The phone call in late February was to a house near Woodstock, New York, a town in the frigid Catskills. The voice on the other end of the line belonged to Holly George-Warren, here to talk about her latest book, but she was remembering her friend Melinda Pendleton, who had passed away in New Orleans the week before.

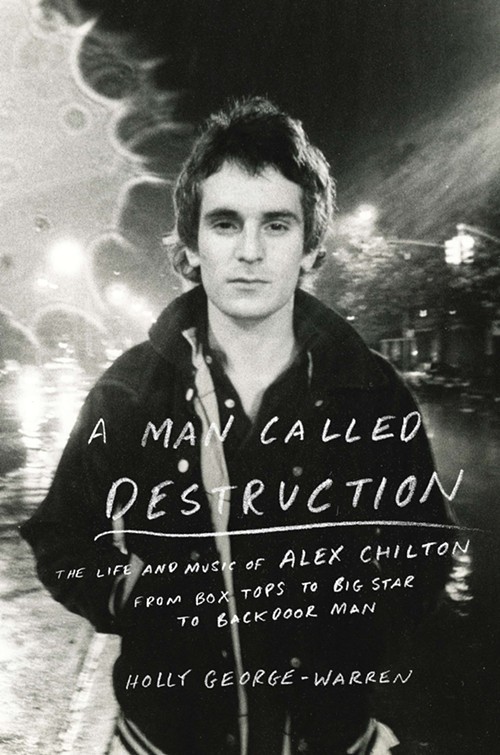

The official publication date of George-Warren’s A Man Called Destruction: The Life and Music of Alex Chilton, From Box Tops to Big Star to Backdoor Man (Viking) was still weeks away. But the author had just learned that the book was already into its second printing — a book that George-Warren will be discussing and signing in Memphis at Crosstown Arts (438 and 430 N. Cleveland) on April 2nd.

[jump]

The first topic the day of that phone call wasn’t, however, the main topic: the Memphis singer who’d had a national #1 hit when he was still a student at Central High and serving as front man for the Box Tops. And it wasn’t the Memphis singer/songwriter/musician who was a founding member of Big Star, the influential band that helped to define the term power pop in the early ’70s. Nor was it the performer who went on to do a wide range of solo work and additional work with Memphis’ Panther Burns. The opening topic was that late friend of the author’s. Just so happens, it’s Melinda Pendleton who introduced Holly George-Warren to William Alexander Chilton.

“It’s been a tough week,” George-Warren admitted. “Melinda had an encyclopedic knowledge of gospel, country, and blues. She was a writer and a deejay at WWOZ in New Orleans. In the late ’70s, she’d moved to Memphis with musician Peter Holsapple, and during that time, Pendleton became friends with Alex.

“And I remember: Melinda and I traveling around the country, listening to cassettes — Big Star songs, Alex’s album Like Flies on Sherbert — and in the streets of New Orleans, we hear, ‘Melinda, is that you?’ It was Alex. He’d just gotten off work as a dishwasher.

“He became our tour guide to all the bars of the French Quarter, even though he was not indulging at all. He was goading us on — try this … try that. By 2 a.m., we were ‘gone.’ Alex and his girlfriend led us to our car, which had been towed, so they let us crash at his apartment. And that’s the night I threw up in Alex’s sink.

“Alex had this incredible mind. When you think of the zillions of people the guy met … I mean that time in New Orleans was a very fleeting, brief encounter, and then two years later, when Alex was touring again, I went to a gig of his in Hoboken. I brazenly said, ‘Hey, remember me? You want to produce my band, Clambake?’

“Alex always had a soft spot for the King, so I don’t know if it was my band’s name [lifted from the title of an Elvis Presley movie], but he totally remembered me and my birthday, because of Alex’s thing for astrology. He said he’d produce us for $500 and a lamb chop dinner.

“We worked with him in ’85. We got to do a gig with him. Every time he played in New York, I’d go. You could hang out with him afterward. He crashed at my apartment on St. Mark’s Place — and I did cook him that lamb chop dinner.

“If Alex was in a good mood, he could be an incredible host and great conversationalist. He liked to talk about all kinds of things. Then he’d have a day when he was not at all in a good mood and didn’t want to talk much. You kind of never knew what you were going to get.”

Tell me about how you came to write this biography. What it meant to you personally when you learned, in 2010, of Alex Chilton’s sudden death.

Holly George-Warren: I was in Austin at South By Southwest, and I’d been calling Alex, because two of the girls from Clambake were in Austin too. I was trying to arrange for us to get together. I kept calling his cell phone and getting this weird busy signal.

That afternoon, I was in a shuttle van on my way to see Wanda Jackson, one of my idols, and there was a guy in the van, talking in a Memphis accent, talking on the phone, totally upset, going, “Oh my God, no.” He said to us, “I’m sorry to have to tell ya’ll that Memphis has just lost another one of our great musicians.”

It was devastating. This was after Jim Dickinson died. I even thought at first that Alex’s death was a hoax. I thought there was that chance, because as much as Alex loved Austin — Austin was one of the first places he started playing again after the whole Big Star thing — every once in a while, it could get on his nerves.

I’d brought Big Star to play in New York in celebration of a book I wrote, The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll. My literary agent, Sarah Lazin, knew I loved Alex. She said, “Holly, you’ve got to write a book about him.”

In the beginning, I had mixed feelings. Alex was very private, so I didn’t want to do anything that would offend him. But at the same time, I knew that as much as he didn’t like a lot of the trappings of fame — he hated people fawning over him — he was a great, great lover of books. He’d read some of my books. He respected writers. He respected well-written books. From what I knew, there hadn’t been anything thorough on Alex.

Alex loved Robert Palmer, the music writer. He would have jumped at a book about him by Robert Palmer. I’m by no means anywhere near … I don’t have Robert Palmer’s knowledge or writing ability. I still thought … I concluded it would be okay. Alex deserved a book about his music, because it hadn’t been looked at in all its depth and breadth. And there’d been a lot about Big Star but not that much in depth about the Box Tops.

I wanted to apply the same professionalism and depth and research as I had in my Gene Autry biography. Alex deserved that, and I’d been in the same milieu. I knew the musicians. I knew him. I knew the music. I knew it would be hard, and, lo and behold, my agent tested the waters and contacted the major publishers in New York to see if there was interest. Something like a dozen publishers said they’d definitely be interested in seeing a proposal, and five publishers made an offer. That to me was so exciting … to see that the world of New York book publishing knew who Alex Chilton was, his great value to popular culture and music.

My editor at Viking, Rick Kot, was already a big fan too. It was a great, powerful experience to get that support. I felt that the stars aligned to make this book happen.

You spent time, then, in Memphis, researching, interviewing?

Quite a bit for the book. But my first trip was in the ‘70s, and my first big experience was with Melinda in ’82. I love the city. It’s an amazing place to be.

When I do a book, I like to see and experience the place that informed the person I’m writing about as much as I can. In the case of Alex, see the houses where he lived, the different dives. I “got’ the scene in Memphis.

Those who knew Chilton well … were any of them reluctant to be interviewed?

Some decided not to. You go through a long period of mourning. You feel different each week … how you want to interact with someone who’s writing a book. Alex knew so many people, and there were more people for me to interview, but my editor would have killed me.

I did try to cover one or more people from all the phases of his life, and the memories have really varied. There’s a Rashomon quality to what people remember. There could have been three people in the same room as Alex, and all three would report a different story of what happened. That’s the tricky part. I know that from my own life.

Chilton and fellow Big Star member Chris Bell, who died in 1978: How would you describe their working relationship?

Being a huge music fan and amateur musician myself, I’ve been around that dynamic. It’s a very changeable dynamic. In the beginning, Alex and Chris felt they were soul mates musically. They really connected. Each thought the other complemented his own work. The first Big Star album bears that out, a real collaboration. Alex’s songs were filled out by Chris and vice versa. When Alex talked to Bruce Eaton for Eaton’s book about the album Radio City, Alex even said in no uncertain terms that #1 Record was his favorite Big Star album.

Part of that Big Star experience for Alex was really joyful, as it was for Chris. But then, all these other elements came into it: substance abuse, competition, professional jealousies. Alex and Chris had such different experiences. Alex had already been through the whole Box Tops thing. You can’t underestimate the effect that had on him. It had been liberating, but it imprisoned him too. With a few exceptions, he’d musically had to toe the line.

Did you participate in the recent documentary “Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me”?

I met the filmmakers. They were helpful. We shared information. I was interviewed for the film, but I ended up on the cutting-room floor. Thank God.

For my book, I tried to use some of the techniques I’d used on a book I wrote, with Michael Lang, on the Woodstock music festival. Everybody knows Woodstock. I tried to tell the back story, go deep, and show all the things happening behind the scenes and turn something people think they know into a page-turner. You know, what’s going to happen next? So that even those people who are experts on the music or knew Alex, they can get sucked into the whole story and taken on a ride … this crazy ride that Alex had with his life.

But I was hesitant about coming up with an “agenda” based on what I learned about Alex, because there were many Alexes. I think he’s inscrutable in many ways. Anyone looking at him as a one-dimensional person would be mistaken. I wanted to show how multifaceted he was, shed as much light as I could on some of the decisions he made, why he made them musically or whatever. You can see that when you understand his life and the music in his life, the tragedies in his life.

I had no idea, for example, about his family history. He confided in friends about his brother Reid’s death. I didn’t have that close a relationship with Alex. Fortunately, friends shared things with me, and I feel very, very grateful that people trusted me with information Alex had shared with them.

Alex’s only living sibling, his sister Cecelia, lives in Memphis. She’s a terrific person, loves music, is involved in folk music. Yes, I interviewed her. Family friends I got to meet were a big help too. But Alex’s wife Laura chose not to participate in the book, and his son Timothee is in prison in Oklahoma. I didn’t contact him. My focus was on the music. (Timothee did turn his dad onto “Boogie Shoes” by K.C. & the Sunshine Band!) Sadly, I don’t think Timothee got to spend much time with his father.

True to say that Alex Chilton reached some peace in his later life — married a second time, happier touring and performing, happier simply making music?

The last I spent with Alex was in 2004. The year he died, 2010, I didn’t have one-on-one time with him, but he was in a good place when I spoke with him last, though he was having some health problems even then. He was in a good mood. He was happy. When he met Laura, I think he became fulfilled in his personal life, and everyone I spoke to, who got to spend time with him in the last couple of years of his life, they all remarked on that.

But, you know, he was a temperamental person. He was never going to be like some lobotomized happy guy. He could have bad days, but compared to earlier periods of his life, he was in good place.

And what of the man’s music, his legacy?

Alex had such a mystique about him, a charisma. As a musician, he was so diverse, he did so many different kinds of music. He had really catholic tastes. He was also very picky. But given all these genres he pursued … you don’t get tired of him. He was no Johnny-one-note. Even the three Big Star albums are different from one another.

We also haven’t heard his music to death. And people love to discover something, delve into it, find the buried treasures. Even Alex’s voice … talk about multi-textured.

And still, when I’m driving around … there’s a cool oldies station here in the Catskills. They play a lot of Box Tops, and whenever a Box Tops song comes on, I crank it up. I never get tired of any of Alex’s music. I love it all. The bootleg live shows … the incredible songs Alex dug out.

I hate to sound maudlin, but I have to tell you. My son Jack got to meet Alex, who gave him some Mardi Gras beads when Jack was only 8 weeks old. Jack is now 16. His birthday in January … my house was full of teenagers running around, and at the end of the party, there were about 15 kids left, clustered in the parlor of my house.

All of a sudden I say to myself: I recognize that music! I go running in, and one of the kids had an acoustic guitar. These boys and girls were sitting there, playing and singing “Thirteen.” I thought, That song really speaks to them — in 2014. You think about all the music kids today have at their fingertips, and this song, written by Alex in New York City in 1970 or ’71, it still speaks to them. There’s something poetic in that. •

For more on Holly George-Warren’s appearance on Wednesday, April 2nd, at Crosstown Arts — which will include a conversation with Andria Lisle, a book-signing organized by the Booksellers at Laurelwood, and live music by Ross Johnson, the Klitz, and Loveland Duren — go to crosstown arts.org. Doors open at 6 p.m.; author Q&A at 7 p.m.