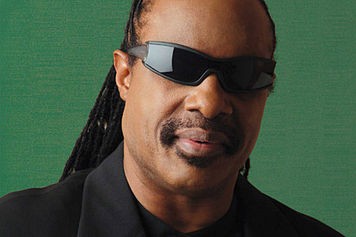

Don Mann passed away last week. The 65-year-old Memphian was known in musical circles as the guiding force behind Young Avenue Sound, the studio he founded with his son Cameron in 2001. Mann was a fundamentally curious person whose talents were found in many disciplines. His appreciation for design and production led him to success in business and to a lifetime of curating excellence, whether it be in antique cars or the best audio equipment ever made. His influence runs deep in the Memphis music scene.

“My father’s love of music, in terms of getting involved with it, began when he was at Brown University,” Cameron says. “Throughout the ’60s and ’70s, he was very much in the counter-culture scene, and he managed a band called Rufus [not the Chaka Khan-associated band]. I think he got that experience of being on the road and managing a band. He learned a lot and enjoyed it. Of course, the music business was very different back then. That band ended up getting a major label record deal. Like a lot of bands, when the record deal came, they imploded and that was that. That experience really informed him. It planted a seed that would blossom many years later.”

Mann was a peripatetic sort early in life. He wanted to write and majored in creative writing at Brown and wandered over to Rhode Island School of Design where he studied furniture design. He married his first wife, Natacha, the daughter of a Russian pianist who had studied with Rubenstien and Horowitz. They spent time in Durham, North Carolina, where Don studied architecture. The couple returned to New York, where he completed an MBA at Columbia. Cameron was born in New York as Don was mastering the nascent business of direct marketing. The Manns returned to Memphis, where Don co-founded Malmo Direct.

“When he was at Malmo, he was part of the account team that was assigned to Chips Moman when Billy Dunavant and Fred Smith and Dick Hackett brought him into the purple firehouse,” Cameron says. “That was going to be the first resurrection of the Memphis music industry.” Cameron is the former director of the Music Resource Center, a subsequent resurrection effort. He chuckles at the irony and continues:

“There were a lot of people behind that in the city of Memphis. Malmo had that account. My dad said there were some interesting philosophical differences between Chips and the team. Apparently it culminated in someone calling a big meeting for a ‘come-to-Jesus moment.’ Billy Dunavant had Chips’ back. He was like, ‘What’s all this fighting going on? Who is the expert on music in the room?’ Everybody pointed to Chips. And he said, ‘We should listen to that man.’ I’m sure there are more details to it than that. He told me that story to exemplify the big personalities that were at play in that situation.”

Mann left Malmo to form Fusion Marketing Group, a company he sold in 1998. While his primary passion was for antique automobiles, Mann frequently invested in music-related ventures including an original investment in B.B. King’s Blues Club and the Cadre Entertainment with Tommy Peters. The Cadre experience set the stage for Young Avenue Sound.

“Tommy Peters put together a record label with Norbert Putnam. They put out records on Dobie Gray, Eddie Floyd, Ruby Wilson, a few of the Stax people. It didn’t last very long.”

Other investors were more interested in the real estate deal involving the building. Mann wanted to continue on the musical path.

“He wanted to keep going,” Cameron says. “He said, ‘We’ve only been doing this for a year and a half.’ So he ended up buying most of the studio gear from the Cadre Entertainment deal. That was the basis for what would ultimately be Young Avenue Sound. By the time I got back to Memphis, he was already looking at real estate and trying to figure out if he was going to buy a place. He asked me if I wanted to be a part of it, and I said, ‘Hell yes.’ If my dad wants to start a studio and a label in Memphis, nothing sounds better than that to me.”

Mann hired British studio architect and designer Alan Stewart, who worked on Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady studio, the Penthouse at Abbey Road, and Eric Clapton’s studio. Willie Pevear was the first engineer at Young Avenue Sound. Pevear came from the Nashville branch of L.A. super-studio Ocean Way having worked on records for Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings.

“Dad loved all of that old gear. For him, it was like cars. Insofar as they don’t make them like they used to,” Cameron says. “He appreciated that even if he didn’t use the gear. He would read about it exhaustively. He didn’t use the gear, but he knew what was cool. He bought the [recording console] from the president of Telefunken USA from California who took it on as project like one would a car restoration. [The Beatles were recorded on Telefunken preamplifiers.] He restored it to perfection. That was the pièce de résistance in Studio A. Everybody wanted that, and, to this day, people love it.”

Mann enabled many Memphis recording engineers whether they were veterans or newcomers. There are many working engineers who learned their trade at Young Avenue Sound or who found work there when their careers took unexpected turns. Nil Jones, Jacob Church, Skip McQuinn, Kevin Cubbins, and Elliott Ives are among those who documented Memphis’ music in the studio that sits a block off of Cooper and Young: Yo Gotti, Skewby, Saliva, Jimi Jamison, FreeSol, Al Kapone, 8Ball & MJG, and Don Trip recorded there. So did Bobby Blue Bland, Bobby Rush, and Elvis Costello.

“Skip ended up being a real mentor to me,” Cameron says of the engineer who died in 2011. “He and my dad were great counterpoints. His music career started in Georgia. He lived close to peanut farms and left home when we as 16 to play drums for a mother-daughter burlesque troupe. He ended up on the road with Willie Nelson, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. He was a longtime associate of Chips Moman and Jim Dicksinson. Skip represented a link to that Memphis music scene, kind of the old school.

“My dad’s whole impetus was that he loved music and I loved music. He never really said this directly to me, but he thought it would be cool if we did something together. It was an unspoken thing. He really had this visionary desire to help Memphis musicians. He wasn’t trying to go to South by Southwest and sign a big artist from Seattle. It was all about what we can do to record the most talented artists we can find.”

Don Mann led a fascinating life and left his mark on the Memphis music scene in his own way. Cameron says:

“As he was an introvert and really did not toot his own horn, I think he did kind of end up in the shadows of Memphis music, which was fine by him.”

Photo by Don Perry

Photo by Don Perry  Joshua N. Timmermans

Joshua N. Timmermans