Spinach, the meatiest of vegetables, is finally in season. The fleshy leaves of spring spinach are juicy with a potent green serum that’s high in iron and exceptionally rich in chlorophyll, which is a close chemical relative to hemoglobin, the red stuff in blood.

This time of year, spinach is so abundant one can cook with it by the handful. Spring spinach comes in waves, the first of which was planted last summer as a fall crop and coaxed through the winter under a blanket of snow. In spring, the overwintered spinach rages to life, with leaves that are as sweet as they are lusty.

These leaves grew from roots that were well-established last fall, as opposed to the second wave of spinach, planted months ago in greenhouses. It’s about the same size as the overwintered spinach, but lacks the experience and terroir of the elder plants, which have had more time to accumulate nutrients.

Young spinach, including the so-called baby spinach that’s all the rage, is very convenient. It barely needs washing or any form of prep and is as tender as veal. It may not have the sweetness of an overwintered spinach, but neither does it have the bitterness.

The final wave of springtime spinach hits right before solstice, when the field spinach gets big and leafy. It won’t be as sweet as overwintered spinach, but it will be just as meaty.

Assuming you have the good stuff, then, what to do?

If you can get the good stuff, the overwintered green crème, then I’d recommend a very simple pesto with nothing more than spinach, olive oil, and salt. This is a spectacular way to enjoy the subtle complexity of an overwintered spinach. Like a vegetal blood transfusion in your mouth.

The leaves of springtime spinach clean easily. A blemish on a leaf can be tolerated in pesto, the sausage of plant foods.

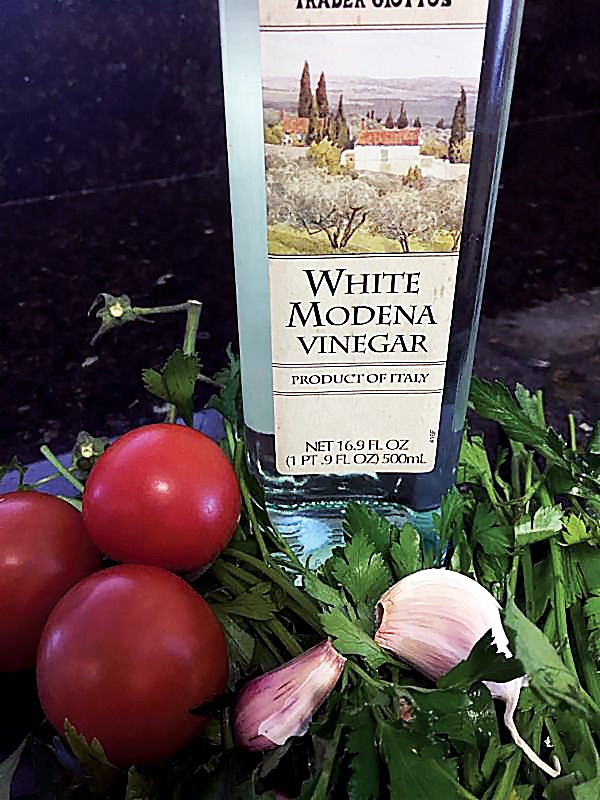

If your spinach is good but not quite top level, a more typical pesto with nuts, cheese, garlic, and zest will be a very satisfying way to enjoy the season. I’ve also had great results by simply combining fresh spinach pesto au natural with year-old basil pesto from the freezer.

The next recipe comes by way of Bhutan, a little Buddhist country in the Himalayas, where chile is king and cheese is queen and all other foods are cooked in a combination thereof.

Bhutanese spinach with chile and cheese

1-3 ounce dried red chile

four handfuls of spinach

½ to 1 cup Mexican cheese blend (or ¼ – ½ cup feta)

salt (unless using feta)

water or stock

cooking oil

First, get the chile soaking. Rip out the stem ends of the pods, tearing off the good bits of flesh and discarding the stems, inner seed heads, and as many seeds as you wish for the desired heat level. Tear up the leathery walls of the chile pods or leave them intact, depending on how avoidable you want the pepper pieces to be. Cover with water and soak.

Meanwhile, mince a medium-sized onion, and sauté it in olive oil and maybe a little butter. Add the half-soaked chile, and allow to cook, covered, with the onions. After about five minutes on medium heat, add two or three handfuls of spinach — as many as you can fit in the pan — in whole leaf form. If things are on the dry side, add water or stock, a half-cup at a time, until the pan bubbles with deliciousness. Cover.

After about five minutes, the spinach will have cooked down. Add more spinach if you can push it in, ideally another handful or two, and then add the cheese — ½ to 1 cup of Mexican blend, depending on how big your cheese tooth is. Some Bhutanese expats will occasionally use feta — if so, mind the salt. Cover again for about five minutes, then stir until all the cheese has melted into the sauce.

Add more water or stock as necessary so it doesn’t dry out. If the cheese burns it will be a chewy, lumpy mess; but if the pan is properly hydrated, the cheese will dissolve into a luxurious gravy. Add salt to taste, and serve with jasmine or basmati rice — or better yet, Bhutanese red rice.

Ari LeVaux

Ari LeVaux

Og-vision | Dreamstime.com

Og-vision | Dreamstime.com  John Lee

John Lee  Tom Moertel

Tom Moertel

Ari LeVaux

Ari LeVaux