaid with a moaning Better Homes & Gardens-inspired monologue about architecture and artificial love, it gives way — with all the subtlety of a dam breaking — to this fluid, consciousness-expanding guitar solo. The tipping point is Brian Ferry’s final, table-turning revelation, “I blew up your body, but you blew my mind.”

That’s so Torvald.

Forgive the aging rock critic indulgence, but this song’s been stuck in some remote corner of my brain since a new edition of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House showed up in my mailbox last fall, and my dutiful thumbing-through turned into a reading adventure that took me from August Strindberg to Eugene Ionesco. It was a head-trip that left me thinking I’d missed some really important things that make A Doll’s House just a little darker, and more up to date than I remembered it being. Today it strikes me as less the domestic drama about a woman who’s had enough, and more like a psychological horror story about a houseful of robots with varying degrees of self-awareness — caught in a loop where desperation creates awareness and awareness magnifies desperation. So many of the themes relating to identity, information, and awakening at play in Roxy Music’s perverse vision of domesticity are right there in the script. That goes double for headier contemporary diversions like West World. It’s all right there in Ibsen’s surprisingly concise blueprint.

Although it doesn’t break much new ground, there’s something about CentreStage Theatre’s bland, not bad production of A Doll’s House, that drives home just how modern this 19th-century script remains — and how much closer it may be in spirit to Eugene Ionesco’s absurd farces than it is to Chekhov’s lyrical studies in epic domesticity.

Director Marler Stone has assembled a competent, clever, not always convincing cast to take on Ibsen’s challenging script. Shannon Walton’s Nora is a spunky, focused presence at the heart of a production that could stand a good deal more spunk and focus. Her dark red dress, a perfect design touch in a shoestring show that needs unifying visual themes. You can easily imagine her on the cover of a Gothic romance, running away from some big storybook house — but I’ll come back to that later.

After years off the scene Memphis character actor Mark Pergolizzi has been making something of a comeback, and, as nora’s husband Torvald, he’s very good at revealing the oppressive fantasy narrative and dominance games that underpin all the man’s superficial doting. It’s hard not to imagine what Pergolizzi and Walton might do wth more focus and material support.

The primary difference between Nora and Torvald may not be opportunity. She is evermore aware of the cheaply-gilded cage they’re both trapped in — a cage baked from the same recipe (controlled economies + blind justice) that’s given us other outlaw protagonists like Les Miserables’ bread-stealing Jean Valjean. Nora committed a serious crime to save her husband while simultaneously having an above-means Italian holiday for her and the fam! She’s well-intentioned but “no saint,” as nightly news reports so often say of alleged wrongdoers who’ve been blown away by trigger-happy cops for no apparent reason. Nora’s not-so-little secret preserves Torvald’s developmentally arrested illusion of domestic comfort while her own expanding awareness makes her one of the two least doll-like characters walking in and out of Ibsen’s money-eating house of mystery. Her antagonist Krogstad is similarly woke, and longing for the legitimacy he’s denied by a culture where mistakes — like the one Nora’s made — make it difficult to redeem oneself, even by hard, honest work. Like the subject of a Merle Haggard song, past mistakes mark him like a brand, becoming pretext for petty, baseless discrimination.

“My sons are growing up and for their sake I must try and win back as much respect as I can in the town,” says Krogstad who, in reality was dismissed because he was overly familiar with Torvald, calling the petty, easily offended manager by his first name. “This post in the Bank,” he says, “was like the first step up for me—and now your husband is going to kick me downstairs again into the mud.”

Though never as committed as he might be to the urgency Krogstad clearly feels,” Marcus Cox does a good job sidestepping potential melodrama while meticulously unpacking his complaints and leveling demands. With situational exceptions, everybody else in the drama operates like pre-programmed robots running a limited number of darkly comical scripts, adapting those prerecorded narratives to situations as they arise, and breaking down into a repetitive, “does not compute” sputter when there’s a glitch in the program. A glitch like Nora.

Nora’s Stepfordian friend Mrs. Linde, dutifully rendered by Leah Roberts, proposes an inoculation: “This unhappy secret must come out,” she says, advocating for a dose of the one thing known to set folks free. “All this secrecy and deception, it just can’t go on.” Linde runs on convention. Without work she couldn’t live because she’s never known another way of living. “That has always been my one great joy,” she say chillingly. “There’s no pleasure in working only for yourself.”

Though he’s given very little action to drive, Dr. Rank’s almost literally the play’s backbone and also the most metaphoric tool in Ibsen’s toy box. It’s the allegorically named doctor who makes us aware of the drama’s architecture when he diagnoses Krogstad’s “moral disease.” Rank knows from disease, having been born with “spinal consumption” (syphilis) transmitted at conception by dear ol’ dad. Rank’s built of stock lines peppered with the unique gallows humor of someone born suffering who knows he’s exceeded his expiration date. He’s a repellant double reminder as to why society values domestic convention and that it fails anyway. Skip Howard’s a little stiff in the role, but consistent and clever enough to find the laughter, if not the life so often missing from Ibsen.

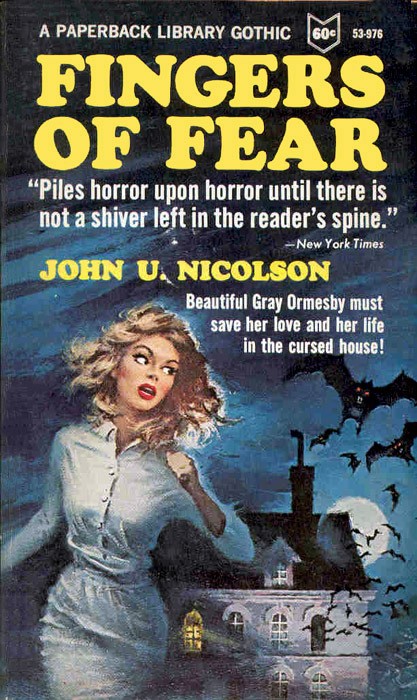

I started this review with one pop culture reference, I’ll close with another digression that may not be relevant — I think it is. In the history of paperback romance novels there may be no single greater cover trope than the image of women running away from perfect storybook houses in varying degrees of decay. You know, like this.

And this.

And this and so many more…

What does it mean? I can’t say for sure, but the imposing homes make good metaphors for stability, comfort, traditions, and — in the American idiom in particular — dreams. Like Torvald’s bloodless repetition of romantic fantasies plucked straight from the pages of a penny dreadful, I think it’s all got something to do with the opening line of Jane Austen‘s Pride & Prejudice — “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

Not a man, mind you, but a man possessed.

This brings us back to the top of the page and comments in the new edition about how the translators chose to keep the title A Doll’s House, even though it might be more accurately translated, “A Home for Dolls.” The first, most conventional title, makes the house subordinate and the doll possessive in a way Nora never could be. The latter shifts emphasis from the possessor to the home itself. While I advocate for economy and firmly believe the only necessary set piece in this show is the door Nora slams on her way out, CentreStage’s production would have benefited from more structure of almost every kind. The play’s not called Torvald, and the sputtering, isolated man Nora leaves onstage, imprisoned by convention at show’s end, might be better understood with some visual context — some real estate. This closing scene presents us with same image on the cover of practically every gothic romance novel ever printed, after all. Ibsen, writing 100-years after Ann Radcliffe launched the gothic genre with The Mysteries of Udolpho, and 100-years before the pulp romance boom, just turned the picture inside out.

CentreStages A Doll’s House may be finished, but it’s not quite complete. It’s still a solid reminder of why, at a time when “classics” usually means Shakespeare, and visits with artists like Strindberg and Ionesco are few and far between, Ibsen also matters.

A Doll’s House is at the Evergreen Theatre through Oct. 1.