Photographer David Horan has traveled around the world and mounted exhibitions of his work in Japan, Czech Republic, Sweden, Germany, Spain, Venezuela, and cities across the U.S. His latest, “Earth: Abstracts from Life,” is now on view at the University of Memphis’ Jones Hall Gallery.

Horan has an eye for the ingenious shapes, the complex textures, and the light that inspire both abstract and landscape painters. In Homage to Rothko II, a golden sunset reflecting off concrete walls and floor transforms a downtown dress shop into a multifaceted abstraction that honors cubism as well as color-field painting. Golden rectangles glow next to blood-red triangles. Edges dissolve, and light floats in light.

Pollock’s all-over paintings, Kline’s bold blacks, de Kooning’s unedited grit, and Robert Motherwell’s Rorschach-like shadows — all can be found in Horan’s close-ups of the crumbling asphalt, tar patches, bird droppings, and house paint spilled on Home Depot’s two-acre parking lot.

In one of Horan’s most evocative images, D.C. Space, early-morning sun reflects off mica in a crumbling sidewalk that’s overlaid with shadows. D.C. Space projects our point-of-view from sunlit sidewalk to what looks like a planet backdropped by a splatter of stars, a meteor in deep space, and a panorama of the cosmos. Beyond metaphor and symbolism, D.C. Space captures a truth as inevitable as death and taxes: In this solar system, it’s all about texture, shadow play, and light.

“Earth: Abstracts from Life” at Jones Hall Gallery through February 15th

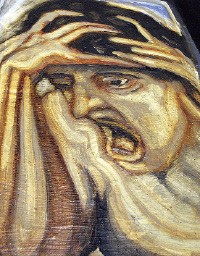

For his current exhibition “In the Quiver of the Kingdom,” Jon Rappleye, an accomplished draftsman and master colorist, fills Clough-Hanson Gallery with mesmerizingly beautiful works of art that look simultaneously Edenic and apocalyptic.

Rappleye’s delicate, detailed line work and nuanced shadows create worlds so fully realized that we see each scale, hair, and feather of the animals. Metal and mica ground into Rappleye’s acrylics become bronze mountains and iridescent blue seas.

The plume of a peacock trails off a gnarled tree in a painting also titled In the Quiver of the Kingdom. The distinctive eyelike pattern of the peacock’s plume hangs down the center of the painting looking incredibly soft and all-seeing.

But all is not well in this Eden. The scenery tells a story of oil spills, toxic dumps, and venomous nectars. A sinewy weave tight enough to serve as barrier against toxins covers the ground and trees. It also chokes off nutrients. Except for mushrooms as eerily iridescent as the visions these fungi sometimes induce, Rappleye’s plants and animals are nearly colorless and look anemic. Some birds lie dead on the ground. Other birds sprout antlers. Some of the birds’ necks become serpents, and the eyes of owls become starbursts of light.

Rappleye is an artist who plunges us into worlds so increasingly compromised that hallucination becomes reality. He immerses us in end times caused not by epic battles between good and evil but by our failure to be good and faithful stewards of the earth. We’re on a fast track to destruction, but we’re not there yet. The final chapter in Rappleye’s visual narrative of impending ecological disaster is not ordained nor etched in stone. It’s still ours to write.

“In the Quiver of the Kingdom” at Clough-Hanson Gallery, on the campus of Rhodes College through February 13th