Sofia Gonzales* had just gotten off a long shift at her weekend job when we met for coffee on a recent evening. The young woman, who carried herself with the confidence of a senior class president, was dressed in her work uniform: a T-shirt and black, bell-bottom pants. Despite being tired from work, Sofia introduced herself energetically, directing my attention to her feet. She explained, as she adjusted the fabric where it flared around her ankle, that she wore these pants for practical reasons. The loose fabric concealed a heavy, black device wrapped around her ankle. In Spanish, she called the device her grillete — or, in English, her “shackle.”

“I feel embarrassed,” Sofia told me through a translator, gesturing toward the plastic ankle bracelet. “This makes me feel like a delinquent. People look at me like I am a criminal.”

Sofia has no criminal record, neither in America nor in her Central American home country. She is a recent immigrant to the United States and is currently seeking asylum from violence that has affected her family. She wears the device, a GPS tracking bracelet, as a part of a controversial immigration initiative known as the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program. She wears the monitor 24/7, including when she sleeps and when she showers. Sofia is one of 178 adults and juveniles in Memphis, and of 497 in Tennessee, and almost 50,000 nationally who wear GPS ankle monitors. None of those wearing the shackles are considered criminal risks by the U.S. government.

From outward appearances, Sofia’s life seems like that of a well-balanced 20-something. She has a job and legal authorization to work. She lives with a few family members in Memphis and enjoys playing sports, though her participation is hindered by the half-pound monitor. She is learning English.

Despite having to charge the monitor for several hours a day, which requires her to tether herself to an electrical outlet, she is able to lead a semi-normal existence. She says that she feels like, even though she has only been in Memphis for a short time, she has already accomplished a lot.

But, like many undocumented individuals, Sofia is afraid that she will be sent back to a dangerous city in her home country where she is under threat of violence and where her relatives have been killed. She says that she wants to go by the rules here, that she has been fastidious about following immigration restrictions and guidelines. But while her case hangs in the balance, she is subject to what she, and others in her situation, see as a demanding, confusing, and unfair surveillance program.

“Why would I run away?” asked Sofia. “I don’t understand. I have done everything they asked. I want to be here.”

A Big Business

The 24/7 GPS monitoring of undocumented individuals is still a relatively new feature of the immigration system. The program was introduced in 2004 by Immigrations Customs and Enforcement (ICE) as a way to monitor and control the movement of immigrants who the government determines have no right to be in the country, but who, for any number of reasons, are not detained. Many are women and children. Since its inception a decade ago, the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program (ISAP) has expanded by tens of thousands of participants. It is promoted by ICE as an “alternative to detention.”

Advocates for the supervision program point out that GPS monitoring bracelets have the potential to be more humane, especially for juveniles and caregivers, than federal detention.

They also point out that the program saves the government money. According to ICE, the average daily cost per ISAP participant is $4.45, whereas detention can cost the government over $150 a day per participant.

But the program has come under fire from human rights advocates — including groups such as the Women’s Refugee Commission, Detention Watch Network, and, locally, Latino Memphis — who see it as offering a wrongheaded “solution” to something that was not a problem in the first place. Asylum-seekers such as Sofia, according to advocates, are not what ICE refers to as “flight risks” and do not deserve 24/7 surveillance. Critics argue that ISAP exists not for security, but for intimidation and private profit.

The GPS supervision of migrants is big business and getting bigger every year.

ISAP makes millions of dollars each year for the private contractor, GEO Group, that provides and monitors the bracelets. GEO Group is, according to their latest financial report, “the sixth-largest correctional system in the U.S. … including the federal government and all 50 states.”

In 2015 GEO Group’s total revenues were roughly $1.8 billion dollars. ISAP is one of its biggest contracts. GEO Care, the GEO Group subsidiary that operates ISAP, made more than $302 million for the company in 2015. ISAP is operated by a GEO Care subcontractor called BI, which stands for “Behavioral Interventions.”

Critics say that the profitability of the tracking program creates incentive to expand the program, which criminalizes asylum seekers. They also maintain that the way the program operates — locally, in Memphis, and nationally — can be opaque and even unconstitutional.

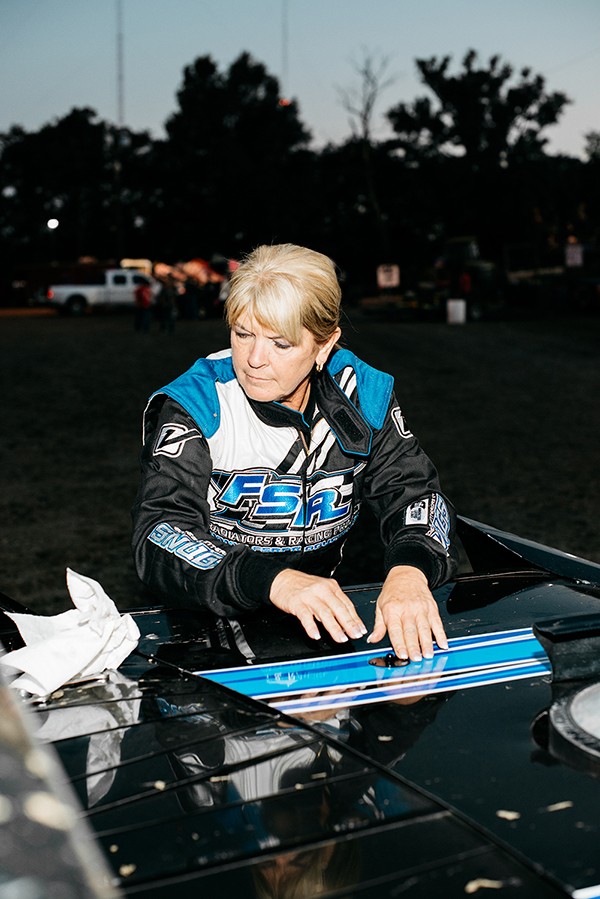

Casey Bryant, an immigration lawyer with Latino Memphis, sits for a portrait in Memphis.

Casey Bryant, an immigration lawyer with Latino Memphis, says, “They say they are helping, but they are actually just violating people’s human rights and trying to redistribute costs to immigrant families. In effect, immigrant, undocumented families are paying for other family members’ detention.”

Watched Women

Ana Ramirez* first came to the United States in the mid-2000s. A young refugee from a war-torn state, Ana has lived without papers almost her whole life. She lived and worked as a domestic employee in an abusive situation in Mexico before migrating to the states. She now has school-aged American-citizen children. Her husband, also an undocumented immigrant, is the sole provider for her and the children.

A year ago, Ana left the states to see family in Mexico and attempted to return. Upon her re-entry, she was detained and released with an ankle monitor. She was told by ICE that ISAP was optional, but if she declined the ankle monitor she could be detained.

“When I first came to the country, I walked in the desert for three days and nights to get here. I felt free,” Ana says. “Now, with the grillete, I feel like a prisoner. I feel ashamed. I don’t leave my house.”

Ana’s story is similar to the other four women who agreed to be interviewed for this article, all of whom requested to remain anonymous for fear of negative ramifications to their immigration cases. Compared to the younger Sofia, Ana has less mobility or agency. She has no means of regular transportation and cannot work. She is waiting for what’s known as a “credible fear interview,” which would establish in court that she has legitimate reason to fear a return to her home country.

A survivor of domestic abuse, Ana — and other women like her — is in a vulnerable position. She cannot speak English, and, though she has applied for work authorization, the stringent measures of ISAP would keep her from having a weekday job. She depends on her husband for transportation and support.

Unlike many, Ana does have legal counsel. She sought out a lawyer after an ICE officer told her, during a check-in, that she had to buy a plane ticket back to the country where she was born. When she said she did not have enough money to buy the ticket, she was told by ICE to go to a church and ask for charity. “I was scared,” Ana said. “I was confused.”

Since then, Ana’s lawyer has fought to get her case back into immigration court, where Ana could be granted asylum. In the meantime, Ana wears the monitor, which causes her headaches, and is often hot and uncomfortable around her leg. She says that the monitor is a source of constant stress.

But when asked whether, if she’d known she would be monitored, it would have dissuaded her from coming into the country to be with her children and husband, Ana’s answer is simple: “No.”

An Unclear System

Like all the women interviewed for this story, Ana does not know how or why her schedule of in-person check-ins is determined. She also does not know why she was selected for monitoring, when others with her same immigration status do not wear the monitors. She does not know when or if it will ever be removed.

A spokesperson for ICE told the Flyer that “when determining whether or not an individual should be enrolled in the ISAP program, numerous factors are considered on a case-by-case basis. These factors include, but are not limited to: current immigration status, criminal history, compliance history, community or family ties, being a caregiver or provider, and other humanitarian considerations.” Each person’s specific requirements under ISAP are also determined on a case-by-case basis.

Ana has a particularly stringent regime of check-ins: Once a week, her husband takes her to the immigration office to see her assigned ICE officer, a process that can take between one and seven hours. Also once a week, on another day, a representative from the private security contractor visits her at home. The contractor searches her home, though Ana has not been told why.

Ana’s lawyer is concerned about the legitimacy of the home searches.

“They have no warrant to search her home,” says her lawyer, whose name is withheld to preserve Ana’s anonymity. “But they are working under ICE, and ICE is getting away with violating their constitutional rights. But then when you go and complain, ICE tells you, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, this is in lieu of being detained.’ Well that doesn’t leave us with a lot of room to argue because we don’t want that for them, and they don’t want that for themselves. It is a hard case to make.”

Two of the four immigrant women interviewed for this story also reported that their homes had been searched. Another woman, Elena Vargas,* said that the private contractor told her that she was a social worker when she came to her house. “She said she was a social worker,” Elena said, “but I knew she was not a social worker.”

When asked whether these searches were protocol, representatives from BI and ICE did not comment.

Once, when Ana was on her way to see her lawyer, a BI employee called and asked her where she was going. She felt intimidated. Said Ana’s lawyer of the incident, “They are watching them very, very closely.”

Bryant said that she had a client who’d been in the country for months and was called into the ICE office on routine business. There, her client was, without warning, given one of the monitors. Bryant said that she has had difficulty interacting with representatives from BI on behalf of her clients and was told that BI case managers “don’t speak to lawyers.” When Bryant asked the case manager direct questions, the contractor avoided eye contact and spoke only to Bryant’s client.

Said Bryant, “A lot of people have no idea why they got [the monitor.] They say, ‘They basically just slapped it on me.’ And, you know, you don’t just slap someone in jail. You don’t just throw them in there and not tell them why.”

A History of Alternatives

The idea for alternatives to detention is nothing new, but the idea that those alternatives should involve 24/7 surveillance is something that emerged after 9/11, with the genesis of the Department of Homeland Security. Alternatives to detention (ATD) programs have grown and changed alongside greatly expanded immigrant detention programs.

Before 1996, the only non-citizens detained were those considered by the government to be a flight risk or a security threat. There were fewer than 10,000 beds reserved for detained immigrants in facilities around the country. There are now more than 30,000 beds in facilities across the country, many of them in private facilities operated by GEO and another private corrections company, Corrections Corporation of America.

Alternatives to detention programs have changed from focusing on social work to focusing on surveillance.

A 2012 report by the Rutgers School of Law-Newark Immigrant Rights Clinic, in conjunction with the American Friends Service Committee, contrasts the current iteration of ISAP with a pre-9/11 alternative, the Appearance Assistance Program, run by a group called the Vera Institute of Justice:

“The program was intended as a true alternative to detention, in that the Vera Institute screened detained immigrants in New York and New Jersey to determine eligibility for release from detention and acceptance into the program. The program assessed its 500 participants individually to determine the best methods of supervision in order to ensure appearance for court hearings and compliance with removal orders …

Over the course of three years, the Vera pilot program reportedly saved the federal government an estimated $4,000 per individual participant. Beyond being cost-effective, the AAP showed remarkable success in its goal of ensuring attendance at hearings.”

The Vera Institute’s program was aimed at making sure non-citizens met their court requirements. It did so successfully, without the need for surveillance, but surveillance by for-profit companies is becoming the norm in the international migration industry.

In an interview, Michael Flynn, executive director of the Global Detention Project, commented on the expansion of surveillance programs: “There is clearly and has been for the past 30 years an increase across the globe in using enhanced technology to ‘manage migration effectively.’ It runs the gamut from evasive and harsh practices such as ankle bracelets to things like exchanging databases across countries so that they can better identify people. This involves a lot of outsourcing [to private companies.] I’m not an anti-privatization activist, but one does have to wonder whether or not these practices are encouraged by companies that have something to gain.”

Elena Vargas says that, because of the monitor, she is ashamed to leave her house.

An Endgame

All four women interviewed for this story expressed that, while the physical and time requirements of being monitored are burdensome, the hardest thing for them is the stigma of wearing the monitor.

“People look at me like I have murdered someone,” Elena said. “I don’t want to go to the hospital when I am sick, or to the grocery store.”

The women feel intimidated and confused — something that, according to immigrant rights advocates, seems to be part of the point. They cite the opaqueness of ISAP as part of what makes it intimidating.

The 2012 Rutgers report on ISAP highlighted a number of flaws in the program, including ICE officers’ lack of “clear and up-to-date” guidelines, a lack of a public and standardized assessment tool for who participates in the program, a lack of consistency, and the inhumanity of constant supervision. Rutgers put forth suggestions for more community-based models as well as greater transparency on the part of ICE.

Those suggestions have not been answered, either nationally or in Memphis. Meanwhile, since 2012, the number of men, women, and children enrolled in the 24/7 GPS supervision program has grown by 20,000. Sofia, Elena, Ana, as well as their children and families, wait to find out what will happen to them.

“I feel like this is pointless,” Sofia said. “I could cut it off. I could run. But I don’t want to. So why are they doing this? It’s overdone. We get it. We are not supposed to be here.”

*Names, details, and photos were edited to protect the identities of individuals in this story.

Kurt Pershke, RedBall Project in Paris

Kurt Pershke, RedBall Project in Paris