Pawtuckets

In the early ’90s Mark Edgar Stuart, then a college student on an orchestra scholarship, picked up a copy of the Flyer, read an ad, and joined a band. “I was reading the Memphis Flyer one day, and there was an ad in the classifieds, ‘bass player wanted,’” Stuart says. “I never in a million years would I have answered a bass player wanted ad, except it said ‘influences — the Band and Blue Mountain.’” Stuart, who had expected to see a list of cheesy metal bands, says his interest was piqued. The ’90s alt-country movement hadn’t really gotten off the ground yet, but Blue Mountain was making some waves in Oxford — and of course Stuart knew the Band. “I called the number” Stuart says. “I wasn’t even interested in being in a band. It’s just one of those serendipitous things.” Thus began the career of the Pawtuckets, who will reunite after 18 years this Saturday to headline the Madjack Records 20th anniversary concert at Railgarten.

The beginnings of the Pawtuckets are relevant (beyond providing proof of the merits of regularly checking out the Flyer) because the Pawtuckets, and Stuart, are inextricably tied to the history of Madjack Records.

“Around 1998, with our second record, [Rest of Our Days], we decided to start a record label,” Stuart says. “It didn’t really mean much at the time. … It was just a vehicle to put out the Pawtuckets record.” With Stuart on bass and Kevin Cubbins handling guitar and pedal steel duties, the Pawtuckets were helmed by the dual songwriting talents of guitarist Mark McKinney and pianist/guitarist Andy Grooms. Percussion was handled by a rotating cast of drummers. “McKinney had a dog named Madison, and Andy Grooms had a dog named Jackpot,” Stuart remembers. “So we said let’s just name the label Madjack after the two dogs.”

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon

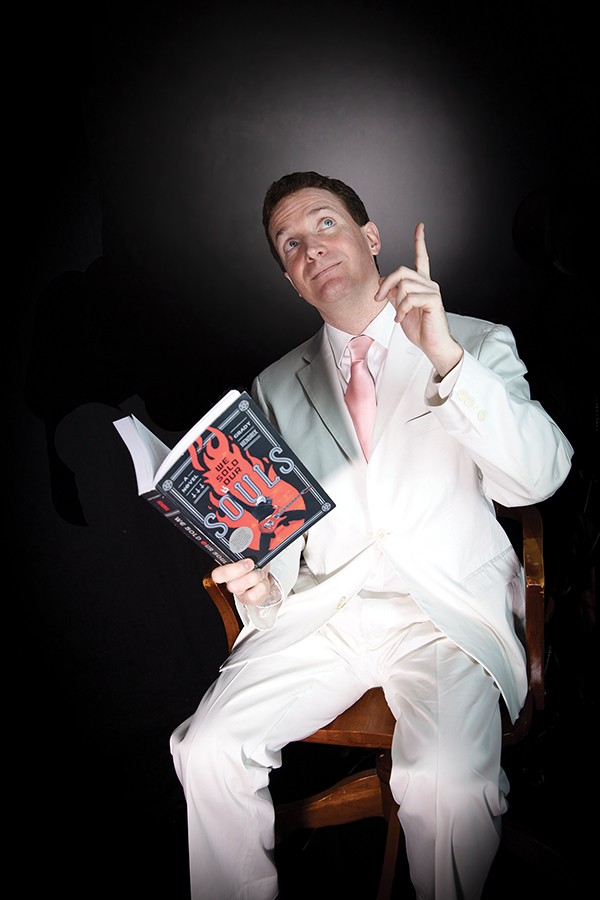

Mark Edgar Stuart

Though Stuart confesses to being more interested, at the time, in playing bass and drinking beer than in business, he says McKinney had bigger ideas and took a more serious interest in Madjack. Before too long, Madjack had signed Cory Branan and Lucero, a band the Pawtuckets often shared bills with. Co-owner Ronny Russell joined the Madjack scene to help McKinney with the business side of things. Says Stuart, “It just sprouted wings after that.”

Joshua Black-Wilkins

Joshua Black-Wilkins

Cory Branan

Eventually the Pawtuckets disbanded, but Madjack soldiered on. The label continued to grow and to represent Memphis talent, through the CD boom, after the advent of the downloadable mp3, into the age of online streaming. “We definitely had to evolve,” Russell says. And still Madjack has signed Memphis artists like James and the Ultrasounds, Susan Marshall, and Jana Misener, up to and including Stuart’s recently released third album, Mad at Love, recorded in part at Scott Bomar’s Electraphonic Recording studio in Memphis and in part with Bruce Watson of Fat Possum in Mississippi.

Susan Marshall

Stuart, who began his Memphis music career playing upright bass in an orchestra pit, has transformed again in the past few years with the growth of an unexpected singer/songwriter career. “I just started the singer/songwriter thing about six years ago,” Stuart says. “Up until that point I was just a bass player. I played for the Pawtuckets and Cory [Branan], Alvin Youngblood Hart, and just whoever needed a bass player,” Stuart says, listing an impressive curriculum vitae. He adds two more Memphis heavy hitters: Jack Oblivian and John Paul Keith.

“If you’d told me 10 years ago I’d be doing what I’m doing now, I would have told you you were crazy,” Stuart says. “Then in about 2011, I got cancer and lost my dad and it just inspired me to try to do something different.” Stuart says he felt like he had something to write about and a more mature viewpoint to bring to his craft. Around this time, with his 2013 debut solo LP, Blues for Lou, Stuart first pinged my radar. I remember hearing “Remote Control” on the radio, and pulling over to the side of the road to listen. I imagine I’m not the only one who’s been so affected by Stuart’s powerful songwriting. Stuart will perform his solo material at the anniversary show in two sets — a full band set and a stripped-down songwriter set — as well as joining Jana Misener and Krista Wroten-Combest and the Pawtuckets on bass.

James & the Ultrasounds

“I never thought [the Pawtuckets] would get back together, but this seemed like the perfect moment,” Stuart says of the Pawtuckets reunion show set to close out the festivities at the Madjack anniversary shindig Saturday. “We haven’t played together since 2000, and we haven’t played with the original drummer since 1998, so it has been 20 years since we played with the original lineup.” With the Pawtuckets reunion concert and brand-new and soon-to-be-released albums from several of the artists in the Madjack arsenal, the anniversary show should present a mix of old and new sounds from the Memphis label.

Madjack Records celebrates 20 years at Railgarten Saturday, October 20th, at 1 p.m. Free.

Lineup:

Wampus Cats – Outdoor Stage – 1:00 – 2:00p

Jed Zimmerman – Outdoor Stage – 2:00 – 2:45p

Corduroy & the Cottonwoods – Pong Bar – 2:45 – 3:30p

Keith Sykes – Outdoor Stage – 3:00 – 3:45p

Delta Joe Sanders – Pong Bar – 3:45 – 4:30p

Mark Edgar Stuart (solo) – Outdoor Stage – 4:00 – 4:45p

Rob Jungklas – Pong Bar – 4:45 – 5:30p

James & the Ultrasounds – Outdoor Stage – 5:00 – 5:45p

Eric & Andy – Pong Bar – 5:45 – 6:30p

Susan Marshall – Outdoor Stage – 6:00 – 6:45p

TN Boltsmokers – Pong Bar – 6:30 – 7:15p

McKenna Bray – Outdoor Stage – 6:45 – 7:30p

Mark Edgar Stuart (band) – Pong Bar – 7:45 – 8:45p

Jana & Krista of Memphis Dawls – Outdoor Stage – 8:00 – 8:45p

Cory Branan – Outdoor Stage – 9:00 – 10:00p

Pawtuckets – Pong Bar – 10:00 – 11:00p

Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis  Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis  Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis  Jesse Davis

Jesse Davis

Allison Green

Allison Green

Jasmine Hirst

Jasmine Hirst

Samantha Smith

Samantha Smith

DBW Photography

DBW Photography