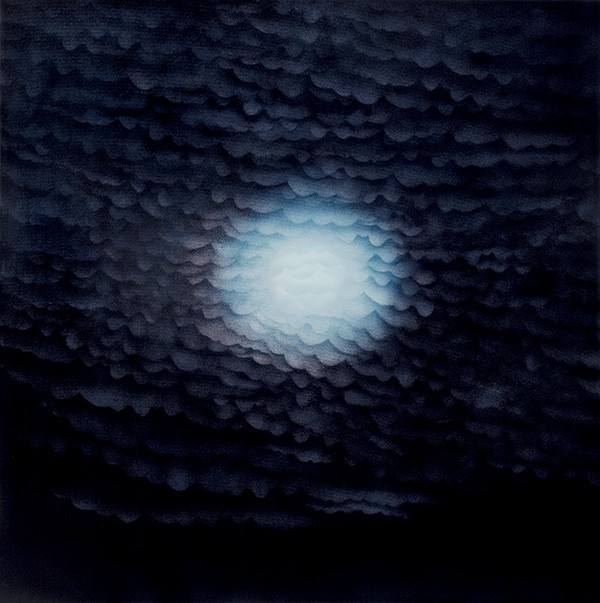

Veda Reed, Three Black Clouds, at David Lusk Gallery

If “Cloud Atlas” wasn’t already the name of a time-spanning science fiction epic, it would make a fitting biography title for Veda Reed, a painter of note who’s always looked to the sky for inspiration.

Reed’s not from around here. She’s also Memphis to the core, having arrived in town before Rock-and-Roll, with no great plans to be an artist. The place spoke to her, inspired her, and showed her the way forward. She enrolled in the Memphis Academy of Arts (later MCA) before its move to Overton Park, and graduated in a class of three. She remembered the school as a place that quietly affected change in the community.

Memphis Flyer: You have a great arrival story, and I know you’ve told it many, many times. Would you mind sharing it again.

Veda Reed: My father was a pipeliner. Do you know what a pipeliner is? They were the crew that laid all the natural gas lines across America. and he work for Williams Brothers out of Oklahoma City. But anyway he was traveling all the time and moving. Laying the gas pipes. and he happened to be in Memphis 1 summer the second year after I got out of high school and I came to visit him. my parents were divorced who they didn’t live together and I didn’t have anything to do with my dad had a new Studebaker and I would take it out everyday and wander around Memphis. I drove down Adams Avenue.. I never seen a Victorian building. over the door to the Memphis Academy of Arts. So I stopped the car and got out. and I came back out register for the next semester. The woman who was the registrar, I asked her what is this place. She said it’s an art school. Would you like to go here? I said yes. And she proceeded to fill out a schedule of classes for me. I had no portfolio, nothing. I just walked in off the street. And I had had one class in life drawing when I was spending some time with my aunt in Salt Lake City. She asked if I’d had any previous experience and I said yes I had a life drawing class. She said oh well you can take Life drawing with Ted Faires. So I had a schedule that was 5-days and 2-nights. And the tuition was $175. And I said, “But I don’t have any money.” She said, “That’s okay, just have your father write as a check when you come to the first class.” So I did that. I was not allowed to drive a car anymore. But that’s my experience. I knew the minute I saw that side of that building, this is where I was supposed to be.

Did you have any background in art at that point?

I had not had any art training at all, really. My little high school in Oklahoma didn’t have our classes. My aunt, my mother’s youngest sister, wanted to be an artist and she finally became a fashion illustrator. Back then they had illustrators for newspapers. So when I went to stay with her after I got out of high school, she was teaching at a little school called The Art Barn in Salt Lake City. And she took me with her and I had my first drawing class.

And you took to it naturally?

Actually, I was not very good at it. But I was inspired by her so much that, whatever she wanted me to do, I would do it. It felt good.

Were you always so spontaneous? Or, is impulsive the better word?

I don’t think so. But something happened to me when I saw that sign. I needed to find out what this place was.

Can you paint a picture of campus life? The culture of the college?

It was a very small school. It also on the GI Bill, so there were several veterans there. Some of them in wheelchairs. Ted Rust was the director. They didn’t call him the president then. He got there in1949, and I was there in 1952. I had a memory of there not being more than 36 students working for a degree. There were many people in the community who came to take classes. And we were just one big happy family. Everybody knew everybody. The first time I ever met Ted Rust, our director, I was sitting out under the wisteria, which was profuse.

It’s beautiful, but it’s a menace!

Oh yes. And I should have been in class too. Ted Rust looked at me and said, “Aren’t you supposed to be in class?” And I said. “Yes sir.” And I got up and went. But we became very good friends. Most of the students were friends with the faculty.

I know the school offered paths for fine arts, and design, and also for advertising. Was this a competitive division?

Everybody had to take the foundation course. I think that’s been one of the strengths of the school. Everybody had to learn how to see. Which was done through drawing, and design. You had to learn how to think. So everybody took those courses. Fine Arts and the advertising had friendly competition. We called them “the business students.” But there was no putdown of either. And we had very strong advertising classes. Also interior design was taught.

Nightfall: Clouds and Moon 2006 from Veda Reed’s “Day into Night”

I’m familiar with the big changes. The moves, name changes etc. What are some of the other notable changes over the years, in your opinion.

Of course I’m old enough to proclaim that I hate change. I don’t apologize for that. But I do recognize the value of all the changes that have been made. Some, I think we’re better than others. I won’t continue on that.

But we should talk about some of it. Was the transition into Overton Park a smooth one?

It was a smooth transition. And it was very exciting. Some of us hated to give up the old beautiful buildings though. But the park is so wonderful, and the building was an award winner so the move was very smooth. Everybody at the old Art Academy packed up their cars, whatever vehicle they had, and move boxes into the new building. It was only half the size it is now. Another thing that changed once we got into the new building, is we started offering more liberal studies in house. The old school didn’t offer liberal studies. You had to go elsewhere if you wanted to work for the degree. Ted Rust got the college accredited, and we began working on getting all the liberal arts classes required for the degree in house instead of having to have students go elsewhere.

I remember when MCA students would also take classes at Rhodes and CBU. There was a consortium for students interested in classes that weren’t being offered in house.

When we first started that I was a Guinea pig, I guess. I went to Rhodes to take one of the classes Jack Taylor was offering. I think I was not a good person to send. I didn’t pass the class. Something about physics. A physics class he thought artists might enjoy.

What else do you remember about the early days in Rust Hall.

The school was actually designed for the courses we were teaching at the time. For the specific courses. The basement area was a very long and narrow studio devoted to fabric design. We had these long printing tables and used to joke about it and call the bowling alley. As Time passed and studios got rearranged, things changed. I believe the original building was only half the size it is now. It was built to hold about 200 students. Often we would have as many as 24 students in a classroom and that never bothered me. Student seem to work off each other. And I hated the name change. it never should have happened. Oh well.

A lot of people hated that, I think, but I understand. It was a response to all the private Christian high schools that sprang up after desegregation. So many of them took the name “academy.” I can understand why MCA might have wanted to avoid confusion in the same way Southwestern at Memphis became Rhodes because there are so many schools with Southwestern in the name, and the name only really makes sense if you’re recruiting in Tennessee only.

Speaking of desegregation, one of the things that happened when the Art Academy move to the park was this. The park was segregated at the time, you see. African-Americans could only come on Thursdays. Ted Rust told the city, “We are a school. We have classes every day and the students must come.” It’s so hard to think about a group of people only being able to go somewhere one day a week. It is just incredible. And I the park was desegregated soon after that.

Are you working on anything special now?

I am. I’m preparing new work for a show in 2018 for my 85th birthday.

——————————————————

A Conversation with Dolph Smith

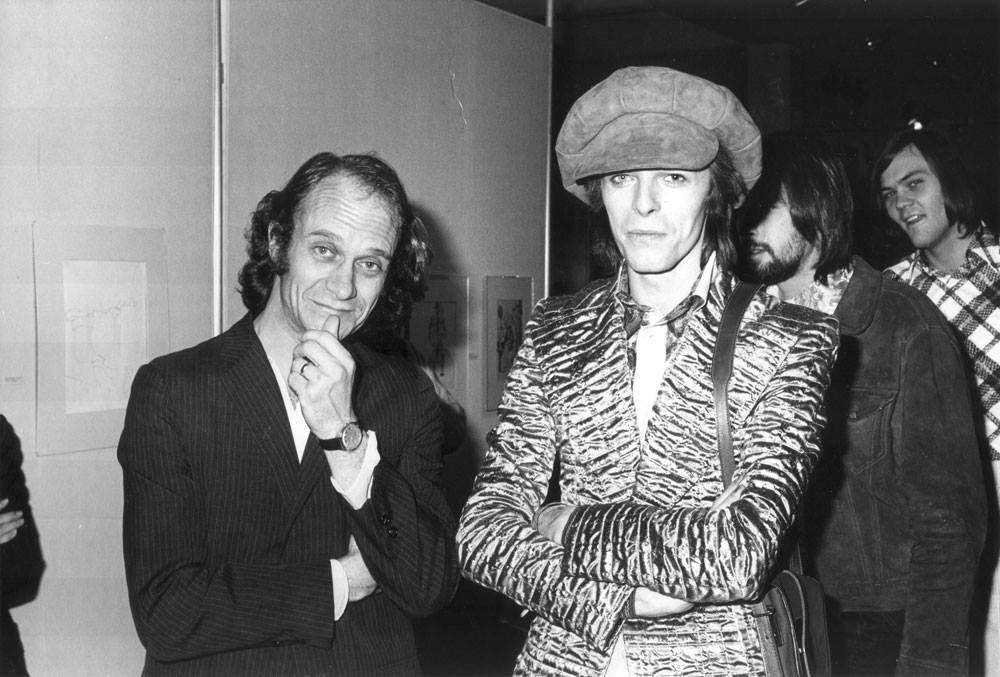

Dolph & David at MCA

Dolph Smith was unable to enroll in person, so his mother did all his paperwork at the Memphis Academy of Art. The person helping her was Veda Reed. Smith, a painter, bookmaker, educator, and builder of nifty little buildings, was among the first students to receive a diploma after the school moved to Overton Park. He graduated in a class of seven.

Memphis Flyer: I’ve enjoyed your work for so long I hate that our first extended conversation is the result of such bad news.

Dolph Smith: It’s just heartbreaking. There’s so many of us that still have our roots in that place. I don’t think I’ll ever accept it.

I know you at least started when the school was still on Adams.

I was a GI in Berlin Germany. Something happened that told me that I needed to go to an art school. And bless my mother’s heart, I woke up in the middle of the night and called her. And I asked her to find me an art school. And she did. She found the Memphis Academy of Art on Adams. When I was at the bottom of a troop ship coming home from Germany she walked up those broken steps on Adams and Veda Reed signed me in. That was in 1957. What’s amazing is that fate’s a big factor in bringing people to an art school. It’s not like you want to be a fireman when you grow up. Things happen to you growing up and you come to it. What a blessing. I’ve loved every minute of it.

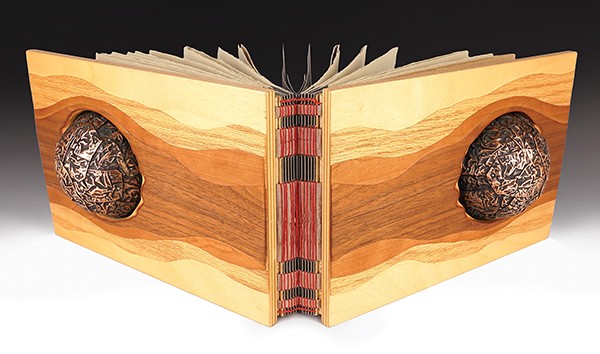

Smith’s Buoyk

What was student life like when you got there?

It was very intimate then because we were just so close to the faculty. that’s when Ted Faiers was there and Burton Callicott and that whole lineup of iconic people. And Ted Rust. It was just a warm little place. Of course every now and then a little bit of plaster would fall out of the ceiling, but that was part of it. We had a little sandwich shop down in the basement. That’s where we had our lunch. Ted Rust would come out of his office and walk out to the volleyball court and we’d have a volleyball game every afternoon.

That does sound close-knit.

It was. We were so close. And you know the classes were small. I was there in the last couple of years on Adams, and when they built the new school I was in the first graduating class there in Overton Park. I think there were seven in my graduating class.

What kind of balance was there between classical fine arts training and commercial and industrial design?

We took everything. We had calligraphy, Burton Callicott taught that. That was one of his geniuses. There was a pretty good advertising design department. One of the leaders of that was Jason Williamson. He was a great watercolor painter. I graduated with an advertising design degree and got a job pretty quickly at a small art studio downtown. Of course, over the years I got the urge to pick up that brush. And that led to teaching nights at the college. We had a big community education program. I think it was in the hundreds of people down there at night. It was just a thriving place. I did a good bit of that. And Ted Rust asked me to join the faculty. So I left a day-to-day job and went to the college. Which was then still called the Academy.

What were academics like?

When I went through as a student I had to go to Memphis State to get 30 hours of academics because they didn’t teach any of that. It was all painting, throwing clay, even making mosaic tile as a class, and we all took that. So we had to put things together in two places. We had to have a language class so I took German because I’d been in Germany and figured I could ace that class. But I ended up with a C. I didn’t ace it at all. That’s how we put together the academics, which worked out fine, I guess.

And there was no such thing as campus housing…

I lived on a street called Cowden out there, over towards where the Memphis State campus was. We all had to find places to live, that was just part of it. I had the GI Bill, which was a help. A big help. And I had to have a job. I did some part-time work. One of them was at the Methodist Hospital where I was born. I worked nights at the admissions desk, and I’d go to class the next day. I’d be in life drawing working on a figure and she would pose for 20 minutes, and she’d take a ten-minute break, and I would take an 8 minute nap in a sling chair in the studio, and my friends would wake me up, and then I’d draw for another 20 minutes, and then I’d go take a nap.

A thing that really strikes me about this news. Art and artists are really at the core of Midtown’s identity, and a big part of that is directly related to the presence of MCA. You watched a lot of that grow. I don’t think I have a question here…

So many of us put down roots under that building, and so many of us are still growing from the roots attached to that building, and to that space. I think you’ll enjoy this… We’re being cremated. And the first place I wanted my ashes to be thrown was off the balcony at the Memphis College of Art. Outside the room where I used to teach. So many are gone. Burton Ted. Veda And I are the last of this old breed that go all the way back. It’s just part of our very physical selves. Not just mental but physical. And I’m not giving up.

Dolph Smith’s Fertile Attic

Watch The Memphis Flyer’s News Blog and Fly on the Wall for more web extras related to this week’s cover story Art of the Deal:The extraordinary rise and precipitous fall of the Memphis College of Art

[content-1]