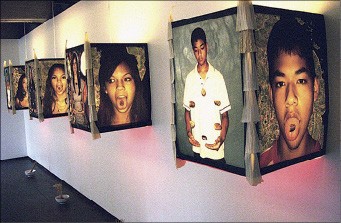

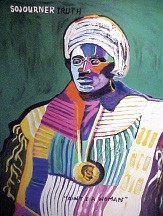

A group of self-taught Memphis artists, not well-known in their own city but revered by folk-art aficionados around the world, are featured in Memphis College of Art’s “Close to Home: African American Folk Art from Memphis Collectors.”

For Cross the Line, Edwin Jeffery chiseled the portrait of a muscular African American, his blond partner, and their daughter into a chunk of wood that looks like a large, clenched fist. A Klansman, with the empty, wide-eyed stare of mob violence, grips the man who has “dared to cross the color line” and forces his head into a noose.

Over the course of his life, Hawkins Bolden made hundreds of scarecrows out of pots, bedpans, and hubcaps drilled full of holes and held together with brooms, rubber hosing, pieces of frayed fabric, and whatever else “felt” right to the artist who was blind since childhood. Bolden’s deeply textured testaments to life conjure up bullet-riddled WWI helmets on top of old wooden crosses, 5th-century German warriors, fierce and starving, dressed in animal hides, and Don Quixote, battered shield in hand, fighting injustice on top of his broom-stick horse.

Gallery talk by University of Memphis art history professor Carol Crown at 5:30 p.m. and opening reception from 6 to 8 p.m., Friday, January 23rd, at MCA.

Through January 30th

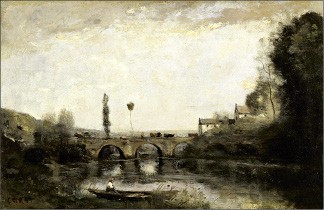

Jerry and Terry Lynn, identical-twin brothers working in tandem on the same canvases as Twin, reach a new level of mastery in their show “Recent Paintings” at David Lusk Gallery.

In The Ark, white jabs of paint scatter like doves above the heads of four slaves dressed in soft, white muslin and standing in a golden ark. Light, refracted in a pool of water, shatters the ark into countless gem-like facets. For Twin, the ark is not a thing to be coveted like the golden calf but a metaphor for vision and possibility.

Through January 31st

Hamlett Dobbins is an accomplished painter known for his textile-like surfaces that appear lit from within. His milestone work Untitled (Notes on Gu. K1.), part of his exhibition “Every One, Every Day” at the Dixon Gallery & Gardens, not only demonstrates his technical skill. It allows us to emotionally connect with an enigmatic artist who encrypts his titles and creates motifs so inventive they often evoke alternate worlds, in addition to the deeply moving moments from movies and life.

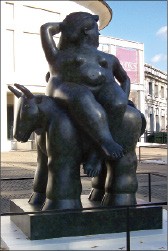

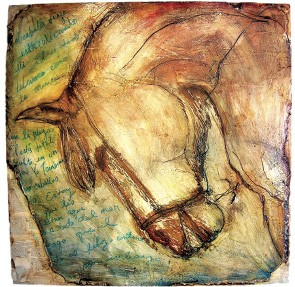

Mary Burrows’ Caballo Obscura at Perry Nicole

Striped, textured totems frame the edges of Untitled (Notes on Gu. K1.), but the body of the work is in flux. Golden-white light moves across the face of this canvas. Far below, gray-and-white washes float like clouds. Deeper still, golden-brown, soft-edged striations bring to mind the Legos Dobbins used as a boy to shape and reshape scenes from movies.

Instead of presenting us with a highly refined, crisp-edged simulation of one of his memories, Untitled (Notes on Gu. K1.) invites us into Dobbins’ process. There’s a fluidity, a largesse of spirit about this work that allows us to feel what moved the artist in the first place.

Through February 8th

For Perry Nicole Fine Art’s January exhibition, “ARTifacts,” gallery owners Nicole Haney and David Smith challenged their artists to “create a piece of work and provide with it an object of inspiration or tool used in its creation.” Instead of treating the challenge as an academic exercise, Haney’s and Smith’s artists dug deep.

In Susan Maakestad’s abstracted landscape Corral, pencil-thin outlines of railings course their way through washes of turquoise and coral. An orange pylon in front of her painting brings to mind slick interstates and what the artist describes as the “traffic cones, speed bumps, and crosswalks from which we take direction every day … but rarely examine.”

Mary Burrows mixes beauty with tragedy. In Caballo Obscura, pigmented encaustic becomes the silken fur of a horse in profile on a beach — its head bent toward the ground, its eye a blacked-out orb. Burrows scrawls the animal’s story across the background and mounts a braid of horse hair closeby. She not only pays homage to the horse’s power and grace but also identifies with a creature that, like this accomplished artist, has lost sight in one eye.

Through January 31st

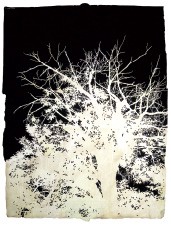

Edwin Jeffrey’s untitled scarecrow sculpture at Memphis College of Art