Imagine living in a country where a minority group that comprised a mere 6 percent of the population was in complete control. A country where a full 94 percent of the populace had no say whatsoever in their own governance. Does this sound like some future dystopian version of America, given our present trajectory? Sorry. This was the political reality of America at the time of the first presidential election in 1789.

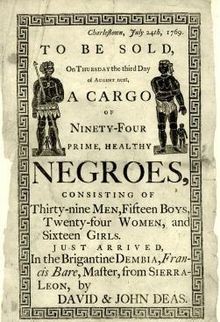

Many of those who signed our Declaration of Independence would have argued that the phrase “all men are created equal” only referred to land-owning Christian white males. At the time, the Colonists were still bound to that lowest form of oligarchical governance, the monarchy. The above statement was not penned as an enlightened declaration of inclusion, but solely to invoke a political break from that monarchy.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

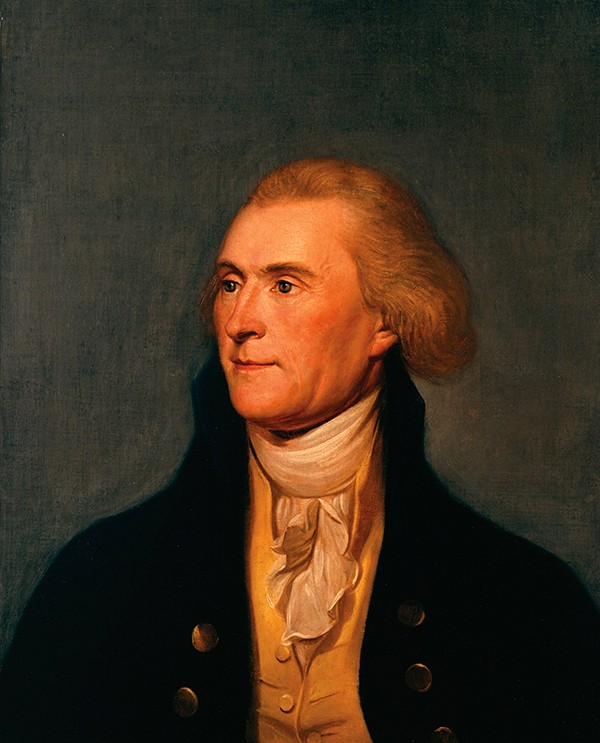

Thomas Jefferson

Thankfully, Thomas Jefferson, though himself a slave owner, was also a student of the Enlightenment. He understood that the prophetic words, however he had to spin them at the time, would eventually come to be taken more literally. Fifty years after the signing, Jefferson said of the Declaration: “May it be to the world the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government.”

At the time of the Revolution, free Americans were divided into two classes. You were either somebody, which almost exclusively meant being born into wealth and privilege, or you were nobody. And nobodies, even white male nobodies, were not allowed to vote. Additionally, prior to 1828, some states’ “religious tests” required voters to be professed Protestants. The last vestige of the property ownership exclusion was not abolished until 1856. Even then, some states continued to disallow non-taxpaying citizens the vote for another half-century.

The Fourteenth Amendment of 1868 opened the voting booth to naturalized, non-native-born citizens. Although the Fifteenth Amendment extended the right to vote to former male slaves in 1870, most Southern states — Tennessee being foremost among them — concocted such Jim Crow-era stumbling blocks as poll taxes and literacy tests that persisted until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Women, regardless of race or status, could not vote prior to ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. The final expansion of American voter eligibility did not occur until 1970, when the minimum voting age was lowered from 21 to 18.

Now try to imagine living in a country where only 43 percent of the population was in control. Even after all of our incredible progress in the ensuing 227 years since the first presidential election, that’s the percentage of the total population who voted in 2016. Certainly an improvement, but still hardly representative.

So here we are, 20 years into the 21st century, and still we have to ask ourselves to what degree do “ignorance and superstition” continue to rule our lives? Although Tennessee ranks 14th in the nation in terms of our number of eligible voters, we are 49th when it comes to actual voter turnout. In 2016, 2.4 million Tennesseans stayed home and did nothing, which is not only inexcusable, but unacceptable. The next time anyone tries to convince you that Tennessee can’t be “flipped,” consider the fact that nearly twice as many of our people failed to uphold their civic duty as voted for Trump in 2016.

As we continue to transform into a more enlightened and egalitarian nation, the pace of this effort will be wholly dependent upon the action, or inaction, of every eligible voter. We can only “assume the blessings and security of self-government” when every person who can legally vote, votes. Without question, 2020 will be the single most significant election since 1860 — the election that was immediately followed by the bloodiest decade in American history. And the outcome could very well be determined by those who, in the past, for whatever reason, have chosen not to participate.

If you care about your country, if you care about preserving democracy for future generations, your job this election is not only to vote, but to motivate every other citizen who sat out 2016, especially those who would not have had the right to vote in 1789, to vote in 2020 like their lives depended on it.

Voter registration deadline is October 5th. Early Voting is October 14th through October 29th. Last day to request an absentee ballot is October 27th. The election is November 3rd.

Aaron James is a seventh generation Tennessean, retired architect (Texas and New York), self-published author, and Independent Centrist candidate for U.S. Senate.