Tommy Lee Jones’ feature directorial debut, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada is about what happens between two groups of people that are in the process of merging. Individuals thrown together by accidents of geography and economics can unite despite classism, racism, or tribalism, because friendship is stronger than those -isms.

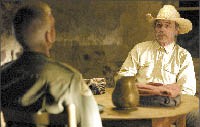

Jones plays Pete Perkins, a ranch hand who befriends Melquiades Estrada (Julio Cedillo), an illegal immigrant cowboy who is somewhat naive but unfailingly kind and fair in the way that Americans like to believe cowboys are. When Estrada turns up in a shallow grave in the desert, it is a foregone conclusion among the small-town Texans that no one will ever find out who fired the shot that killed him. Their attitude toward the illegals is summed up when Perkins asks Sheriff Belmont (Dwight Yoakam) to be notified when his friend is buried.

“I don’t have to notify you of a goddamn thing,” Belmont says. “He’s a wetback.”

When Perkins stumbles across the truth — that his friend was accidentally shot by a border-patrol agent named Mike Norton (Barry Pepper) — his demands for justice are ignored, so in true Western fashion, he takes matters into his own hands, kidnapping Norton and setting off to give Melquiades a proper burial in Mexico, “away from all these billboards.”

The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada is firmly grounded in the morality-play tradition of the Western, but writer Guillermo Arriaga, who penned Amores Perros and 21 Grams, takes pains to leave his mark on the story, and both the film’s strengths and weaknesses are similar to the writer’s earlier works. Arriaga breaks up the story’s beginnings into a nonlinear structure before settling into a more conventional second half once the dramatic situation of the two men traveling through the hostile desert has been set in motion. But Arriaga and Jones recognize that the situation is as much Weekend at Bernie’s as it is Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and throw in an occasional wink. Arriaga is interested in the way communities of people are connected, sometimes to the point of forcing connections between characters that are unlikely and distractingly unnecessary to the story.

But Arriaga’s wry fatalism is strangely satisfying, and his screenplay provides the backbone for great performances by the principal cast. Jones channels Unforgiven-era Clint Eastwood, never quite rising to the tortured heights of John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards from The Searchers, but making Perkins’ at times irrational choices seem understandable. Pepper’s TV-and-porn-numbed border-patrol agent epitomizes the banality of evil.

After Men in Black II and Man of the House, it seemed like Tommy Lee Jones was going to be content to coast to payday after payday until the calls from his agent stopped coming, but The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada suggests a more Eastwood-like trajectory, where a tough guy matures into a tough-minded artist. With his first feature, Jones has set the bar pretty high. Here’s hoping he can keep it up.