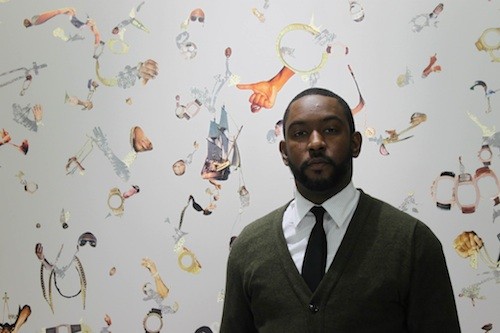

Lester Merriweather has been doing a lot with Memphis art for the past decade, but 2013 may have been his most remarkable year to date. In addition to curating the University of Memphis’s new Fogelman Gallery, he was featured in group shows at The Cotton Museum and Material and held two excellent solo exhibitions, “BLACK HOUSE” and “WHITE MARKET”, at South Main’s TOPS space. He produced an entirely new body of collage pieces, worked with ArtsMemphis and the UrbanArts Commission, and was a constant presence at openings and events throughout town.

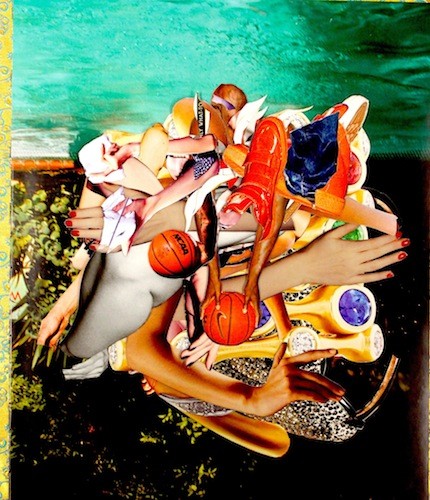

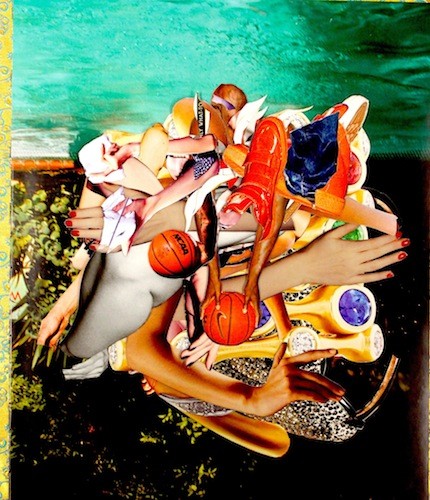

The first time I visited Lester’s studio, I found him standing several rungs up on a ladder, affixing a picture of a bejewled female wrist to the top of a 12 foot canvas. He was putting the finishing touches on the body of collage work that would form the first half of his solo exhibition at TOPS. Around us, glossy magazines were stacked floor-to-ceiling, along with Tupperwear containers full of carefully extracted clippings.

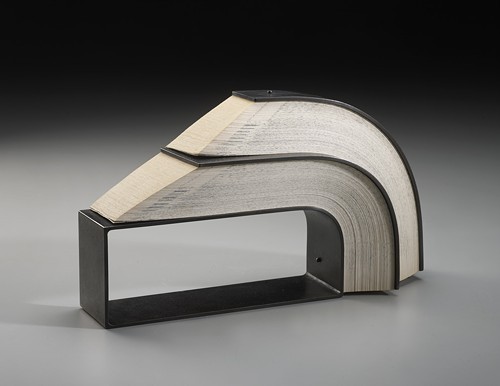

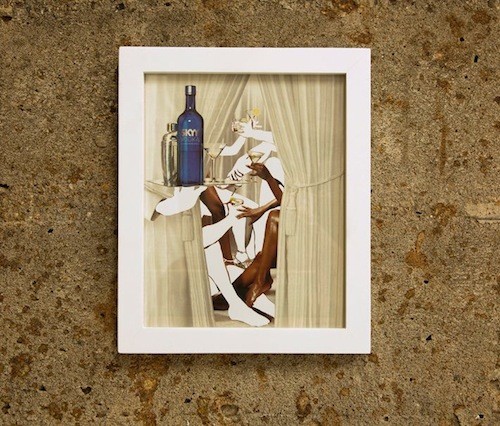

The collages, many imposingly large yet sparse, feature delicate wreaths of jewels, sunglasses, watches, lipstick, and other luxury ephemera. These images are interspersed with deconstructed pictures of celebrities, or parts of celebrities. The works are about wealth and race and pop culture, and about how human bodies are co-opted by the brutality of capitalism. In following weeks, hanging in the grimy TOPS basement, they looked both bleak and luxe.

I recently visited Merriweather in his studio for a second time, to talk about 2013 in Memphis art and in his work.

Flyer: You devoted this year to making work and showing work in Memphis. As an artist who has shown internationally, but who has spent his career here, what was that like?

LM: It’s a mixed bag. You always have positives and negatives from situations in which you are exhibititing work. There were high moments, like being able to do the 100th show at Material. I think everything came from just wanting to focus on changing things in my studio, and developing different bodies of work that I had started on, and just wanting to get actual ideas materialized.

There is a long way to go for Memphis’s communities, in terms of how they receive, understand, and support art. But a lot of my work, this year, was to achieve that specific goal [of making and showing work in Memphis]. TOPS was a highlight, because I felt like I got a chance to do several different types of work, and make them all work within the space. There are two other Memphis shows coming up on my radar. But I want to use this next year to travel [my work] to other museums and other spaces, and other places….The thing about Memphis is— you could say sometimes— the audience is relatively particular… it is not like you will be blackballed from the art world if you make a misstep here in Memphis. I had the freedom to do whatever I wanted to do.

[jump]

How are things in Memphis for artists now and where do you see things going?

There have been setbacks, like what happened with the Powerhouse [closing]. There have been major positives for what could happen, like for instance, the crowd that was at the Theaster Gates talk, or the Eggleston Museum that is coming in the future. There is always a fluid motion for what the audience could be. I think once there is an actually financially supportive audience, then we will be able to talk about what Memphis really could be.

What do you think we need? Could you elaborate on that? Buyers or institutional support?

We need both. Artists need to have more opportunities. I just sat in on an ArtsMemphis [ArtsAccelerator grant] meeting, and it was its own process, but there was a strange feeling, when it was over, that there were so many artists who needed to be supported. There were so many artists who deserved to be supported. It was, what’s the phrase? —a double-edged sword. I saw that whole process from beginning to end. A lot of people deserved to be fought for more, vouched for more. Not that the people who won didn’t deserve it. There were just a lot of people who deserved it.

Moving focus, there is an overt discussion in your most recent work about racial history. But, maybe as a corollary, I also noticed that many of the scenes have a mythic quality… multi-armed women, or shining blue seas. It is almost Odyssean. It feels like a deconstructed hero-myth. Am I right about that?

I don’t know that I would call it a myth. It is more that these [historical] things have not had a chance to be realized, or that the ideas have not come through. And it kind of becomes obvious in the way that we still look at these magazines, and we still see all of these specific ads, and we don’t neccessarily connect the history between why these ads exist now. We don’t connect them back to the original conquests and voyages.

You know, all of those things also tie into how society is right now, about how hierarchies exist, but no one talks about it. It’s talked about in terms of, “Oh, this is everyday society and this is how things are”, but there are these connections that really ought to be made. Some of those pieces had a “mythical quality”, but I think it is only because no one wants to talk about the multi-headed monster of consumer nature, or capitalism. No one wants to talk about those things in terms of what they really are, from a historical standpoint. While they have a mythic individual nature, when you look at them together, the reality sets in about why we are where we are today.

It it interesting that you can make something that is explanatory of violence, but have it be beautiful. Particularly in light of a discussion of capitalism, that these pieces can be works of art, but also beautiful objects.

You have the idea that things are attractive as pieces of art, as quote-unquote luxury goods. But at the same time, I guess that is where the politics come in. You communicate bigger picture issues with that beauty, but you don’t neccessarily have to beat anyone over the head to come up with a way of communicating.

Can you tell me about your work as a curator, versus your work as an artist? Does being a curator change the way you think about making work?

I wouldn’t say that [working as a curator] changes my own specific work, because I approach Fogelman’s gallery as an artist. There is this list of really specific things that any artist wants. They want to be able to come into the space, envision their work, see it shown the way they want to see it. They want to not have to worry about where they are going to stay or what they are going to eat, the flight, the per diem, all of those basic things that any artist really cares about. At the end of the day they want to see their work shown the way they want it, and they would like for it to be reviewed…favorably, they hope. [laughs]

As an artist, I come into the Fogelman situation understading what artists want. So that is what affects the majority of what I try to do with the gallery. I try to find the best possible artists for that space, for that situation, the best possible installation artists — people who are making cutting edge work, who give prime examples for the students to be inspired by.