The Art Museum of the University of Memphis exhibition “Red Grooms: Selections from the Graphic Work” brings home the work of an internationally respected artist who grew up in Tennessee and spent much of his youth sketching people on the streets of Nashville. For the past 50 years, Grooms has lived in New York City, creating masterworks of humor, insight, and ingenuity not in bronze or on canvas but with torn paper, hot-glue guns, and printing presses.

“Red Grooms” was drawn from the collection of the artist’s lifelong friend, Nashville contractor Walter G. Knestrick, and the bulk of the exhibition’s 90 prints either immerses us in New York street life or in the lives of 19th- and 20th-century artists. Many of the show’s best works are cartoon-like lithographs whose saturate colors and exaggerated physiognomies reveal a physically and emotionally roiling sea of humanity.

Jackson in Action, a three-dimensional lithograph, features a nonstop Jackson Pollock. With a cigarette in the mouth of each of his two heads and his six arms slapping paint across a canvas, the artist ignores a turpentine can’s warning about flammability. In South Sea Sonata, another three-dimensional lithograph, Gauguin’s huge, brooding head tilts down, the eyes half-closed. He appears lost in imagination somewhere between his sketchbook and the Tahitian women who surround him.

In Little Italy (three-dimensional lithograph), Grooms takes us to the corner of Broome and Mulberry. We step into a New York neighborhood and look at life inside the apartments above a café and see the frustrated faces of drivers caught in traffic. Great attention to detail was given each vehicle, person, and building. For example, the iron grates of the fire escapes and the hair net of the woman people-watching from her second-floor apartment are die-cut from black arches paper. On the backside of Little Italy is a street in Chinatown created with the same care.

Other lithographs place us at Graceland, where Elvis‘ upper lip and hips angle as sharply as the skyscrapers that appear to sway with energy in Times Square, then it’s off to the fast-food stand of a New York Hot Dog Vendor, where they sell, what the artist has described as, arguably, the best hot dog in the world.

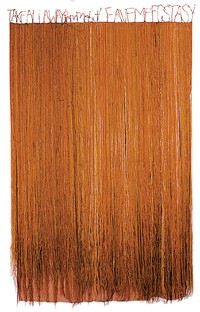

When Grooms explores 19th- and 20th-century masterworks, his own work becomes more insightful and inventive. In the atypical, nearly seven-foot woodcut, The Existentialist, the artist chiseled out the heavily lined, complex face of Alberto Giacometti, a sculptor who took art in unexpected directions. Alongside the weathered head are carved figures reminiscent of Giacometti’s attenuated, eroded works in clay and plaster.

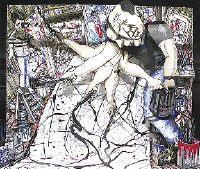

The three-dimensional lithograph De Kooning Breaks Through celebrates artistic freedom. It’s a faithful reproduction of Willem de Kooning’s 1953 work Woman and Bicycle, except in this version the wild-eyed, bubble-gum-pink, huge-breasted vixen (tramp, vampire, mother-from-hell) rides on the handlebars of the bicycle that de Kooning pedals through the center of the canvas. De Kooning Breaks Through pays homage to the in-your-face energy with which de Kooning defied modern art’s prohibitions against realism when he created his iconoclastic “Women Series.”

Fat Man Down evokes another culture. In this spray-painted stencil, two Sumo wrestlers push into one another with perfect equilibrium. They’re encompassed by a tiny red sun that floats in the center of 8-by-8-inches of untouched white paper. This image, an alternative version of Japan’s flag, is a resonant metaphor for the country — an island nation, land of the setting sun, pure Zen mind, Sumo wrestling, and haiku, 13 syllable poems that evoke fleeting images of nature.

Grooms is most compelling when he explores the full range of humanity. In his 1971 breakthrough lithograph Nervous City, rats as well as pedestrians scurry down a New York sidewalk densely packed with policemen, hippies, mothers with baby carriages, drug dealers, and pedophiles. The central figure, a street walker who is being drugged and sexually molested, stares directly at us with a maniacal expression.

Grooms’ depictions can be exaggerated and intense, but this wry artist is keenly aware of humankind’s foibles and tragicomedies. His presentation of passions that drive us to paint, to create the perfect hot dog, to destroy ourselves with drugs, to gain 400 pounds (so that we can knock down equally hefty opponents) gets it just about right.