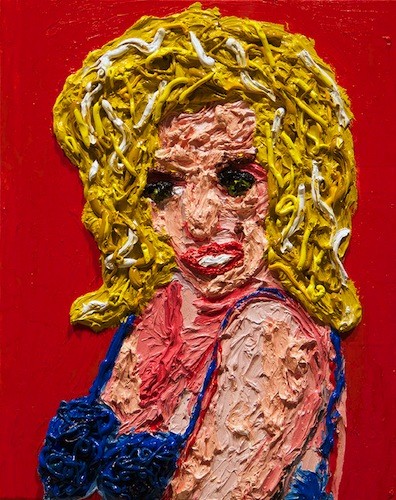

Over the course of the past five months, artists Tad Lauritzen Wright and Hamlett Dobbins have painted about 50 heads. The heads, which currently animate the walls of Lauritzen Wright’s Midtown garage/studio, are made from neon-colored paper and googly eyes. They are not accompanied by bodies. They are heads in the same way that Muppets are animals, which is to say that they are more head-like than they are like anything else, but you couldn’t exactly call them naturalistic.

These recent works from Lauritzen Wright and Dobbins are only the latest effort in the artists’ longtime collaborations. This Friday, Glitch will host the fifth show of the friends’ work together — an exhibition they titled “Born to Hula” after a beloved Queens of the Stone Age anthem. The paintings in “Born to Hula” are a departure from the artists’ earlier collaborations because, where past works have been compiled over long periods via mail, Lauritzen Wright and Dobbins made these pieces working together in the same room, one morning per week.

“I drop my kids off and he drops his kid off and we work,” Lauritzen Wright told me when I visited his studio to see Dobbins’ and his preparations for the show. “One of the titles we were thinking about for the show was ‘Daddy Daycare.'”

What transpires at Daddy Daycare, according to Dobbins, is a kind of “nonverbal conversation.” Paintings are passed back and forth, metal albums are played, pieces are added to or reduced to parts for other paintings. “We come in,” says Dobbins, “and we make these marks and we make these moves and maybe at the end of the day, we will talk about it. It is this nice kind of way of thinking about things.”

The garage studio where Lauritzen Wright and Dobbins work is crowded with liquid acrylics and dirty brushes, torn or otherwise dissembled sheets of paper, half-formed drawings, and glittery material tests. There are also several works attributable to Lauritzen-Wright’s 6-year-old daughter, who the artist cites as one of his major current influences.

“I have a 6 year old and I put a lot of stuff up of hers and she plays out here a lot … but that is kind of where my aesthetic falls at the same time,” says Lauritzen Wright. “I knew my aesthetic was child-like,” he laughs, “but I didn’t know what exact age it was like until my daughter got to be 5 or 6.”

The aesthetic in “Born to Hula” is child-like: monstrous and colorful and plasticky like recycled toys. The “dopey and fun” paintings (as Dobbins calls them) champion a kind of infinitely bright 1970s boyhood held in infinite backyards. But there is also a twist of jaded junkiness in the yet-untitled works, such as the one they describe as “the mush painting with a see-through rainbow on it.” In the paintings’ dark moments, we are reminded that even pristine pre-fab swingsets must one day rust.

The artists often work at a large scale and quickly, without preciousness about past creations. “I make these big oval-shaped paintings and drawings,” Dobbins says. “Sometimes those don’t work, though, and when those don’t work, I just sort of grab four of them and stitch them together. We realized that it would be better if we cut it out and there was this kind of X shape … I have been piling colors on.”

Lauritzen Wright says, “I kind of dig the heads out of abstractions, and then [Hamlett] is digging them out through cutting. Most recently, on some of the larger ones, Hamlett had some really simple linework, and then I went in and kind of accentuated his line. We were really happy with those. It pushes and pulls in both places.”

It will be interesting to see Dobbins’ and Lauritzen Wright’s work at Glitch, Adam Farmer’s house gallery that has, over the course of the past year, hosted Memphis’ most dynamic collaborative shows. Farmer’s space is also casually nostalgic, though for a caffeinated ’90s (Air Bud! Tim Allen!) rather than Dobbins and Lauritzen Wright’s open-hearted ’70s.

Even without the liberal use of googly eyes, Lauritzen Wright and Dobbins collaboration would feel not-too-serious and warm. “Hamlett is the best painter I have ever known,” says Lauritzen Wright, “and the way he goes about using paints has been really interesting. There has been a lot of attention paid to how things look on the surface.”