City Council Chair Berlin Boyd has described UrbanArt as a “quasi governmental” and failed organization. It’s a harsh, and not entirely accurate, assessment of a 20-year-old independently managed not-for-profit group that made Memphis a “percent for art” city, transforming the landscape and public expectations in ways that can only be understood by juxtaposing what was with what is now so ubiquitous it’s easily taken for granted.

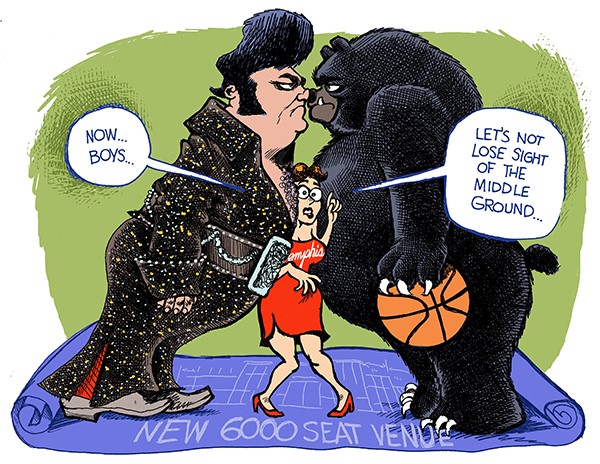

Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens

Twenty years ago, public art in Memphis meant statues. More specifically, it meant bronze statues of “great men” like slave trader and KKK leader Nathan Bedford Forrest and Confederate President Jefferson Davis. There were other, not entirely regrettable examples, of course. Elvis Presley and W.C. Handy were both immortalized on Beale Street. Overton Park had its Doughboy, and the downtown waterfront had an obelisk dedicated to the selfless heroism of Tom Lee, “a worthy negro.” There were even a couple of modern works isolated on the North end of an entirely desolate Main Street mall, hidden from a majority of Memphians who’d been fleeing the decaying urban core for decades. But once you accounted for the musicians, heroes, war memorials, and idols to white supremacy, there wasn’t much else to brag about. Today, by comparison, a drive down James Road includes painter Jeffrey Unthank’s impressive, epically scaled history of Frayser. A visit to Overton Square brings drinkers, diners, and shoppers into contact with multimedia artist Kong Wee Pang’s sparkling bird mural and sculptures by Yvonne Bobo, in addition to all the actors and musicians populating Memphis’ once-empty, now-prospering music and theater district. The Benjamin L. Hooks branch of Memphis’ public library is an enchanted forest of ideas. Kindergarten students entering Downtown Elementary are greeted by Lurlynn Franklyn’s fine mosaic floor. These are just a few examples of what a “failed” organization has accomplished in two decades. The successful revitalization of abandoned neighborhoods like South Main, Broad, and Crosstown, are almost impossible to imagine uncoupled from the influence of UrbanArt and work by local, regional, and international artists.

UrbanArt, which is funded in part by ArtsMemphis, the Tennessee Arts Commission, and by private donations, developed Memphis’ Percent for Art program with a complete awareness of just how easy it has always been for politicians to look serious and frugal by cutting apparent luxuries like art. That’s why percent for art funding was tied to a mere 1 percent of money already budgeted for capital improvements — money that would have been spent anyway, and without the transparency, community access, and public monitoring UrbanArt already brings to the table. Whether or not one loves every piece of public art that gets installed, the organization has repeatedly made its motivating point that artists are creative problem solvers and that makes public art a tremendous bargain.

In every case, public art requires political will because everybody’s a critic. And, to give Boyd his due, more can always be done to create opportunities for local and minority artists while hedging against provincialism and cultivating a healthy mix of national and international influences. But in a relatively short amount of time UrbanArt has made Memphis better. That’s no fail.