Pulling up to El Gallo Giro on Lamar Avenue, I hurried behind my mom as she grabbed a handful of volantes from the car and walked into the restaurant. She asked the manager if she could pass them around, and a second later she was introducing herself to everyone, one by one, and handing them a flyer.

Some entertained a conversation. Others received a flyer and continued eating, and my mother moved on to the next person. I don’t remember what was on those flyers, probably some kind of community event. But it wasn’t the flyers that left an impression on me. It was watching my mom move through the room and approach each individual with a paper in hand and a smile on her face. I stood a few steps behind her as she made her rounds, watching in amazement. The conversations were brief but personal.

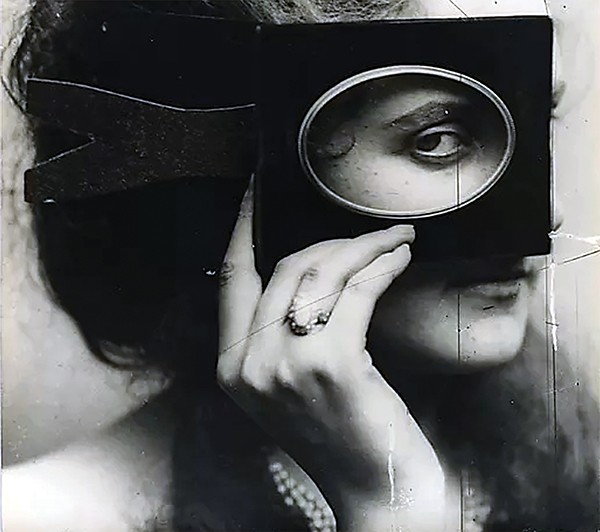

Tmcphotos | Dreamstime.com

Tmcphotos | Dreamstime.com

Can’t you hear me knocking?

My reaction to this also left an impression on my mom. When she shares this story, she laughs as she recalls, “Me preguntastes, Mamá, ¿cómo hablas con extraños?” How do you speak to complete strangers like that? I was about 7 years old then. I couldn’t recall anything in school that would prepare me to do something like what she had just done. In a society where we’re supposed to watch out for ourselves and our family, Mom was bringing in the community around her. She wasn’t talking at people, she was listening and connecting people to each other.

That was one of my earliest memories of seeing “ground game,” as political campaigns call it, in action.

Last week, I was driving back into the city when I was reminded of this moment. My Spotify-curated playlist “Your Top Songs 2016” played in the car, and I was driving through Jackson when Bambu started rapping about the ground game. Bambu is a father, organizer, and Filipino American hip-hop artist from L.A., and, like my mom, he’s not shying away from having one-on-one conversations with his neighbors. “That’s the beginning of groundwork / Building on that face to face / And not just on that Facebook, organizing on a Twitter page.”

Bambu ain’t wrong.

As technology and social media advance, it’s easy to lean too much into those tools. The primaries are getting here closer and closer (early voting in Tennessee starts on February 12th). We cannot rely on social media to do the work for us. The posts, shares, and retweets may be good at distributing some information, but they’re not enough to activate the change we need.

Campaigns know this, too. Having a strong ground game, having conversations with people directly, is the most effective way to turn out voters, and you can learn a lot about a campaign that is investing in this work.

To some, knocking on doors or making cold calls to voters isn’t the most exciting part of activism. It may even seem daunting. But we have to think of it as a muscle we’re exercising. You’re not going to knock out a marathon tomorrow morning without any training or preparation. You have to practice, run a couple of races; you’ll make mistakes, and you’ll get better. It’s similar to having a conversation with someone in the context of furthering a movement or political campaign forward. You’ll get people who are on board with you and others who will disagree. No one expects you to have all the answers — just to be a part of something larger than yourself.

Social media protects us a bit in this way. We sit comfortably behind our screens, away from confrontation or rejection, but without having real conversations with our friends, family, and neighbors, we’ll continue to be in a cycle of reacting to news, logging off, and not doing anything to change it. Getting active in your community and learning about and supporting other communities can be enjoyable and healing. Don’t just stick around when it’s fun and convenient. Lend a hand because when you need it, your community will be there for you.

We need you now. Our city needs you now. So put on your walking shoes, and let’s talk to our neighbors.

Aylen Mercado is a brown, queer, Latinx chingona and Memphian exploring race and ethnicity in the changing U.S. South.

Mikalai Bachkou | Dreamstime.com

Mikalai Bachkou | Dreamstime.com  Mkopka | Dreamstime.com

Mkopka | Dreamstime.com  Calvin L. Leake | Dreamstime.com

Calvin L. Leake | Dreamstime.com  Jitdreamstime | Dreamstime.com

Jitdreamstime | Dreamstime.com

CNN Video

CNN Video

BertaCaceres.org

BertaCaceres.org