Shot mostly around Wapanocca Lake in the Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge near the town of Turrell, Arkansas, Saj Crone’s exhibition of photographs, “Sylvan Joy,” examines the mystical essence of Southern swamplands. The show is dedicated to Crone’s friend Lewis Guest, who introduced her to the area’s arresting landscapes. The opening shot of Guest walking out into nature with his back to the camera is a thoughtful touch.

Crone is capable of defining innumerable thin layers in thick swamps of bald cypress and water tupelo. She deftly explores the significance of the surrounding waters, particularly in photos of Greenbelt Park, the very front yard of Memphis. The proud trees on the banks of the Mississippi stand immovable, looming over flood waters and crisp, white snow alike. Her use of reflective lines is well thought out, adding clarity to each circumstance in either soft ripples or crystal-clear parallels.

There is a profound understanding and respect for the order of undisturbed nature in “Sylvan Joy.” One shot of Wapanocca in particular captures large tree bases and dry undergrowth that form to closely resemble a small village of cozy huts, reminding viewers of nature’s role in the affirmation of all humanity.

The last two lines of David Wagoner’s poem “Lost” are especially poignant as a source of inspiration to the exhibition: “You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows where you are. You must let it find you.”

Through December 9th at the Beverly and Sam Ross Gallery,

Christian Brothers University

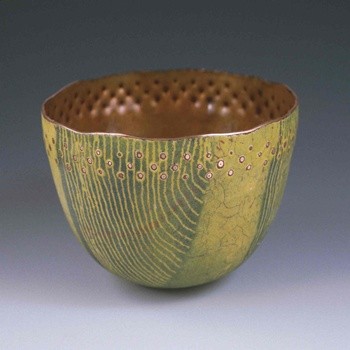

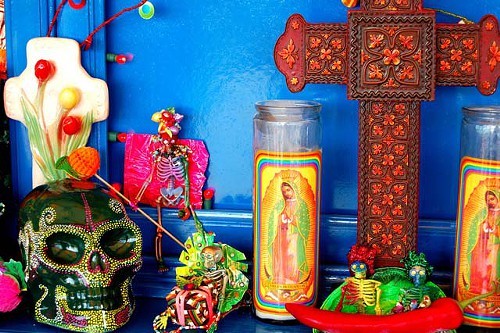

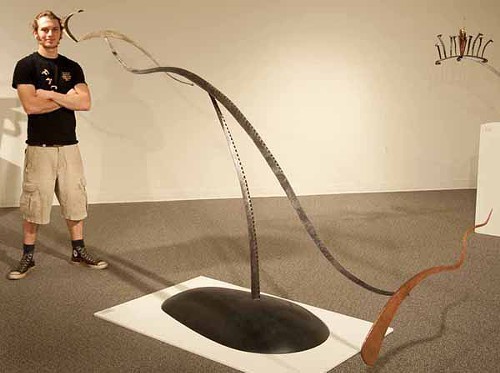

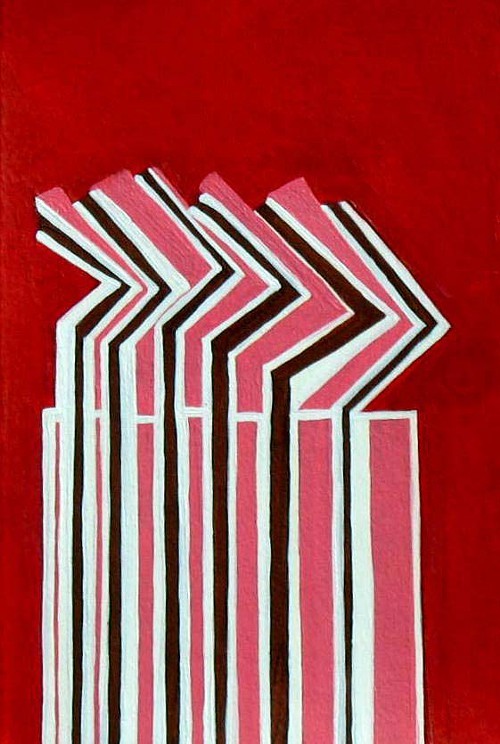

Cara Tomlinson’s exhibition “One to Other” at Rhodes College blends carefully strewn sculptural pieces with paintings to transform the Clough-Hanson Gallery into a subtly altered reality.

“I see my work as being in the tradition of abstraction. I generally call it ‘symbolic abstraction,'” Tomlinson says.

Her paintings possess a sense of building and blossoming that carries over to her sculptures — messy paint palettes that grow organically to form little blocks and gentle mounds, almost resembling stools. The effect is altogether unique, as though unseen guests are meant to occupy this space, further drawing the viewer in.

Tomlinson displays a mastery of color and absolute expertise in the realm of oil on linen, mixing bits of brightness with the greater muted content that takes up the majority of each canvas. Tomlinson’s sundry influences include Braque, the Surrealists, Paul Klee, and Philip Guston, as well as the studies of cognitive science, psychology, and anthropology.

Through December 7th at Clough-Hanson Gallery

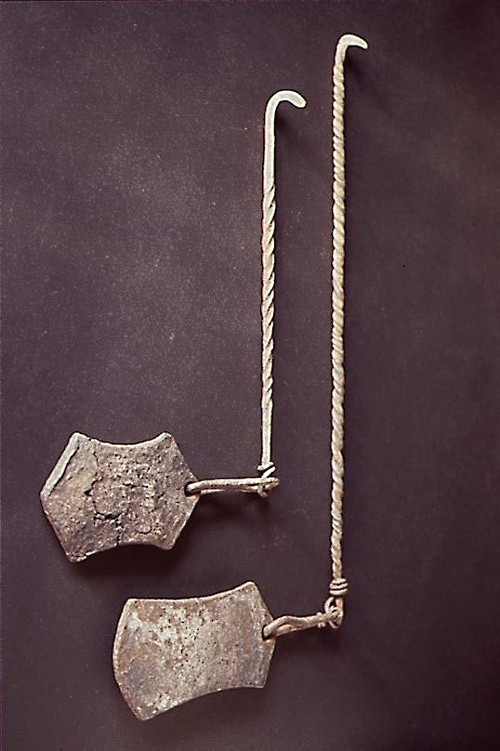

From the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, “Armed and Dangerous: Art of the Arsenal,” now showing at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, pulls together weaponry from around the globe to demonstrate how even some of the world’s most menacing objects can also be dramatic works of art.

An important historical concept behind the exhibition is to look at how human weapons reference nature and animals.

“We wanted to give our visitors a full concept of armor as something that was invented by nature long before humans came along,” says Marina Pacini, chief curator at the Brooks.

In some cases, this involves actual animal parts integrated into the overall design of weaponry. In other cases, elaborate depictions and even figurines looped into the base of a samurai sword demonstrate the presence of natural influences. Impeccable craftsmanship and delicate decoration of every lethal crossbow, sword, and pistol are impossible to overlook and differ vastly according to the weapon’s origin.

The suits of armor are especially noteworthy as they draw distinctions between different cultural traditions. While Western armor was remarkably restrictive, the battle gear suited to Japanese samurai was substantially lighter with a much greater range of mobility, due primarily to the island’s warmer climate.

“It makes a really interesting contrast. Apparently, the Japanese developed full-body armor before Europe did, because originally, the Europeans thought anything other than a shield was the sign of a lack of bravery,” Pacini says.

Much of the exhibition conveys an attempt to intimidate opponents. One central characteristic of classic combat helmets throughout history was to mask every part of the face except for the eyes.

“It’s a sense of erasing your humanity to make yourself look more threatening, more terrifying to your opponent,” Pacini says.

The Brooks hopes to draw new blood with such unintentionally artistic endeavors. An audio tour of the exhibit is available for visitors to use on iPhones by downloading the Brooks app or on one of several iPod touches the museum has handy. An interactive room for all ages — complete with a wearable samurai suit and camouflage wall — will be open for the duration of the exhibition.

Through March 11th at the Brooks

One last thing … the Flyer‘s longtime art reviewer Carol Knowles has moved to Portland, Oregon. We thank her for all her hard work and wish her well on her new adventure.