On any given day, dozens of Memphis musicians are crisscrossing the country, bringing the diverse sounds of our city to audiences large and small. It’s a fun life, but things don’t always go as planned. It’s a tradition for musicians to swap stories of disaster, humiliation, and stiffed payments. Here are some prime cuts from Memphis musicians who were willing to go on the record about their worst gig experiences.

Dead Soldiers

Krista Wroten Combest — Dead Soldiers

We were on our way from Asbury Park to Brooklyn, and then to Staten Island. The guy at the toll booth told us the wheel on our trailer was smoking. This wasn’t surprising to us, because on our last tour, the wheel had fallen off as we were attempting to leave Sister Bay, Wisconsin.

That’s why we weren’t surprised when it happened again in New York. We pulled over and called a bunch of auto places, but no one was open, so we decided to take it easy and just get to the show. We limped into New York and somehow made it through the Staten Island tunnel, which is more than a little terrifying when you’re hauling a broken trailer behind a conversion van.

We finally made it to the venue and had a great time and got to party with a bunch of our Memphis transplant friends. Loading out after the show, Clay [Qualls] accidentally broke the key off in the lock on our trailer. It ended up being easier to just tear the trailer door off rather than deal with the locks and load all our stuff into the U-Haul we rented for the rest of the tour. All the while we were being harassed by a junkie who looked like an extra from The Nightmare Before Christmas. We had to make the tough choice to abandon our trailer there in the Big Apple. Another victim of the road. R.I.P. trailer, I hope you’ve finally found peace in some scenic New York junkyard — or as a Brooklyn hipster’s apartment.

Joey Killingsworth — Joecephus and the George Jonestown Massacre

I got so many bad stories…

We drive to the middle of Georgia to play a car show. And to get there, you had to get walkie-talkied in. One car at a time on this little gravel road in the middle of nowhere. Once you got down to it, there was a field with all of these cars and stage in front of a dirt track. We start talking to people, and these rednecks are scary even for white folks. Dave said, “You took me to a Klan rally where they don’t bother to wear hoods.” These motherfuckers were crazy. These guys were showing us their gun wounds, their knife wounds. I was like, this is a little too much for us.

There was a guy in a blue gorilla suit playing upright bass, doing ‘White Wedding”, and some ‘80s songs. He was cool. But then we got on stage, and the wind started blowing towards the stage. Whenever the cars would drive behind us, the dirt would blow up on us. It was covering my pedals, my guitar, everything.

As soon as we got done, we were like, we gotta get paid and get the hell outta here. But they were like, hang on, we have an emergency. Somebody broke their foot. We’re waiting on a helicopter. We were like, why don’t you just get the ambulance? No, he was some drunk redneck on a quad runner, and his foot actually broke off, like, it came off. So they had to airlift him out. And that was Dave Wade’s first show with us. He said, ‘That was the day I said, ‘I’m never going to do this again.’ That was six years ago.

My personal worst was the Hogrock festival in Illinois. It’s in the middle of a field that they used to use for the Gathering of the Juggalos. There are three big stages. You gotta follow trails in the middle of nowhere to get to them.

At first it was awesome, but it turned out that was the night the cicadas came out. Like, they were literally emerging from the ground. We were in an open area in the middle of the woods. Me and Brian [Costner] were not wearing shirts, and Daryl [Stephens] from Another Society was playing drums. The cicadas were swarming all over us. They stayed on us the whole time. They were swinging on the bill of my cap, hanging off of my guitar. It was like somebody throwing softballs at you. I would kick a bunch of ’em out of the way to get to a pedal. Daryl said he was just playing and cringing, watching these cicadas climb on our backs. We did an hour and a half set. It was like that the whole time.

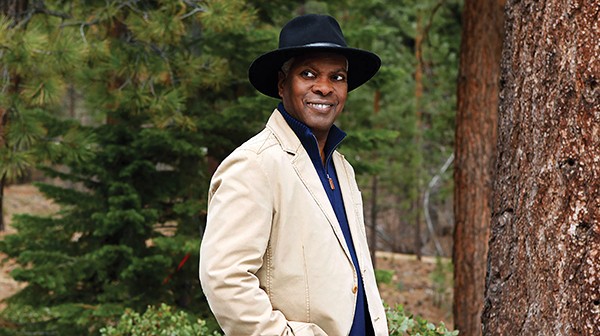

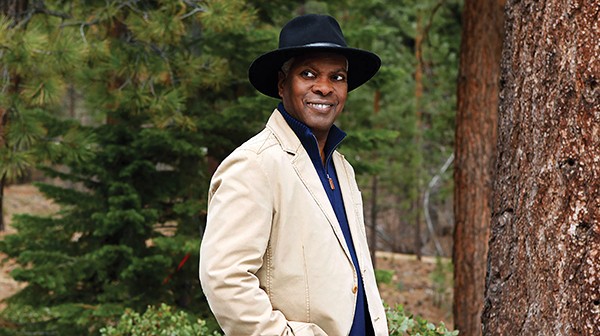

Marco Pavé

Marco Pavé

I was 15 years old and auditioning for a talent show in the Frayser High Gymnasium. I had downloaded the beats from a site called Soundclick, and at the beginning of the beat, there was an audio tag that said I didn’t purchase the beat. I downloaded it from the internet so I could perform! I was 15 years old! I didn’t know!

So I came, I had my songs ready, I performed them, I rocked the songs. Then the guy was like, “Yeah, man, you had the tag on your beat. That means you’re not serious. We would have picked you if you had used a professional beat or a beat that you owned.” Basically, they took my $50 submission fee as a 15-year-old and told me to go home.

Booker T. Jones

Booker T. Jones

I drove from Memphis to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, not long after we had recorded “Green Onions.” I think they told the people that I needed an organ, so they went to the church and got a pipe organ. They didn’t tell them it needed to be a Hammond B3 Organ. It was a simulated pipe organ with stops — a spinet. It was like a church organ — the notes didn’t make a sound right away. It wouldn’t work. I ended up trying to play “Green Onions” on a pipe organ in this club in Baton Rouge. That’s got to be the weirdest sound I’ve ever heard.

Richard Dumas

Richard Dumas

Lorette Velvette

Lorette Velvette — Tav Falco’s Panther Burns

It was 1986. We’d been up in NYC. “The Starvation Tour.” Bob [Fordyce] would just write “FOOOOOD” in his sketch book. So we were crowded in the car, and we had no money. George [Reinecke] was sent into a country store somewhere along the way, and he bought white bread and some head cheese nobody else would touch. So all I was eating was white bread.

We went down to the Metroplex in Atlanta. We started our show, and I was on stage playing tambourine. During “Tina the Go Go Queen,” two policemen came up and told me to come off stage. And I said, “No! Wait till the end of the song!”

Then I went off stage into this other room with them. The Panther Burns kept playing. And so the policeman wrote me up and said, “I’m giving you this ticket for playing tambourine without a permit.”

I was so mad I snatched the ticket from his hand, but he didn’t let go. He held onto the ticket. I just turned away from him, just looking at the heavens, going, “God, this is bullshit!” Then he grabbed me from behind in a big bear hug and ran me out the door, several yards, onto the sidewalk.

By then, the Panther Burns had gotten out there. Tav was begging him to not arrest me, but they said I had “resisted arrest.” This was the police officer who had bear-hugged me and his senior sergeant. The two of them conferred: “Well, should I take her in?” And the sergeant said, “Well, you’ve already laid your hands on her.”

Immediately, the paddy wagon was there. Back doors open, I get shoved in. And Tav was begging him, he was like, “Please, please, don’t arrest her!” And before the doors shut he said, “She’s been eating white bread for a week!”

They took me to the downtown jail, and I had to stand in line. I was dressed in my pink vinyl miniskirt, with a black half top and go-go boots. They all thought I was a prostitute, so they put me in the cell with a bunch of other ladies. When I walked in, they all wanted my cigarettes, so I gave out my cigarettes to make friends. There was a telephone in the room, and they’d get on the telephone and call their husbands and tell them not to press charges. Like, these women had beaten up their husbands. Several of them.

My bail was $1,500. Around daybreak, the Panther Burns came and I was like, “How did you make bail?” It turned out, the people in the club had chipped in, the club had chipped in, and the pizza place at Little Five Points had chipped in a bunch, and they got the money together and got me out. I had to go to court literally the next day. A lot of people came from the club, saying, “They’ve been trying to shut us down for a long time.”

There was a lawyer assigned to me who said, “Let’s try to settle this out of court.” He made a deal, that they would drop the charge of resisting arrest — and I probably weighed 105 pounds — if I agreed not to sue them. Of course, I couldn’t, because we didn’t have any money. And I didn’t want to ever go back to Atlanta again.

Marcia Clifton — The Klitz

The worst one, probably, was the one that should have been the best, when we went to New York to open for the Mondo Video film. Remember Mr. Bill? And Michael O’Donoghue. He was a writer for Saturday Night Live. We opened for his movie, Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video. Sept. 23, 1979 at the Times Square Tango Palace. Elizabeth Johnson was a girl from Memphis who went to Harvard, and she got in, like, a cool crowd and suggested us to play for this. And of course they heard the name and they were like, “Oh yeah, the Klitz!” It was perfect.

And so we were just kinda like…we weren’t really tight, because we were nervous, and I think we had had too much to drink. Rolling Stone was there, and we got a review in Rolling Stone and it said, “The only thing worse than the Mondo Punch was the entertainment.” That was a quote from the actress Sylvia Miles, who appeared in Andy Warhol’s Heat. They flew us up there, put us in a hotel, we went to all the parties, and then, when it was time for the gig, we just kinda fell apart. It was kinda sad.

Stephen Sweet

Stephen Sweet

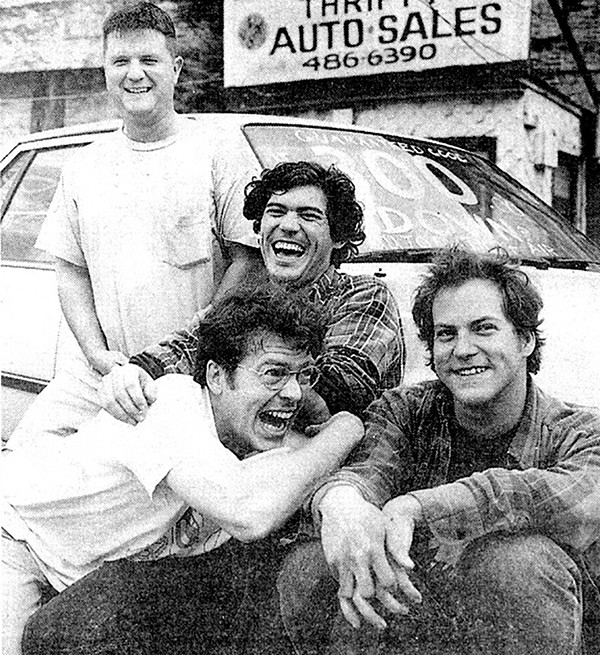

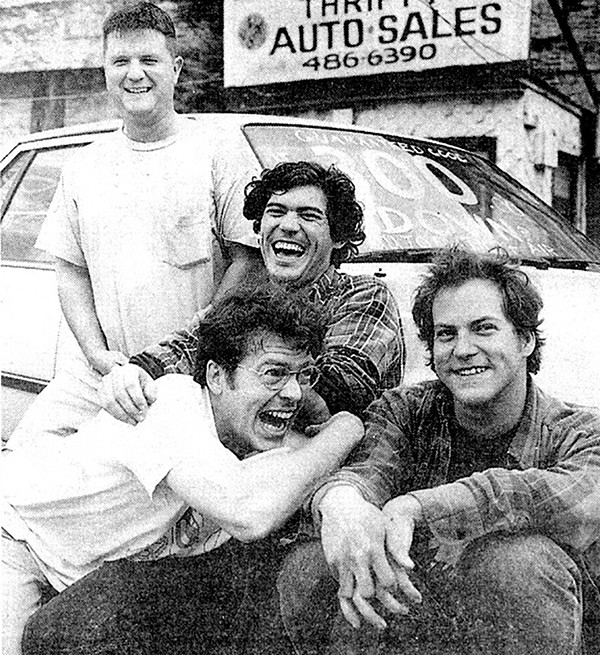

The Grifters

Tripp Lamkins — The Grifters

I think it was 1992. We were on a month-long tour with Flaming Lips and Codeine. We were in Atlanta at a club called The Masquerade, which was split into three levels. You entered mid-level into Purgatory. The bands played upstairs in Heaven. The sub-level was a red-lit, S&M-themed bar called Hell. Of course, we went down to Hell.

The bar was just opening, and the only other person in there besides the bartender is a guy playing pinball. Shirtless, muscular, black leather pants, black boots, black policeman’s hat, handcuffs. We ask if he’s a regular. Bartender says, “No, that’s Frank, the bouncer.”

Later, we play our set. Good show — hard not to have a good show on that tour. It was the biggest crowds we’d played to up till then. We’re sitting backstage having after-show beers. There’s a knock on the door.

This guy peeks his head in and asks, “Grifters?” We’re like, “Yeah.”

He creeps in with two friends in tow. He tells us how glad they are we came back to Atlanta and that we killed it out there. Of course, we’re grateful and invite them to hang.

They sit down, and dude continues to blow smoke up our asses. “You guys are blowing up! Every song was killer! I bet you’re blowing Flaming Lips off the stage every night! Mind if we grab a beer?”

Dude grabs three beers, hands two off to his friends, and continues to ramble. “This new record man. It’s friggin killer!” Kills his beer. Grabs another one. “Man, you guys are gonna be fighting off the majors!” Kills that beer, grabs another.

Then I see him give a sideways glance to his friends and he asks, “Man, what’s the third song off of side two on the new record?” I say, “Encrusted?” He says “YEAH MAN! ‘ENCRUSTED’! The guitar solo on that song is friggin’ DOPE!”

I say, “Okay, this has been fun. Time for you guys to go,” and they leave. I turn around and Scott and Stan are like, “What’d you do that for?” and I’m like “There isn’t a guitar solo on ‘Encrusted’! We don’t have guitar solos on any of our songs!” And it sinks in. We’d been grifted for backstage beer.

Stan says, “We’re not gonna let him get away with this are we?” I say, “Hell no!”

The club was packed, and the Lips were raging loud. We didn’t know what we would do. After casing the place, we decided to wait by the men’s room. It worked. Almost immediately, dude walked right by us, swigging beer and laughing and — I’m not kidding — he actually says, “I stole this beer from the Grifters! Haw Haw Haw!”

So we’re thinking, “This guy’s going down!” But we only have moments to formulate a plan. We decide we would appear to be fighting each other when dude comes out of the bathroom, and then Stan would hurl me at him and I would either knock him down or knock the beer out of his hand.

Stan and I start shoving each other around and cussing at each other for what seemed like five minutes when finally the guy comes out of the men’s room. Stan grabs me by the lapels and throws me at the guy—who casually sidesteps me! As I’m falling backwards, I reach out and just knock his beer to the ground. It shatters on the floor, and he flies into a rage.

He screams, “That was MY beer!” Stan jumps to my side and points in his face and says, “A beer you STOLE from the Grifters!” He looks all kinds of confused and then goes into a Three Stooges, Curly kind of wind-up. Stan and I plant ourselves, then suddenly Frank the S&M bouncer comes from behind us and hurls the guy into the wall and says, “GOD-DAMN-IT, BILLY! HOW MANY TIMES WE GOTTA DO THIS?”

Frank shoves the guy’s arm into his back and gets him in a headlock and then drags him backwards down the stairs literally kicking and screaming. We looked down over the banister and Stan yells, “This is what happens when you fuck with the Grifters!”

Herman Green — B.B. King

I played with B.B. King a couple years. He saved my life, man, ’cause he didn’t have a car, and I had a car. And so we’re coming back from Blytheville. They had those narrow bridges in Arkansas, and we was following this truck with a trailer. And he signaled, another one coming toward us, some kinda way they had a signal, and told them to come on, don’t stop. And it had been raining. I wasn’t driving, the piano player was. And he hit the brakes … no brakes. We hit that bridge and knocked up three concrete posts, and as fast as we were going, we couldn’t stop.

I felt something go across my chest, like someone was fighting me. It was B.B. and the way he did it, he took his left arm and went that way, and he balanced himself on the bench. So he wasn’t going no where. ‘Cause they didn’t have seat belts back then. That was back in the late ’40s, early ’50s. And he saved my life, because I’d a went through the windshield.

And then, you’ve heard of Ford Nelson at WDIA, haven’t you? He’s a disc jockey. He was with us. He weighed about 240 pounds, and after we hit those concrete posts, the car was laying right on the edge of the bank, teetering. Ford got out one way and the car went the other way. And we slid down and the hood got right in the mud down there. And I told Ford, I said, “Man, don’t you ever move! I don’t care where we at, just sit still!”

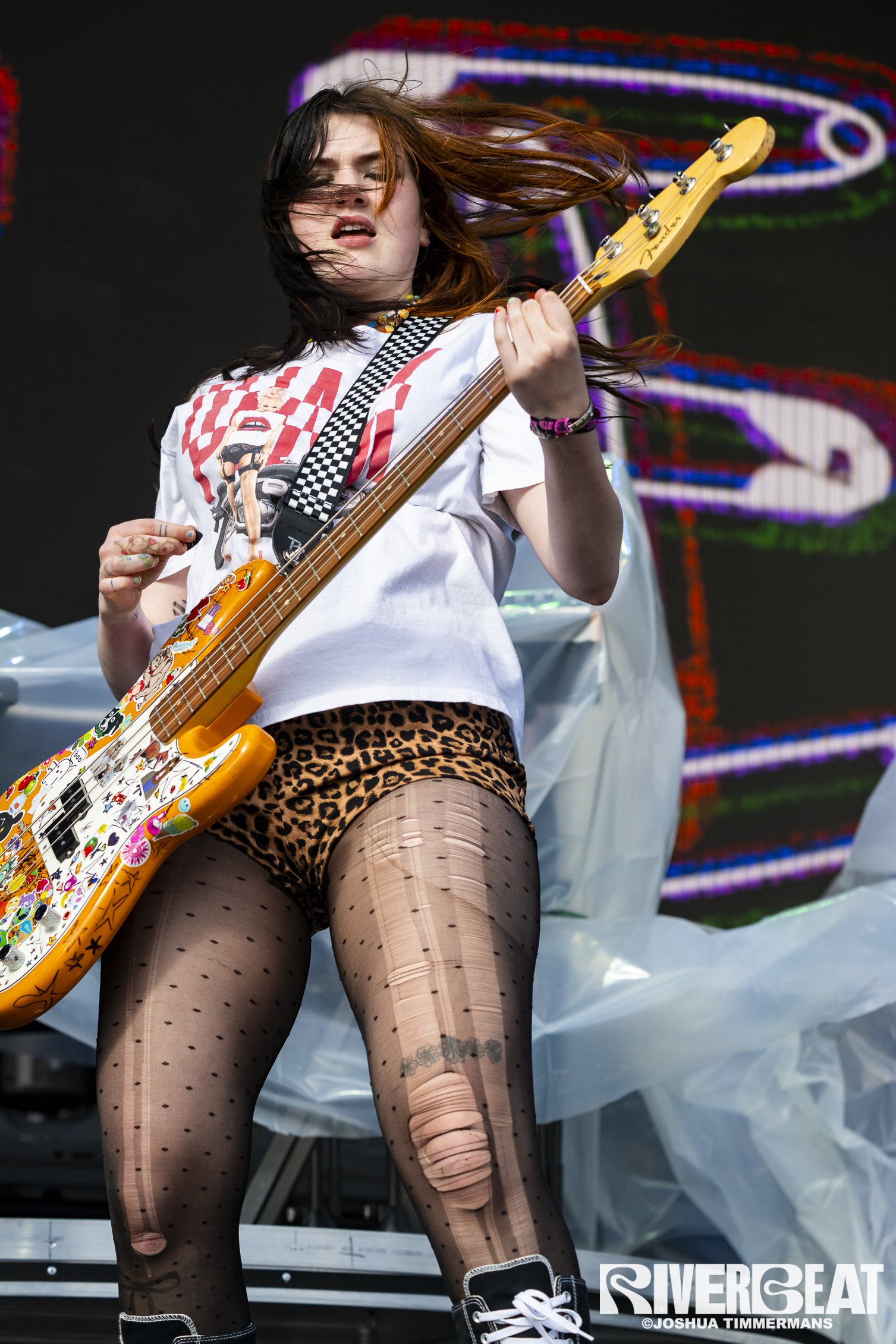

Kelley Anderson — Those Darlins

Those Darlins played the 2009 Americana Music Festival in Nashville and were scheduled to play before John Fogerty. Creedence Clearwater Revival was one of Jessi [Zazu]’s favorite bands, and she was excited to get to see him.

At the last minute, Fogerty decided he wanted to play earlier. The festival organizers accommodated his request (because he’s John freakin’ Fogerty) and shifted our scheduled time to be after his. All performers were supposed to play around 45 minutes, and he rocked for almost two hours. At one point, there were three guitars on stage — there were so many guitars.

After he completely rocked everyone’s faces off, we set up our ragtag equipment in front of theirs on the stage they just destroyed and basically played outro music for the waves of people filing out of the Mercy Lounge.

Their drums were still set up on a giant riser, so Linwood [Regensburg] set up his kit in front of theirs, and the rest of us kind of filled out to the side, with me playing behind a large column. With no soundcheck and a “Here goes nothing!” sigh, we took it in stride and played a good show for the 20 or 30 diehard Darlins fans who remained up front. So maybe it wasn’t the worst gig ever, but it was a little embarrassing to be playing to such a large room of people leaving. But hey, not everyone can say that John Fogerty opened up for their band!

The Reigning Sound

Jeremy Scott — Reigning Sound

The day after opening for the White Stripes at the White Blood Cells album release in Detroit, the Reigning Sound rolled into Columbus, Ohio, for a gig that night. It was at Bernie’s Distillery, a long-running local institution. We were under the impression, probably from the guy who booked the tour, that Bernie’s had a kitchen. The key word here is “had.” In fact, the whole place looked like it had been closed for at least three years. (Bernie’s soldiered on until the end of 2015, incredibly.) When we asked to see a menu, the dude behind the bar said, “Um, our kitchen closed a few weeks ago, but hang on a sec,” and headed where we couldn’t see him. When he returned, he informed us, “Well, there’s a whole ham back there. The top part is green, but I could shave off the bottom for you and make sandwiches.” We all looked at each other and said “Nah, we’re good.” Add in the thoroughly disgusting bathroom which gave ’70s-era CBGB a run for its money, and a bunch of out-of-place Ohio State grads, and you have a fairly disorienting experience. That’s life, though. One day you’re playing with the White Stripes, the next day a random bartender is trying to kill you.

The Masqueraders

Harold Thomas — The Masqueraders

[In 1968, the Masqueraders hit the road to support their hit “I Ain’t Gotta Love Nobody Else.”]

Our first engagement on that tour was at the Apollo Theater. This was the craziest experience we ever had in our life. We got up there, we were just ol’ country boys. We didn’t know. We really came from a capella, to the studio, and now we gotta have music. We didn’t know we needed charts!

We get to the Apollo Theater, and the bandleader goes, “All right, Masqueraders, let me have your charts.”

We go, “Charts? You know, we always just go, ‘Well, the music goes like this, dowmp dowmp dowmp!'”

They go, “Oh no, man … we need some charts.” Okay.

So one of those guys says, “Hey, I tell you what, I know the song. You all give me $50, and I’ll write the charts for ya. Tonight, when y’all come back, I’ll have ’em ready.”

That night, they call us, “Masqueraders, Masqueraders, you’re up next!”

We run out on the stage, waiting for them to play our song. They didn’t play nothing like it. It wasn’t nothing like it! We was looking at each other going, “What the … hell?”

And the people in the audience, they were starting to mumble, getting ready to throw tomatoes and eggs. You know how they did back in the day.

So one of our guys said, “Hold it, hold it, man, we don’t need no music! We don’t need no MUSIC. Stop right now!”

And then he headed out on that melody [a capella], “Up in the morning …” and we were like “Wooo-ooh.” “Out on the job … ”

When we got through singing that song, they were standing up, you hear me?

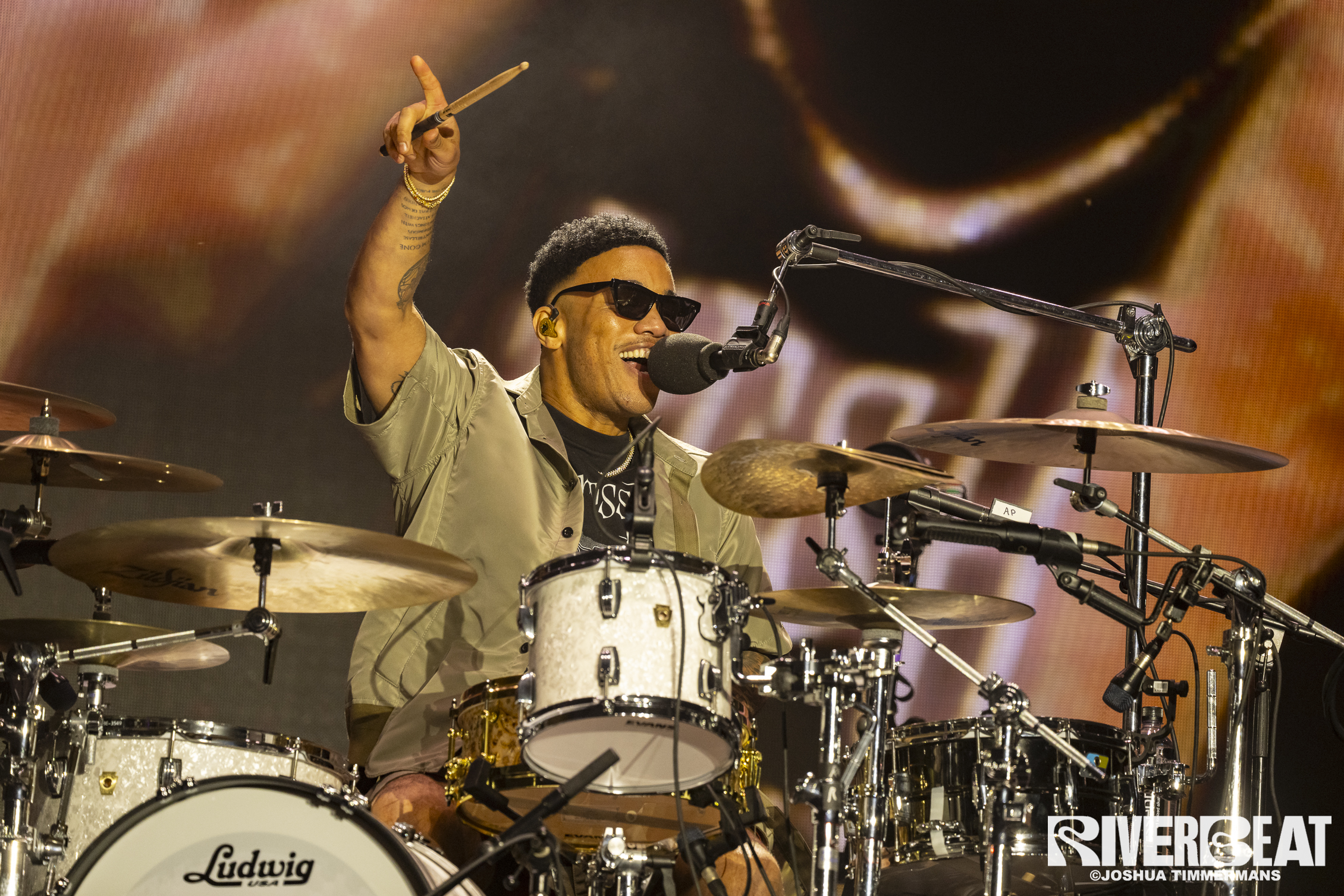

Richard Dumas

Richard Dumas  Stephen Sweet

Stephen Sweet