While there is some disagreement on the time period, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce defines Generation Z as those born after 2000. In four years, the first batch of these Y2K babies will be early-onset adults, members of the freshman collegiate class of 2018, voters, and, in some cases, job-seekers. They are us the day after tomorrow.

So who are they? What are the influences that have shaped their worldviews and personal perceptions?

GenZ-ers’ lives began with the “hanging chad” and the contested 2000 election, in which a month-long political battle over who would be the 43rd president was decided by a controversial Supreme Court ruling in George W. Bush’s favor. Their innocence was lost by their first birthday, as the United States and the world were rocked by the terrorist attacks of 9/11. With the invasion of Afghanistan and the toppling of Iraq, Generation Z has known nothing but terror and a war on terror.

Z-ers have also witnessed the violence of nature. An outbreak of the respiratory disease SARS decimated hundreds in Asia and started to spread across the globe. A mega-tsunami killed hundreds of thousands living near the Indian Ocean. A Japanese tsunami destroyed a nuclear power plant and radiated the Pacific Ocean. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated New Orleans and many cities along the Gulf Coast. Heck, even Pluto lost its status as a planet.

As Generation Z was entering second grade, the “Great Recession” shook the foundation of the global economy, weakening fiscal systems and wrecking individual savings. As a result, many Z-ers experienced poverty or watched friends and family members struggle financially.

Gen. Z witnessed history as the first African-American president won the 2008 election. The brief Democratic super-majority in the Congress and Senate fought the recession with a stimulus package and passed the Affordable Care Act — thereby igniting a fury of political partisanship which gave birth to the Tea Party.

Generation Z’s middle-school years saw the congressional repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in the military, as well as the Supreme Court ruling against the Defense of Marriage Act, which opened the door to same-sex marriages in many states. The tweet became mightier than the sword, as an “Arab Spring” of revolts and civil wars spread across the Middle East. Osama bin Laden was killed by American Special Forces.

Our hearts were broken by mass shootings in Aurora, Colorado, and Newtown, Connecticut. The Boston Marathon was bombed, and the country stood strong with the Red Sox Nation as they won the 2013 World Series.

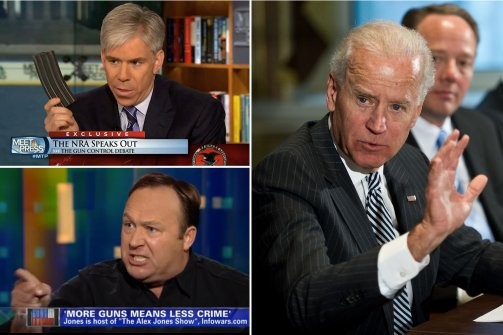

Gen. Z’s first wave are now freshmen in high school, living with constant, swirling political vitriol. President Obama’s second term has been plagued by Republican investigations into the terrorist attack in Benghazi, Libya, the alleged targeting of conservatives by the IRS, and the revelation that the NSA was mass-collecting American’s cell phone records. Unbridled political partisanship and uncompromising ideologies are the governmental models they are witnessing.

These natives of a digitalized world have primarily experienced these dramatic events through some form of technology. An analog existence seems like the dark ages. The concept of collecting music or movies in physical form seems medieval to them. The majority of Gen. Z-ers have never invited someone over to see their record, tape, or CD collections. Their lives have been immersed in social media.

Generation Z’s use of the open-source reference site Wikipedia, founded in 2001, contributed to the death of the printed version of the 244-year-old Encyclopedia Britannica. That same year, Steve Jobs handed the CD a death sentence with Apple’s personalized digital music player, the iPod. Professional and social networking started to bloom in 2003, with MySpace and LinkedIn. Facebook and the picture-sharing network Flickr entered the scene in 2004.

In 2005, YouTube began providing videos that could be instantly shared. In 2006, the first 140-character communications were transmitted on Twitter. The 2007 2G iPhone transformed the mobile phone market and was followed by the iPad tablet in 2010. Generation Z has not known a world without the internet. Their globalized networks, virtually unlimited connectivity, and ability to multi-task between devices, gives GenZ-ers a skill set unlike any generation before them.

Generation Z-ers follow us, but they will ultimately be leading us. In four short years, these digital natives will be invading our offices, ballot boxes, and universities. Are we ready for Generation Z? We’d better be — and for whatever letter of the alphabet or mutation in Outlook — comes next.

(Brandon Goldsmith, a frequent Flyer contributor, is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Communication at the University of Memphis. This piece is adapted from a portion of his dissertaton)