Memphis-born and Memphis College of Art-trained, artist Tommy Kha is fresh out of Yale with an MFA in photography and is making waves in the New York art world.

The past months for Kha have included group shows at Chelsea’s Aperture Gallery (“Shannon”) and Brooklyn’s Signal Gallery (“Blog, Re-Blog”). He is slated to be in the upcoming exhibition “Ego,” at Chicago’s Zhou B Art Center, as well as Miranda July’s project “We Think Alone.”

For “Blog, Re-Blog,” 100 photographers selected the work of another 100 photographers in order to invoke a sense of viral “sharing.” Kha was selected by up-and-coming photographer Bridget Collins, whose clean-hewn environmental work provides an interesting contrast to Kha’s dense portraiture.

Collins chose Unity, a photograph of Kha’s in which a young, Asian woman, carefully made up, lies stomach down on a poster. The woman’s parted lips and glassy eyes exactly mirror those of the model on the poster. Both the model and her imitator gaze placidly at a point in the distance. This photo is from Kha’s most recent series, “A Real Imitation,” work that builds upon his previous collection, “This Graceland.”

As might be guessed from its “Graceland” title, Kha’s photography is largely set in Memphis. It takes place in the back rooms and storefronts of the city. Kha’s subjects pose amid flaking wallpaper and broken air-conditioning units. They wear maroon bathrobes in rooms full of packed boxes. These photographs seem drawn from a lost era, given that those “lost eras” never really existed but are the stuff of film and fiction. Kha’s scenes are cinematic: dramatically lit, pale, feathery, contrastive, or stark as needed.

But Kha is no nostalgia artist; he is a portrait photographer with a critical lens. His subjects seem to be in a lost world — an old Memphis — but they are not quite of it. Often, they gaze off into the distance, past their location and past the camera itself. They look into the source of the light.

Kha is well-versed in light. He cites William Eggleston as an influence, as well as German photographer Wolfgang Tillman, whose works include a retrospective simply called “Lighter.” When Kha moved from Memphis to go to Yale, he studied under Philip-Lorca diCorcia, the preeminent contemporary photographer and progenitor of the “staged” photograph. DiCorcia is a master of the scenographic photo, a feat that depends heavily on manipulated lighting.

Kha’s photographs show this education, as well as something of his own past growing up in a Memphis of neon lounge lights and white lace curtains. He says that even when making work outside of Memphis, he has been schooled in the South’s “visual cues.”

These cues have led him to make work that not only pays material tribute to Memphis (in the form of a wrought-iron window grate here or a canary-yellow chair there) but that heeds a Southern awareness of race, gender, class, and appearance. Kha’s early works, “Return to Sender,” “American Knees,” and “What’s My Line?” all directly address race.

For the “Return to Sender” series, Kha asked strangers to kiss him while he refused to kiss back. Besides being visually arresting photography, “Return to Sender” makes a clear point about perceptions of Asian men as passive sexually. For “American Knees,” Kha dresses up in yellow face. For “What’s My Line?,” he assumes costumes of different stereotypically appropriate careers for a young man of Asian heritage.

Kha credits photographer Diane Arbus with teaching him about “distinct levels of difference.” Where, in earlier work, Kha took up a more direct conversation about identity, his recent photography has a layering that is both visually literal and critically thorough. It is also mysterious, a quality that Kha uses to high effect.

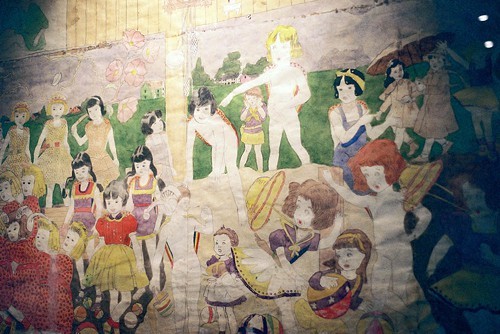

Difference, in the “A Real Imitation” series, is played out through mirroring. Kha uses his adept sense of light to focus on one of light’s most salient effects: reflection. In the black of old TV screens, in aluminum foil, in windows and in mirrors, Kha’s subjects are subtly reflected. Or else they stand with someone else who is both a reflection and a grotesquerie of a reflection, as in one photo, where Kha (his own subject) stands half-naked next to a man several feet taller than him. They hold hands. They both wear black socks. They don’t look at each other.

The conversation on bodies, race, and sexuality is unavoidable in Kha’s work. The work is clearly about difference. But it is also about the subjects of difference. It is left for the viewer to ask what role the portrayed play in the world they inhabit.