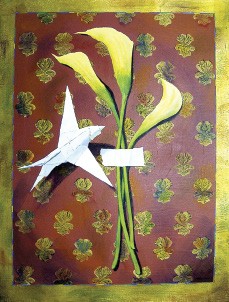

In her powerful mixed-media painting Red Crosses, currently

on view in the Jack Robinson Gallery group exhibition “Code,” Sam Red

blurs the boundary between the conscious and unconscious and between

the sacred and the profane. Across the surface of the painting,

Christian crosses drip blood. A series of circles looks more like worn

tires than symbols of perfection or eternity. A strip of brocade

wallpaper points to the top of the painting where the charred facade

and the crumbling archways of a villa or cathedral bring to mind

antique pontiffs’ hats or the soiled outfits of Ku Klux Klanners. This

is what ideology looks like in the real world.

Red Crosses reads, in part, like Francis Bacon’s mix of

religiosity and rot. Instead of being sardonic, however, Red’s

aesthetic sensibilities register as insistence that we look at the

world not as we wish it to be but as it is.

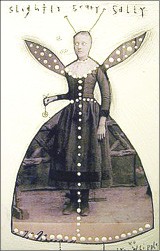

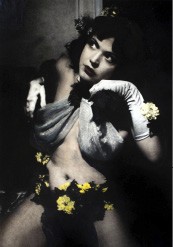

Years of chemotherapy that successfully treated photographer Tawnee

Cowan’s leukemia prevent the artist from taking medication to alleviate

the pain caused by an automobile injury. Cowan is able to forget her

pain, temporarily, when she photographs the fierce beauty and courage

of men and woman fighting cancer.

With fists clenched and mouth wide-open, the figure in Enough

rages against his fate. Some of Cowan’s subjects, like the Nashville

artist depicted in Enough, are winning the battle against

cancer. Others, more gravely ill, may not live to see Cowan’s book,

Warriors in Wings, to be published by the Wings Cancer

Foundation next year.

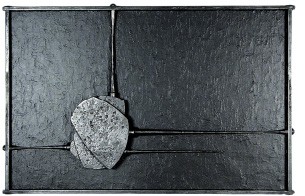

In Trapped Within the Unknown, one of Cowan’s most complete

statements regarding the human condition, a mosaic of delicate lines

crisscrosses her otherwise flawless porcelain torso and maps out a

network of nerves along which her back pain radiates. The title of this

work, the blindfold that Cowan wears, and the horizontal timber that

backdrops her head remind us that the cross that Cowan (and each of us)

bears is existential as well as physical.

Jennifer Barnett Hensel’s Lasting Conversation

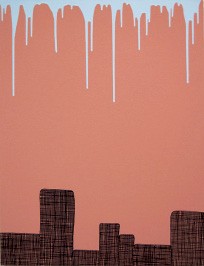

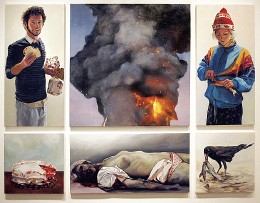

Some of Alex Paulus’ strongest paintings are stark, beautifully

drawn oil-and-graphite works with Bible verses for titles. Paintings

such as I Will Bring Locusts Into Your Country remind us of the

Old Testament emphasis on vengeance rather than compassion.

What looks like a high-tech pest exterminator is God’s instrument of

judgment in I Will Punish Your Country by Covering It With

Frogs. If piles of frogs are a barometer of God’s anger, we have

indeed aggravated the Almighty. Billions of frogs are going belly-up

worldwide, victims not of God’s wrath, however, but of pollution,

disease, and global warming. In an age of nuclear weapons, rapidly

depleting resources, and religious warfare, people as well as frogs

seem poised at the brink of destruction.

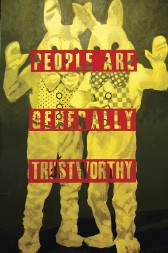

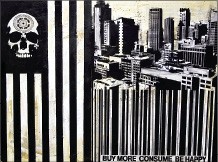

Paulus calls into question the ideologies of his time. Drawings of

studio lamps in Darkness suggest that the discerning eye of an

artist is enough to shed light on any matter — no blinding

visions, no celestial light required.

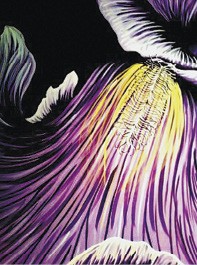

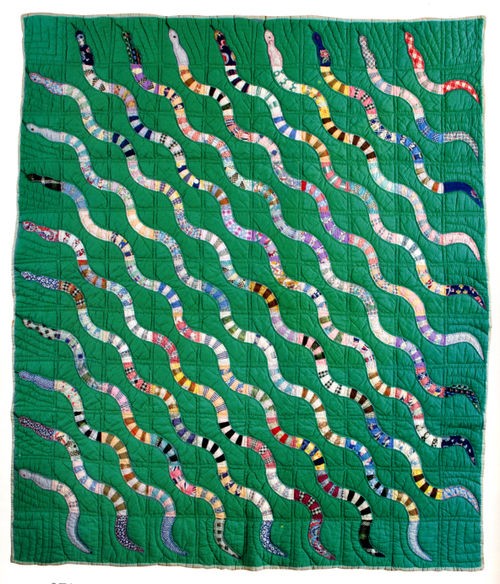

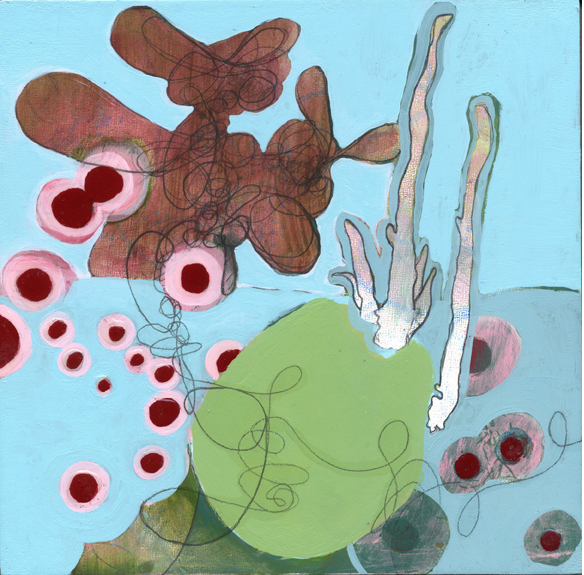

Jennifer Barnett Hensel takes contour drawing to the edge of chaos

— lines that loop into swarms of flies, a child blowing soap

bubbles, tentacles sprouting from biomorphs, blood corpusules floating

in a blue sea, and iron-rich earth morphing into rabbit ears and

phalluses.

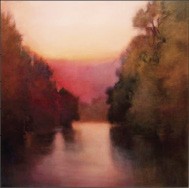

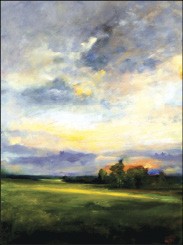

Barnett Hensel’s call-and-responses between the animal, vegetable,

and mineral worlds suggest a universal consciousness. Her strongest

paintings look like visual equivalents for lines from Dylan Thomas:

“The Force that through the Green Fuse Drives the Flower … blasts the

roots of trees … drives the water through the rocks … drives my red

blood.”