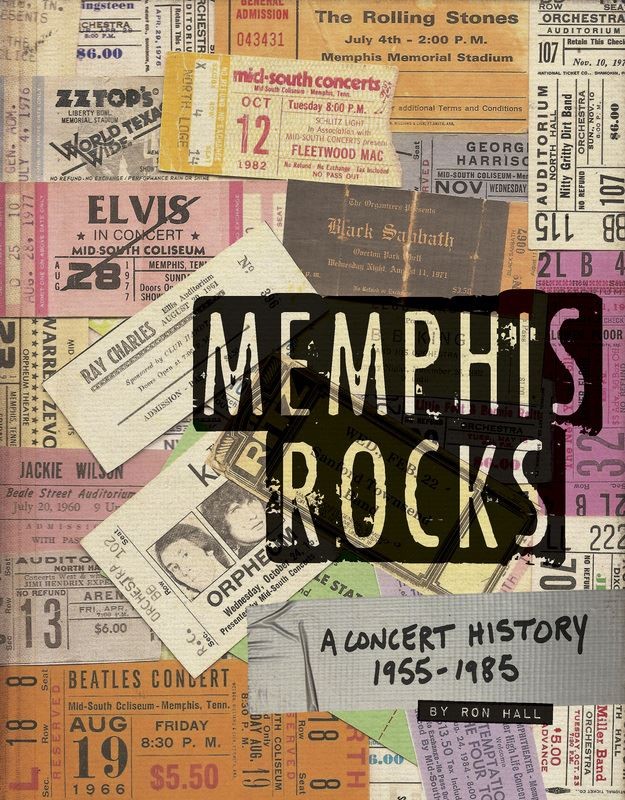

“This guy worked with Zeppelin and now he’s yelling at me,” thought Landon Moore, guitarist for American Fiction, a Memphis band celebrating the vinyl release of its debut album at Lafayette’s on Tuesday, November 25th. That record, Dumb Luck, was produced and engineered by Eddie Kramer, the renowned recording engineer who engineered the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, and the Rolling Stones at Olympic Studios in London, as well as Led Zeppelin, more Hendrix, and David Bowie in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

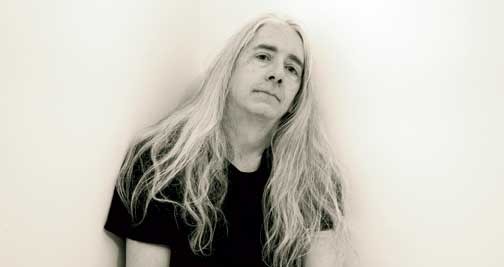

The title has something to it. American Fiction is composed of seasoned Memphis musicians: Chris Johnson (Ingram Hill), Blake Rhea (the Gamble Brothers, CYC), Landon Moore (Fast Planet, Patrick Dodd Band), and musically promiscuous jazz pianist Pat Fusco. Peewee Jackson recently replaced Zach Logan on drums.

On a lark, they sent a demo to Kramer’s email address. Why not?

“The genesis of the story is this,” Kramer said last spring during a break from tracking the record at Ardent Studios with engineers Jeff Powell and Lucas Peterson. “There’s a lot of stuff that comes to my computer. Very fortunately, my better half was scrolling through some of the stuff [and said] ‘Honey, This is pretty good. Come check it out.’ I listened to it, just the first few bars of what Chris had sent. I said, ‘That’s pretty damn good.’ I went through the whole thing and got very interested with his voice and what he had sent. So I called him up. He almost had a heart attack and needed several pairs of Depends and all the rest.”

Upon learning that they would work with one of rock’s best engineers, Fusco told Moore, who usually plays bass, “You realize the first time you play guitar in front of anybody, it’s going to be a dude that cut Hendrix, Zeppelin, the Beatles, the Stones, Traffic.” No pressure. Fortunately, Kramer has a wicked sense of humor and knows talent when he hears it.

“It was fun,” Kramer said. “I really liked the songs, and I liked what he was trying to do and what the band was trying to do. It’s not often that I hear something right off the bat that I instinctively go to. It’s happened a few times, and this was one of those. I really felt that they were a band in the making that had the makings of something really good. That started the process. The original concept was to film the process of the band coming from Memphis to Nashville or L.A. or wherever it was going to be, that whole sort of journey. I said, then forget about L.A., I’ll fly to Nashville. There are a great couple of studios there, one that I like called 16 Ton. I said, ‘Why don’t you just have the band come to Nashville, and we will rehearse there and track there?’ I remember working with the band for the first time. They were on this big stage that we had rented. It was pretty magical. It seemed to work right from the get-go.”

While he agreed to produce American Fiction, there was still work to do. I was fortunate to witness Kramer working the band through an arrangement. Tearing up someone’s musical work — even for the better — can be emotionally difficult. Kramer kept things moving, mainly through his sense of humor and an energy level that is rare in a man his age.

“The coolest part to me about something like that is that you don’t see it,” Fusco says. “You don’t hear it. You didn’t think of it. Then when he brings it up, you’re kind of shocked at first. Then you try it, and you’re like, ‘He’s right.'”

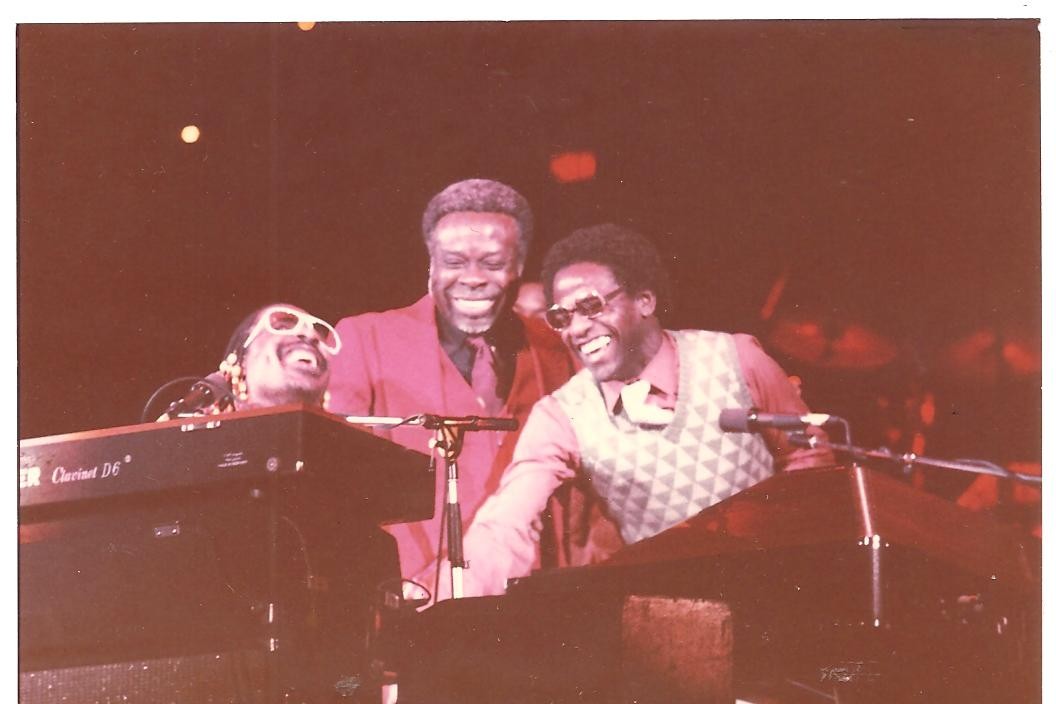

“He also produced this band more than I have ever been produced,” Moore adds. “But he didn’t really change much. The first song on the record is called ‘Mercy on Me.’ We played the song down for him. Blake, our bass player, is playing this line at the end. He flipped out about that and said, ‘I want to center that at the beginning.’ It’s like a feature. It’s really cool: It’s melodic, but it’s really tight. He didn’t rewrite anything. He just changed focus points. His attention to detail on every instrument is so focused. Sometimes, you think a guy gets older and he softens. No. He’s turning up distortions, telling Pat, ‘Make the B-3, dirty it up.’ He’s still very much a rock-and-roll producer.”

“I’m not going to take on a band that doesn’t have their act together, Kramer said. “I’m not going to take on a band that can’t play. That would be impossible. I’ve been there, done that. It’s not very pleasing. They have great musicianship. That’s for sure. It’s only getting better. This time around, they are way tighter than they were before. They’ve learned an awful lot. In the recording process, when we were recording in Nashville and then going to L.A. to do the overdubs, I beat them up pretty severely. Not physically. But it’s a tough process making a record. I think they learned the discipline, or at least the basic disciplines, of how to make a record. The wonderful thing about them that I did notice from the get-go — even from the early stuff a few months back —they were very ready to take new information in, and they were curious about my direction. Fortunately, it all worked out. It is a band decision. But it’s mine in the middle of all of that. I try not to say, ‘You have to do it this way.’ I love to hear all of the various parts from all of the various directions that each individual has. I try to guide it gently along a path. Sometimes, I have to put my foot down. But for the most part, I try not to put a two-by-four over their heads. Although, as I said, I would like to.”

As much as Kramer longs to put a two-by-four over their heads, he remains impressed by these young Memphians.

“Landon is a master of quirkiness,” Kramer said. “Pat, our keyboard player, is phenomenal at keeping parts of the blues going. Chris has a wonderful voice. He has a gift, a fabulous voice. I try to guide him as much as possible in terms of not being too repetitive in a certain range and all that sort of thing. But that’s all the technical thing. The bottom line is he sings his ass off. Great guitar player. And Blake is superb about being understated and playing just the right thing on bass. Our drummer is phenomenal. It’s a great band now. Before, they were just sort of parts that were trying to fit together. Now they are fitting together. It’s really gratifying for me to work with these guys. They have done their homework. When I walked in here, it made it very easy for me to go, ‘OK, there, there, and there; we need to do some editing. We need a better bridge. We need a better thing.’ Within minutes, we are there. That’s fantastic. Some bands you work with, you could be frickin’ hours trying to pull things together.”

Amy Flesicher

Amy Flesicher

Geoffery Brent Shrewsbury

Geoffery Brent Shrewsbury