We are all familiar with Lifetime movies of the week that are based on a true story. In reality, this is almost never the case, as the story is edited, facts are omitted, and certain aspects are fetishized in order to make the story more interesting for the viewer. Is it not in our nature to embellish such stories — either for comedic effect, TV ratings, oratorical flourish, or simply to make the “true” story better? Intentionally or not, we all take liberties with our tales and desire such embellishments in the stories that are told to us.

Joel Carreiro, professor and director of the graduate programs at Hunter College, is interested in the many different forms of such storytelling. Carreiro is the curator of the current exhibition at Marshall Arts, “Based on a True Story,” which runs through February 23rd.

“[My] initial interest was how many artists are tackling the issue of narrative in their work in interesting and exploratory ways,” he says. “Storytelling is the primary way people respond to life and try to understand it as life flows by.” He suggests that perhaps there is only fiction, that “any story has been shaped and structured in order to be a story at all.”

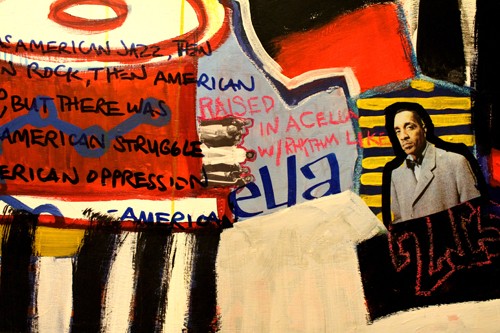

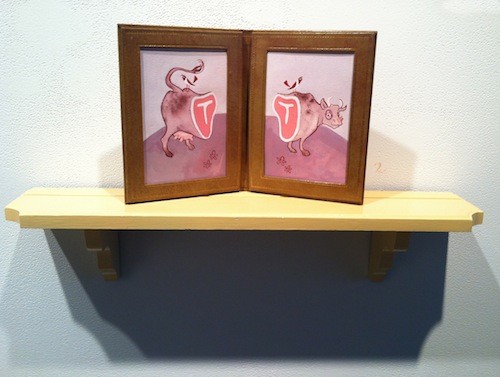

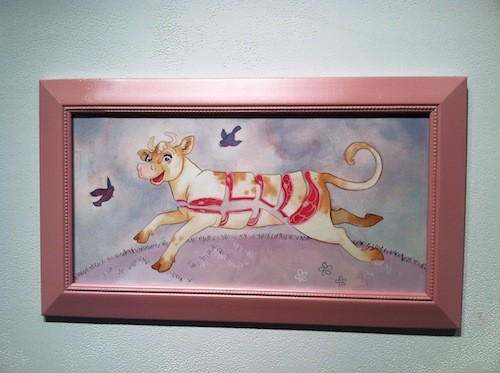

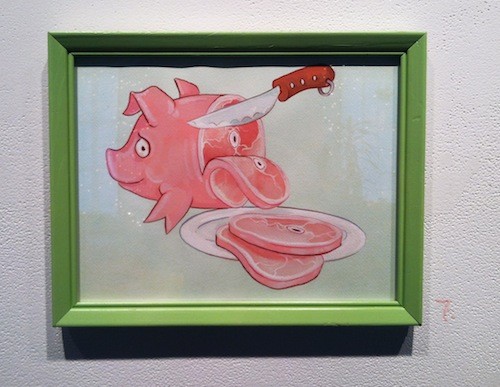

The three artists in this exhibition — Yeon Jin Kim, Christopher Miner, and Matthew Garrison — take various approaches in constructing their narratives. “True Story” is a multimedia exhibit with many parts — video, drawing, photographs, performance, and sculpture.

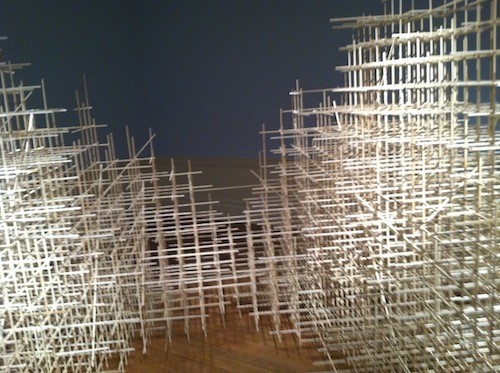

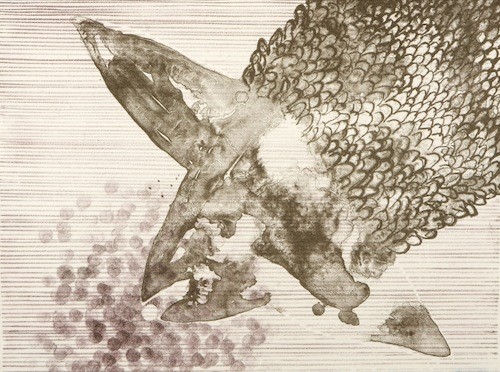

The images and situations in Kim’s work, Carreiro notes, “encourage us as viewers to fill in a story that might account for what we see.” In Spaceship Grocery Store, Kim gives us a robot character that looks like WALL-E or Johnny 5 from the film Short Circuit as it meanders through the aisles of a flying-spaceship grocery store. Her intentionally rudimentary animations are created from scroll drawings that are hundreds of feet long and objects that are made from everyday household items. The audio component, which is best described as the sound of a rewinding cassette tape, can be heard throughout the gallery. It is nerve-racking but works with the makeshift-looking animation.

Miner has a video projecting in the small back room of the gallery and several videos rotating on a flat-screen TV in the main gallery. From rethinking his marriage while on his honeymoon in Acapulco, to being overprotective of his infant son, to agonizing over uncooperative nose hair, Miner’s work is a running autobiography. In the video Right Now Is the Place To Be, Miner, while bouncing his infant on his knee, is singing a lullaby. It is an endearing moment, until you hear that the song he is singing is Mystical’s “Shake Ya Ass.” The piece then becomes a spectacle, embracing the notion that it is not what you say but how you say it that counts.

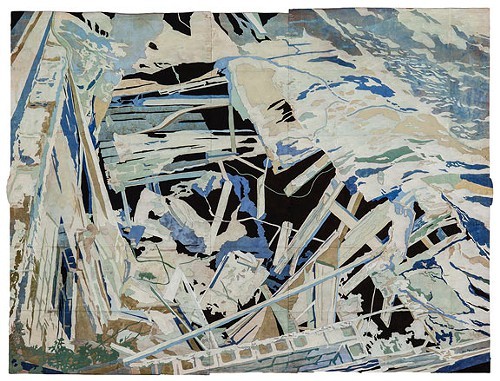

Garrison’s Be Right Back, the largest piece in the exhibit, consists of 3,078 4″ x 6″ photographs of empty rooms. Garrison spends hours in online video chat rooms. He does not interact with any of the people; he is waiting for them to leave their rooms so he can take the necessary screenshot of the space.

Garrison hopes that “questions as to who these occupants are and where they’re from spark the imagination, while the accumulation of so many intimate spaces becomes unsettling.” It is unsettling. Unsettling, at least for me, because of the acknowledgment that I am indeed a voyeur, and I find it interesting that these people, under the assumption of online anonymity, open up their lives and private spaces for the world to see.

“Based on a True Story” succeeds in demonstrating how narratives are constructed and the liberties we take as artists to tell these stories. It also leaves the question “what is true?” unanswered.