Emmanuel McKinney’s a certifiable natural resource — a smart, unaffected actor with incredible range. And, not to sound too much like Howard Cosell though it may be more fun to read the last half of this sentence in his voice, every single time I think this young actor may have finally met his match he steps up his game and astonishes. In Fetch Clay Make Man McKinney doesn’t even try to mimic the “Louisville Lip,” Muhammad Ali, but finds the heavyweight champion’s rhythms, and commits to being pretty. McKinney steps right into Ali’s big, white Everlast boots wearing the character as lightly as a terrycloth robe. It’s always good to see a strong actor get that kind of workout even if Will Power’s historical fiction is more interesting than well-made.

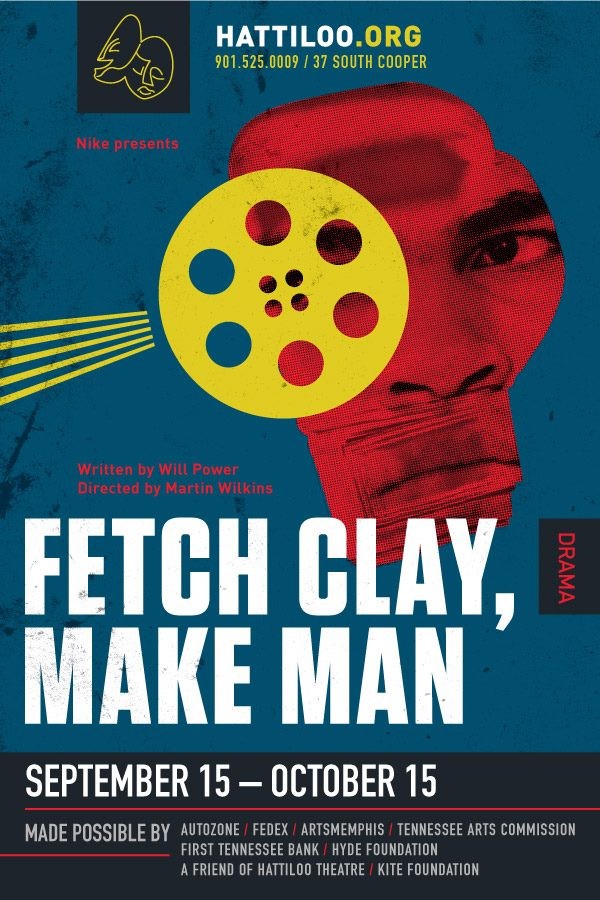

I’ve already written about Fetch Clay‘s three most dominant personalities, Ali the champion preparing to take on Sonny Liston, Stepin Fetchit, a delegitimized black film star famous for playing demeaning stereotypes, and legendary boxer Jack Johnson who may be the play’s most important character though, like Godot, he never actually appears. I won’t rehash all that, other than to set up the show, which unfolds in the aftermath of Malcolm X‘s assassination, just before Ali’s rematch with Liston. It explores the strange alliance and unexpected bond that formed between Ali and Fetchit, as the rhyme-slinging boxer sought to unlock the secrets of Jack Johnson’s “anchor punch.” It’s a conflict-laden meditation on identity, and what it means to be a black celebrity in America.

Johnson’s mythical punch works like a MacGuffin, creating opportunities for Ali and Fetchit to play cat and mouse games — to spar. It’s not the mismatch one might imagine, though Fetchit’s influence on Ali’s wife Sonji Clay sets up a culture clash, and tense situations with Ali’s brothers in the Nation of Islam who see Fetchit as the perfect Uncle Tom.

Stephen Dowdy is similarly convincing as Fetchit (AKA Lincoln Perry), though his flashbacks to early Hollywood feel tacked on — a bit of contextual embroidery that’s never fully woven into the bigger narratives. It’s never clear how high the stakes are in his lopsided partnership with Ali.

There’s something Twelfth Night-like about Fetch Clay with Ali standing in for Duke Orsino, finding himself suddenly in need of his not-so-foolish fool. Though he’s suited and bow-tied instead of cross-gartered Simon, Ali’s Nation of Islam brother and bodyguard is this story’s uptight Malvolio. Unlike Shakespeare’s Puritan, Simon won’t be made a fool. Not more than once, anyway. Justin Hicks keeps Simon’s anger and instinct bubbling just under a cool surface, and brings as much tension as he can to a show that needs more. Jessica Young-Steward’s similarly fine as Ali’s wife, whose evolving identity might be more compelling she wasn’t trotted in and out of the story for added drama.

Ron Gephart also appears in an uncredited role as the memory of Fox Film founder, William Fox.

Hattiloo director Martin Wilkins has delivered a lean, actor-oriented production filled with characters we want to watch even when Power’s story gets fuzzy and repetitive.