In his half-century of creative output, Roy Lichtenstein produced

much more than the large-scale, comic-book inspired, eye-popping

paintings that brought him international fame in the 1960s. The nearly

70 drawings and collages that make up the Dixon Gallery & Gardens’

exhibition “Lichtenstein in Process” include ethereal Chinese

landscapes, fluid abstracts, and pop-art homages.

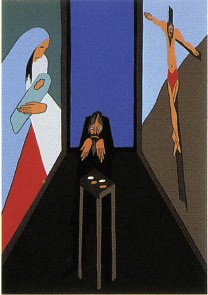

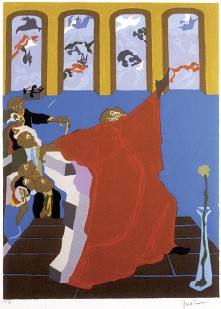

In Collage for Art Critic, Lichtenstein’s witty nod to

criticism as well as cubism, the critic stands with her nose pressed

against a painting and studies it from every angle. The features of her

face fracture into a Picasso-esque portrait in which her open mouth

moves to the side of her face, her left eye turns sideways, and her

other eye has moved to her forehead and pierces the frame of the

painting into which she peers.

Thousands of faint, nearly colorless Benday dots in Collage for

Landscape with Scholar’s Rock are transformed into veils of mist

and banks of clouds that appear to move, dissolve, and reappear across

a 7-foot-wide panorama that fills our field of vision. Stand in front

of Scholar’s Rock and, like the art critic, you may feel the

planes of the earth shift and boundaries blur as you are encompassed by

the most monumental (and most effervescent) collage in the show.

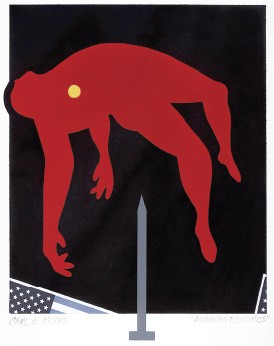

In another particularly powerful work, Collage for the Sower,

Lichtenstein pays homage to Vincent van Gogh’s 1888 painting which, in

turn, paid homage to Millet’s 1850 masterwork. Van Gogh’s brushstrokes

make his entire painting — sky and earth as well as the figure

striding across the landscape — come alive with energy. In

Lichtenstein’s work, the earth roils, seeds crack open, yellow melons

swirl across the top of the work, and spring-green sap oozes beyond the

thick, quickly gestured outlines of the figure. Lichtenstein captures

the sweep of the sower’s arm, the social unrest rumbling toward

revolution as peasants starve, and the boundless energy of nature as

powerfully as van Gogh’s and Millet’s more realistic depictions.

Through January 17th

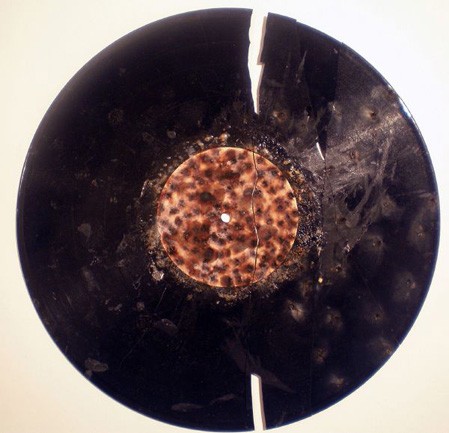

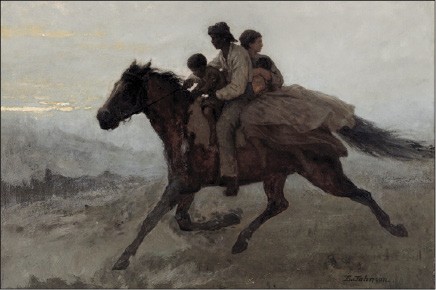

For each of the 10 photo

composites that make up Clough-Hanson’s current exhibition, “Riffs on

Real Time,” Leslie Hewitt places a snapshot — often faded and

decades-old — on top of a page torn from a textbook or on the

cover of the book itself. Hewitt then photographs the two items on the

wooden floor of her studio. What perhaps is most remarkable about this

understated show is Hewitt’s ability to evoke the whole fabric of life

with 10 artworks constructed from the simplest materials.

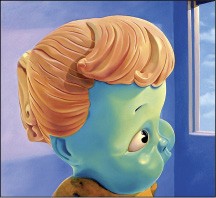

An out-of-focus snapshot of a shrub (so severely cropped it looks

more like a hat box than a plant) lies on top of bright-red book in

Riff 4. Riff 5 is the textbook image of row after row of

large, immaculately kept homes with perfectly manicured lawns. An

overexposed snapshot, laid on top of this image, looks like the living

room of one of the homes where family members watch television.

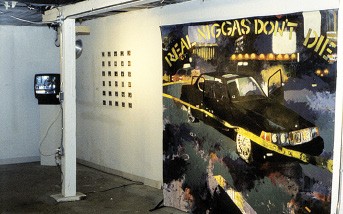

Hewitt mounts her most poignant and unsettling works in a small

room, a sort of inner sanctum, inside Clough-Hanson. The faded photo of

a young man in a cap and gown in Riff 2 is backdropped by

another textbook image of a city, but here, instead of suburban sprawl,

homes and businesses are blown apart and engulfed in flames. A man in a

suit in Riff 10 carries a briefcase and strides up the steps of

a beautiful concrete plaza of some large metropolis. In one of the

show’s most surreal touches, the man’s upper body is superimposed with

a snapshot of arid, undeveloped earth.

The images in Hewitt’s inner sanctum show us a world in flux.

Sometimes the change is slow but inexorable, like erosion. Sometimes

change is sudden and violent like the race riots depicted in Riff

2. In an interview mounted on one of the gallery walls, Hewitt

explains that the work for this show was developed, in part, to help

her understand how the civil rights struggles of the 1960s inform her

current view of reality.

How apropos that Hewitt’s “Riffs on Real Time” are backdropped by

the scarred, stained, rich-hued, and deeply grained heart pine floor of

her studio. This New York-based artist takes us beyond the pruned and

the concretized into a richer, more textured space where we are

encouraged to explore texts we never quite found the time to read, to

look through family photos and replay memories, to enlarge our sense of

self and the world.

(Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)

(Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)  (Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)

(Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery)