For some decades, the medical world — and those lay people whose destinies brought them in contact with it sadly, apropos potential responses to cancer — has been acquainted with a phenomenon called HeLa cells.

These were malignant cells — used for research and medical experimentation the world over — that derived originally from a single tumor that had belonged to a patient whose name was believed to have been Helen Lane.

The cells were unusually virulent — so much so as to serve so distinct and widespread a purpose. Indeed, they were, and are, regarded as immortal, and by now have been cultivated and dispersed so widely for so many different purposes as to weigh, by informal estimate, the equivalent of 150 Empire State Buildings.

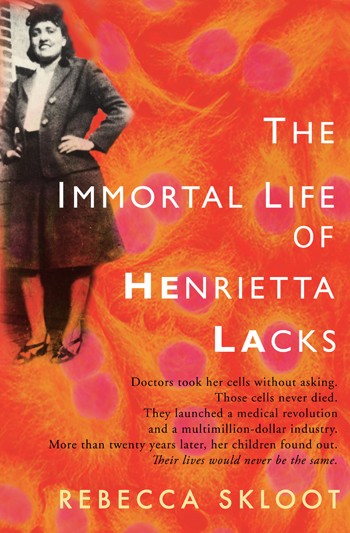

So far the story is interesting, even uniquely so. But it gets more so, in numerous ways. In 2010, an author/researcher named Rebecca Skloot published a book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, that transformed the way in which both the ubiqutous HeLa cells and the supposed “Helen Lane” herself were regarded.

Skloot was in Memphis this week as the featured speaker of the Memphis Rotary Club’s regular Tuesday luncheon — which this week was also a climactic focus of a “big club” national Rotary conference for which the Memphis club served as host. The conference began Sunday night at The Peabody with a spirited keynote address to the attendees by Dick Enberg, the well-known sports broadcaster.

Skloot, though, was the piece de resistance. Reminding those attendees who had read her book and explaining to those who hadn’t, she noted the first basic fact — that the soap-opera-sounding “Helen Lane” was a figment of some researcher’s imagination. The actual — unintentional — donor of the HeLa cells was one Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman from an impoverished family in Maryland who developed cervical cancer and was admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore as a charity patient.

The dime-sized tumor that was extracted from Lacks was a godsend to medicine. HeLa cells were vital not only in cancer research but in numerous other medical breakthroughs, including the development of early polio vaccines. But as Skloot documents, the saga of Henrietta Lacks (who died within six months of initial treatment) had analogues to more sordid medical researches — like that of the African-American syphilis patients in Tuskegee, Alabama, some of whom were purposely infected with syphilis, and all of whom were allowed to die without treatment while the progress of their disease was tracked.

Nothing that graphic happened in the case of Henrietta Lacks. Nor did such malpractive affect the members of her family, who subsequently also become medical subjects. Eventually — thanks in part to the efforts of Skloot, who now runs a foundation to benefit unwitting former subjects of medical experimentation — a protocol has been accepted in medical circles that expands the rights of such patients and has firmed up the concept of patient consent.

But ethical questions remain, and, considering the astounding number of ways in which medical samples are routinely collected from all of us, it remains true, as Skloot reminded the Rotarian conferees, that “in some way, everyone is a potential Henrietta Lacks.”