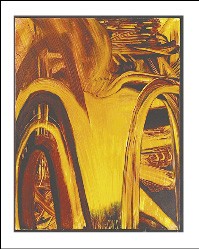

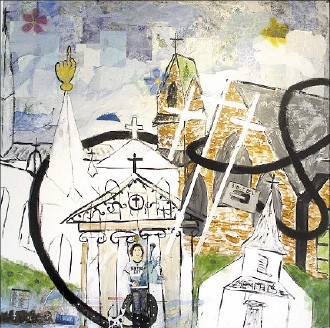

Many of the paintings in “Vacate Now!” Bobby Spillman’s exhibition at L Ross Gallery, roil with energy. Fires flash, lightning bolts, and toy airplanes blast across the surface of his canvases.

Against the Wind, one of the show’s strongest works, is a rush of emotion and energy. The day after several tornadoes roared across the Mid-South and his father had a heart attack, Spillman loaded a brush with white, yellow, and pink oils. In one spontaneous, continuous gesture he swirled the paint diagonally across 72-by-66 inches of canvas and created a multi-hued whirlwind.

In the complex feat of design Vacate Now, Spillman simulates psychic space. Light-blue bubbles percolate through layers of earth-toned speech balloons. Green volts of electricity and orange and fuchsia accent the artist’s daydreams and internal dialogues.

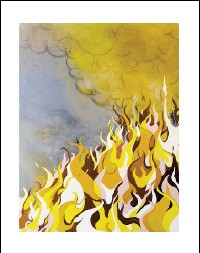

Spillman can handle subtly modulated hues and shapes as well as blocks of color and blasts of energy. In a particularly beautiful passage in Daily Ritual, a blue-gray sky faintly mirrors billowing smoke and orange, red, and white-hot flames.

Daily Ritual by Bobby Spillman

“Bobby Spillman: Vacate Now!” at L Ross Gallery through September 30th

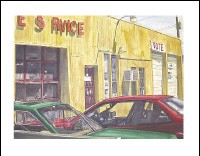

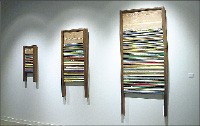

“Maysey Craddock: Unsaid,” at the David Lusk Gallery is, in large part, Craddock’s response to the devastation she witnessed in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Buildings and bridges stripped to their girders and broken and leafless trees are Craddock’s subjects. Her canvases are torn and wrinkled paper bags.

White Passage is one of the smallest, most crumpled works in the show and also one of the most beautiful. Its lacy bridgework, its maroon-umber atmosphere, and its surface (a paper sack torn apart and stitched back together with silk thread) speak of fragility, putrefaction, and the

White Passage by Maysey Craddock

patchwork repair of the Gulf Coast cities. For the installation The Memory of Your Words Never Leaves Me, the artist ripped the keys and typebars out of an antique typewriter, painted them dark red, and hung them from the ceiling.

Many of Craddock’s artworks in previous shows were nostalgic and delicate. In this exhibition, the artist gets to the heart and guts of things; she lets her ideas go wherever memory and raw emotion take her. With edgy, urgent work in “Unsaid,” Craddock says more than she ever has before.

“Maysey Craddock: Unsaid” at David Lusk Gallery through September 30th

For her exhibition, “A Glimpse of Motion” at Perry Nicole, Anne Davey looked down into the pale aquas of chlorinated swimming pools and the purple-umber shadows of lakes and recorded bodies moving in water. Her most accomplished works suggest multiple layers. In Glide, a small oil on canvas, sunlight dapples the surface of a lake. Just beneath, rippling water refracts brightly colored swimwear into an Art Nouveau mosaic of yellows and blues. Deeper still, bare limbs gliding through shadows in the lake kaleidoscope into peaches and umbers.

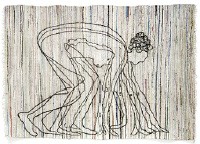

The body is reduced to undulating light and shadow backdropped by white gessoed paper in three charcoals, Underwater I, II, and III. These particularly subtle and assured works evoke dreamscape and mindscape and remind us that the world and everything in it are shifting fields of energy.

“Anne Davey: A Glimpse of Motion” at Perry Nicole Fine Art through October 1st

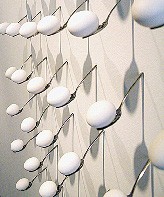

In “Amy Pleasant: You Are Here,” at Clough-Hanson, Pleasant builds worlds out of thousands of tiny ink blots, smudges, and miniscule figures. Her figures cluster like bacteria in Petri dishes. They spiral like stars in a galaxy, engage in mundane activities, and play out scenes from thousands of lives lived simultaneously.

In a haunting mosaic of overlapping shadows (detail from an untitled ink work on paper), a boy sits on the grass looking back at his house, a teenager stares into the sky, and a man pauses at a street corner. In another untitled paperwork, two tiny figures push and strain and enjoy a sexual encounter. To their left, a little boy sleeps with his teddy bear.

Mouse ears, bird wings, and a flurry of cat fur tell a story of death as well as life in a detail from Drip, a large ink work drawn directly onto the gallery walls. In another section of Drip, three tiny figures dive into the white wall. The several inches of space surrounding them look vast, but the tiny specks unhesitatingly embrace the cosmos. What courage and chutzpah. What an apt metaphor for life on earth.

“Amy Pleasant: You Are Here” at Clough-Hanson Gallery through October 11th