In contrast to photorealist painters, plein-air painters use no hard edges. Light is constantly in flux, and trees vibrate with wind. “Path into the Wilderness,” John Torina’s exhibition of 14 large, consummately executed oils on canvas at David Lusk Gallery, captures nature’s endless play of color and light with slashes of pure pigment and passages of blazing impasto that punctuate and energize subtle tonalities and monochromatic color fields.

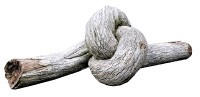

The Eternal Circle by Lisa Jennings

In the spirit of Monet’s studies, Torina follows the light of the Mississippi River Delta from season to season, from dawn to dusk. In Old River Channel, a band of pale peach is bookended by two stands of leafless trees. The channel’s slow-moving water, the silver-blue sky, the skeletal trees, and the pale, nearly translucent sunset capture the look and feel of a crystalline, cold winter day. In Scarlet Summer and Sunset Over the Delta, Torina captures the fiery temperatures, humidity, and haze of summers. Deep reds (cadmiums, crimsons, and siennas) fill the sky, tint the vapors above the river, and reflect off large swaths of the wet Delta lowlands.

At David Lusk Gallery through February 24th

George Shaw’s Study for Poet’s Day

For 26 days during the summer of 2006, Lisa Jennings hiked the west coast of Ireland near Galway. And she painted — producing a body of work that constitutes “Threshold,” the exhibition at L Ross Gallery.

In her previous shows, ghostly figures, black ravens, and white doves were often superimposed on ethereal dreamscapes. Painting the Irish landscape on site has taken Jennings to a whole new level of art-making. Her mixed-media paintings are rich with the colors and textures of Ireland: the deep-purple heather, the red jasmine, and the infinite greens of the rolling hills. They are rich with ancient iconography as well, recording sites of ritual, stargazing, and burial, where prehistoric peoples erected large stone megaliths and circles of standing stones.

Jennings’ new work is also filled with personal symbolism. In Crossing the Unknown Sea, one of the standing stones morphs into the silhouette of a woman standing in a shallow sea, her feet planted on the ocean floor, her head turned to the right and gazing out to sea. Next to the figure is a curragh, an open boat covered with hide, which transported the ancients and their megaliths between coastal islands. This curragh, whose golden oars nearly touch the luminous figure, stands ready to carry a visionary artist deeper into the Irish landscape, deeper into the mind-set of millennia of humans burying their dead, studying the movement of the stars, attempting to understand the universe.

At L Ross Gallery through February 24th

Since childhood, George Shaw has sketched and painted his birthplace, Coventry, England, and is internationally noted for his meticulously rendered paintings. For his exhibition “A Day for a Small Poet,” however, Shaw quickly executed 19 enamel paintings on small pieces of cardboard, which are tacked to the walls of Clough-Hanson Gallery at Rhodes College. This format is poignantly apropos for a body of work in which the remains of an ancient forest and 15th-century graveyards stand alongside strip-mall shops, prefabricated housing, and abandoned garages.

In one of the untitled works, a huge tree trunk, decayed on the forest floor for centuries, is surrounded by litter from a nearby housing complex. Study for Lychgate depicts eroding medieval gravestones and the gate where the dead were laid beneath shrouds (only the well-to-do could afford coffins) until the priest performed last rites. The exhibition’s most provocative work, Study for Poet’s Day, is a weathered, blood-spattered garage in Tile Hill, the public housing complex in Coventry that has gained the reputation of being one of the roughest places in the U.K.

“A Day for a Small Poet” is a fitting title for a show in which a respected painter returns to sketching and to his roots. This body of work pays homage not to the rich or famous but to small poets — like the talented youngster who lived with his working-class parents in Tile Hill housing and honed his artistic skills sketching the buildings and trees of Coventry.

At Clough-Hanson Gallery, Rhodes College, through February 21st