The recruiting of high school basketball players to Division I college programs is like a big live-theatre show, often with an unpredictable ending. Regardless of the production, the five principal characters are the same: The recruit; the high school coach; the parent/guardian; the college coach; and the summer league coach.

Josh Pastner

I interviewed five people, each representing one of the characters in the recruiting process. I asked each the same set of questions. Their answers represent their own experiences. Others in similar positions may agree or disagree with the positions they have taken. Here are my “starting five.”

Jordan Varnado

1) The recruit. Jordan Varnado is a senior at Haywood High School in Brownsville, Tennessee. He’s the brother of former Mississippi State center Jarvis Varnado, who played in the NBA last season. The younger Varnado is currently being recruited by numerous “mid-major” schools. He was also being recruited by Auburn, prior to the firing of former coach Tony Barbee, and Ole Miss coach Andy Kennedy, who later cooled on Varnado. He played AAU basketball with Team Thad this past summer.

2) The college coach. Memphis Tigers coach Josh Pastner has the reputation of being one of the best recruiters in the nation. He has landed notable top-ranked recruits such as Will Barton, Joe Jackson, Shaq Goodwin, and Pookie Powell. By NCAA rules he can not talk specifically about a recruit who has not signed a national letter-of-intent.

3) The parent(s) or guardian. We interviewed Chris Chiozza, father of former White Station guard Chris Xavier Chiozza, who is now a freshman point guard at Florida. The former Spartan also played AAU basketball with Team Thad in 2013 before becoming a Gator.

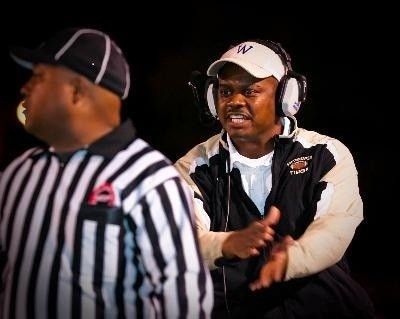

4) The high school coach. Longtime Memphis high school coach Ted Anderson is currently coaching a big-time Division I prospect in LeGerald Vick at Douglass High. The former Hamilton coach has coached several players who have gone on to play in some of the top programs in the nation, including Todd Day (Arkansas), Billy Richmond (Vanderbilt, Memphis), and Shawne Williams (Memphis).

5) The summer coach. Norton Hurd coaches Team Thad 17 & under squad. His 2014 team went 7-0 in Panama City, Florida, winning the Gulf Coast Challenge. Varnado, Vick, & Chiozza have played for him.

Q&A

What do you like and dislike about the recruiting process?

Varnado: I like that (college) coaches get to know you and you get to know them. The bad, if you have a bad game they just move on to other players.

Pastner: Evaluating, finding out if someone is good enough to fit your program. Is he a good fit, on and off the court? Finding out who is part of the decision-making process. It is important to know when to get out and understand when you are wasting your time.

Chiozza: (College) coaches can not talk to players until after their sophomore year in school and that’s good. It keeps the kid hungry and working hard. But it wouldn’t be bad to have a limited number of times (college) coaches could talk with parents early in the process.

Anderson: Dislike about it at this point? I’ve seen it from a lot of angles. The colleges are recruiting the high school athletes more through the summer or AAU coaches and I think it’s a travesty. Sometimes that (summer) coach has his hand out to steer that kid to a particular school. The high school coach has nurtured the guy and then the AAU coach gets in and muddies the picture. Sometimes its counter to what the high school coach has done.

Hurd: I like that a kid who has worked all his life will have a chance. A lot of the kids will be the first in their family to go to college. Now some kids will have a lot of offers. It’s a lot of work trying to find the right fit for him. I don’t hate it, but it could be draining for a coach and a player.

How involved should the recruit’s (summer) AAU coach be?

Varnado: Very involved. He’s the one that helped you get exposure.

Pastner: All coaches are very important. Their input is part of the process, as long as the coach has the best interest of the kid.

Chiozza: Just depends on the player and what type of parental support he has.

Anderson: The biggest thing with AAU is travel and exposure. If (the recruit) is on an AAU team, he’s already a good player. The exposure is the key thing. That’s why I encourage my kids to play AAU. So the AAU coach should be involved, but a lot of them are young and not as experienced.. Now some college coaches recruit strictly through AAU. College coaches will seek whoever has the most influence on the player. If the player’s dog was involved and had the biggest influence, the coach would be hanging around the dog. They don’t give a damn.

Hurd: Depends on the situation. Depends on that family. Some parents lean more on an AAU coach. Some lean more on the high school coach. It depends on the relationship the kid has with the coach.

How involved should the recruit’s high school coach be?

Varnado: He’s the contact. The college coach will contact (high school coaches) and ask questions about how you are as a person, and a man. He’s been with you for four years. He’s the guy to get you to the next level, so he should be very involved.

Pastner: Same deal as the summer coach. High school coaches are crucial, a very important part of the process.

Chiozza: About the same as the AAU coach. But it seems like we (his son, Chris Chiozza) had a lot of support with our high school coach. But most AAU coaches seem to be stepping up.

Anderson: Really, really involved. (The high school coach) has experience. He knows NCAA rules. He has experience with college coaches. Parents and kids don’t always know NCAA rules. But he should be a facilitator and not a decision maker.

Hurd: There’s no right answer. I’ve worked hand-in-hand with (White Station coach) Jesus Patino, for example. These days a lot of offers come during the summer while the player is with the AAU team. But as long as it’s a positive experience and it’s all good for the kid, that’s the bottom line. At the end of the day, it’s about the kid. I don’t care if I have no say so in the matter, as long as the kid is happy.

How often should the recruit hear from the college coach?

Varnado: Once or twice a week.

Pastner: Depends on the individual. Some want to hear from you every day. And I’ll say this, you are only allowed so much time to see the recruit and you always want more time to evaluate him, get to know him.

Chiozza: I think it would be fine to hear from him once a day. I don’t think a (college) coach needs to text five, 10, 20 times a day.

Anderson: These college coaches are trying to keep their jobs. A college coach once told me he looks at a kid and then will ask himself, “Can he put food on my table?” Now there are guidelines for it. If I were a college coach, I’d call as much as possible, if you are looking at it from his vantage point. If I’m a parent I would say the (college) coach is calling too much. Listen, kids at first like all the attention. After a while it becomes a bore. All that sh*t starts to run together. It gets old.

Hurd: If (the recruit) is a senior in high school, I think it’s unlimited. The higher the grade the more access a coach should have as the kid tries to make a decision.

Do college coaches put too much pressure on the recruit?

Varnado: Not necessarily. Depends on how the recruit feels about the school. A (college) coach can’t make you do what you don’t want to do.

Pastner: No, I don’t think so at all. It’s just all part of the process.

Chiozza: Tough question. I know some want to tell you whatever you want to hear. I guess it depends on how much the kids’ parents are involved in helping them through the process.

Anderson: No, I don’t think so. Now if a (college coach) could move in next door to a player they would. But all they really want to do is show kids they are interested in them.

Hurd: Some (college) coaches do. It depends on the coach’s style. I understand it from both perspectives. Sometimes a kid commits too early. Some want to wait and that puts the (college) coach in a tough position if they have someone else they are looking at in the same position.

Whose opinion does a recruit value most?

Varnado: The parents. My parents have helped me out a lot, my family too, also the college coach because he’s the one that’s going to put you on the court.

Pastner: Each situation is different. It totally depends on the situation.

Chiozza: I think probably their AAU coach the majority of the time.

Anderson: I think a lot of them value their high school coach. The relationship between a high school coach and player is unique. Once you leave high school it becomes more and more of a business.

Hurd: Depends on the situation. Whoever the kid is more comfortable with. And the college coach will recognize this and go after the person who has the most influence on the kid.

What should a parent’s or guardian’s role be?

Varnado: Support their kids. Ask questions. Ask what he wants to major in. As him how will this or that school help him develop as a man.

Pastner: You want them to be involved. But sometimes they are not as experienced and will defer to the AAU or summer coach.

Chiozza: They should be there for every step. The more they are involved the better for the kid. The parents will always have the kids’ best interest.

Anderson: Parents should have some weight too. They should be the second voice. Players first. Third is the high school coach. The AAU coach next. Now the AAU coaches I deal with have been right on the spot, deferring college coaches to me.

Hurd: At the end of the day, it’s your kid and the parent should be very involved. But if they are not comfortable with the process ask for advice.

How important is academics in the process?

Varnado: Very important. You want to go to a school that will help you be successful after basketball. You’re going to have to hit the books hard in college. You can’t slack off.

Pastner: Very important since it’s about education.

Chiozza: If you are not a top 50 or 100 recruit it’s huge. I think it’s big because (college) coaches don’t want to deal with getting players eligible. They are more likely to recruit kids who make the grades.

Anderson: It’s the second biggest piece in the process. The first piece is if the kid can play, because if he can’t play they don’t care if he’s an honor student. It’s the second thing a college coach asks, “What are his grades like?” You short change a kid if you don’t concern yourself with his education.

Hurd: If he doesn’t qualify he doesn’t go to college. And after basketball you are going to need your education. Location is important too. Because sometimes the city where you attend college will give you more opportunities than any other place after you are done with college.

What is a recruit looking to find out during his campus visit?

Varnado: Looking to find out how loyal the coach will be. How will the school be able to help after basketball or whatever sport he players.

Chiozza: He’s looking to meet his possible teammates and find out how he will get along with them. He’s looking at the campus diversity, location and proximity to home, how he will get along with the coaches.

Anderson: He wants to know if the facilities are huge, if he has a nice house to play in. Is he eating good? They want to know how the team travel, by yellow bus or jetting in, and how many games are on t.v.

Hurd: How nice is the city? Will they have access to the facilities? What’s the coaching style like? They get to how coaches run practices and get an idea of what their role will be. They want to find out what they will major in.

So what would you like to see changed with recruiting?

Varnado: When you have a bad game, coaches stop recruiting you. They need to see you more. Ole Miss was interested in me at some point, but then suddenly nothing, after one bad game.

Pastner: There’s always going to be an evaluation of the rules. But the rules have gotten better. Things can be tweaked. But overall it’s better today than it has been.

Chiozza: I think it would probably be more beneficial if the college coaches could come out more. See the kid more. That puts a lot of pressure on a young man when you have to perform knowing a coach is watching you. If the (college) coach could come out and see the kid more often, it would put a lot less stress on (the recruit).

Anderson: Most recruits already know where they want to go. Not that it’s a problem, but if the number of visits were changed, that could be something. There could be fewer visits (from college coaches) but I’m not campaigning for it to be that way and it’s fine the way it is, but if I had to change something that would probably be it.

Hurd: I think it’s set up pretty fair. But maybe the college coaches could come out and see the kids more.

You can follow Jamie Griffin on twitter @flyerpreps