It’s 8 a.m. Saturday morning. Too early for gallery-hopping? Not if you love to mix java with artwork. We’re at Republic Coffee, and the walls are lined with some of the best paintings and photographs of Eric Swartz’ career.

In Dash, Swartz records the part of a vehicle we see as we slide into the driver’s seat. The rudimentary control panel inside this antique truck or sedan has become a rusted metal hulk. The windshield is clouded with algae and age. At the right edge of the image, a surprisingly intact steering wheel takes us back to mid-century when we were crisscrossing America’s brand-new interstates in the vehicles of our youth. Most of them are junkers now, metaphors for time and memory and a good jumping-off point for our exploration of the accomplished, richly symbolic artwork found in a wide variety of Memphis venues.

Through August 31st at Republic Coffee

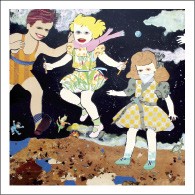

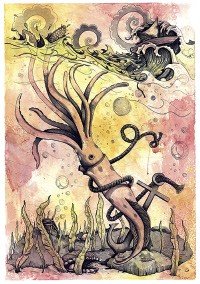

Our next stop is Material, the cutting-edge gallery that helped jump-start the now-burgeoning Broad Avenue Arts District. Niki Johnson’s and Melissa Farris’ exhibition “Moral Fiber” fills the small space with artworks charged with irony, intense emotion, and complex meaning. Nothing feels off-limits for these two sassy, savvy young artists who ask us to look into the face of power and sexuality, to question authority, and to challenge sexual taboos and the artificial distinctions between high and low art.

Johnson’s appliquéd portrait of a screaming Donald Trump, titled Old Yeller, asks us to consider whether we value cold corporate power more than the faithful companionship and courage typified by the stray dog in the American movie classic of the same title.

Viewers are encouraged to pull back curtains covering Farris’ shadow boxes. Inside are graceful, peach-and-pink watercolors of same-sex partners making love.

Many of Johnson’s and Farris’ artworks are charged with playful innuendo. Cupcakes, Johnson’s needlepointed studies of women’s breasts framed by fluted cupcake tins, are bite-sized and beautiful. Jonathan’s Quilt, Farris’ appliquéd portrait of a young man on an eight-pointed-star quilt with hand inside his jeans, transforms the “security blanket” into something we can hang onto from cradle to grave.

Through August 29th at Material

Gadsby Creson’s installation at the P&H Caf

Gadsby Creson’s installation at the P&H Caf

Just off Main Street, the walls of Power House Memphis are montaged with iPhone photos that internationally renowned contemporary artist Rob Pruitt took of Memphis. His most evocative work records Graceland’s 1960s décor and fans’ floral tributes to the man who revolutionized music, swiveled his hips, and helped thousands of youngsters come of age in the sexually repressive 1950s.

Pruitt’s images of an empty wheelchair imprinted with the word “Graceland” and a large statute of Christ resurrected on Presley’s gravesite most poignantly tell the story of the love affair between Elvis and his fans.

Through August 9th at Power House Memphis

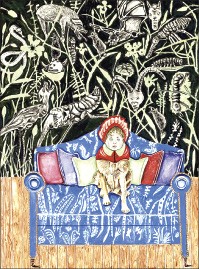

Several blocks farther north on South Main, we discover Micah Craven’s monotype Simple Food Simple Taste, one of the most powerful artworks currently on view anywhere in Memphis. It’s one of the prints in the group exhibition “Oh Lord, Won’t You Send Me a Sign!” at Memphis College of Art’s On the Street gallery. The show was curated by University of Mississippi chair and associate professor of art, Sheri Fleck Rieth.

Craven’s expressive linework and deep shadows depict a child’s cracked teeth, protruding ribs, emaciated arms, and what could be a belly bloated by starvation or a pregnant girl unable to feed herself or her fetus. An empty fishing pole in the child’s left hand and the work’s title make the figure a powerful poster child. Instead of raping the world for quick profit, Craven suggests that we leave enough natural resources intact to allow humanity to farm, fish, and fend for itself.

Through August 9th at On the Street

This has been a long, rich day, but we’re not done yet. We stop by the P&H Café for one last cup of coffee.

On the wall behind the bandstand, also known as P&H Artspace, is Gadsby Creson’s installation, “The Price Is Even More Right,” one of the smallest, most original shows in town.

Each of Creson’s mixed-media paperworks is mounted on two 4-by-4-inch squares of foam core. Some of the works are glued to the foam core like tiny abstract paintings. In others, the foam-core squares serve as backdrop and stage for minuscule paper sculptures.

Two of Creson’s most dramatic pieces suggest a line of narrative. In the first, a Matisse-like dancer moves with frenzied grace above a dark-red sea. In the second, another ebony figure folds her body onto the floor like a dancer taking her final bow.

Creson’s dancers are a good way to end our day. I’m headed home to begin writing this column. But stay as long as you like. The P&H crowd of music lovers, literati, and art enthusiasts keeps jamming way past midnight.

An opening reception for “The Price Is Even More Right” is Friday, August 8th, from 8 to 10 p.m.

Through September 8th at the P&H Café