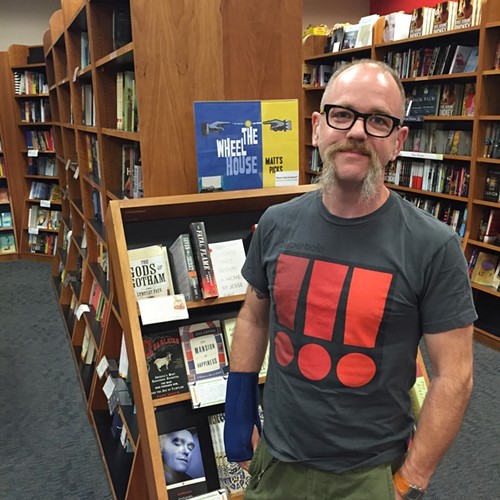

Joshua Hood had already gone through QueryTracker.com, a database of literary agents, and gotten a slew of rejections in answer to his query letters. He’d exhausted WritersMarket.com too in search of an agent. But through the annual conference known as ThrillerFest, an agent got interested in Hood’s manuscript, a contemporary military thriller set in today’s worn-torn Middle East, and she got interested in Hood himself.

He told her about being a decorated war veteran and former member of the 82nd Airborne division in Iraq and Afghanistan, and after reading his manuscript, she had two things to say. The good news was: Hood had a story to tell. The bad news: Hood didn’t know how to write a book. There were rules to storytelling in general and added rules to writing a successful thriller in today’s market, and Hood needed to learn them. She gave him the name of a “story doctor.”

[jump]

The good doctor was expensive, but he was worth it to Hood, a native Memphian who lives today in Collierville and works as a full-time SWAT team member for the Shelby County Sheriff’s Office.

Hood eventually got an agent, who in turn got Hood a two-book deal with Simon & Schuster’s Touchstone imprint. And now, Hood’s debut novel, Clear by Fire, is here, and he’s set to begin an author tour. First stop: The Booksellers at Laurelwood on Wednesday, August 19th, at 6:30 p.m. for a reading, talk, and signing.

Last week, the Flyer talked to Hood too in what was supposed to be a 20-minute phone interview, but it grew to more than an hour. The lengthy Q&A that follows is an edited version, but it gives a good idea of the kind of writer Hood is and the kind of man.

How did you go from the military to member of the Shelby County SWAT team to published author? You knew all along you wanted to be a writer?

Joshua Hood: I always wanted to write. It was a goal. But you grow up telling people that, and, like being an astronaut, they tell you, “Well, that’s good, but you have to get a real job.”

My dad, who’s an artist, and my mother encouraged me to pursue the dream. They kept the creative juices in the house going, though in high school I’d been diagnosed with ADHD. Literature and writing came easy; things on the analytical side were more difficult. So I read a lot, and at the University of Memphis, I majored in English and in 2003 graduated with a degree in technical writing. Then I enlisted in the military and was assigned to the 82nd Airborne.

Which is where you began getting ideas for your debut novel?

The genesis of Clear by Fire was planted when I was in Afghanistan, and it started with a concept: What would happen to someone in the military who has a particular skill set and a way with languages and who could physically blend in with the local population?

While in the military, I was one of the few guys who wasn’t an officer but who had a college degree. People made fun of me, including my squad leader, but when we became closer, I told him I wanted to become a writer. I’d tried to write a few things, but it wasn’t, I guess, the right moment or I wasn’t in the right frame of mind. And being just a regular paratrooper, I didn’t figure my story was very interesting. I resigned myself to the fact that I wasn’t ever going to be a writer. It was a childish dream. I hadn’t written anything seriously at all since college.

Then one day, in August 2013, I got an email from my squad leader, who’d just published a novel. So I thought, if he can do it, I can do it. I told myself, let’s not procrastinate, do something, if you’re failure at it …

One of the things I hold onto besides my faith is that I’d like to be able to say at the end of my life, I don’t have any regrets. Throughout school … I went to a private school on scholarship … remedial classes … hard work … getting to goals slower than everybody else: That was a lesson I learned very early in life. As my grandmother used to say to me, if you’re comparing life to cars, “There are Ferraris, and you happen to be a Volkswagen: dependable. It may not go a hundred miles an hour, but it’s going to get you where you want to go.”

She was an educator in California, and though I was born and raised in Memphis, I spent every other summer on the West Coast, where my father is from. It’s a land of possibilities, almost Horatio Alger-like, it showed me things.

I was equipped with everything I needed when I began to write this book. And I figured it would be an uphill battle, but as long as I never quit, as long as I put a hundred percent of my effort into it, there would be something noble even in failure. I was also raised a Christian. I had a sense of purpose. The Lord would bless what I was writing. What would success look like? What would it mean? I went forward on faith.

How much of “Clear by Fire” is based on your firsthand combat experience? The violence and confusion you describe have an immediate, visceral impact. Those gun battles go with the conflicting moralities you describe and some pretty questionable military methods.

The action scenes were all based on what I’ve witnessed, on being shot at.

In the book, we start out with a massacre in Afghanistan, and that’s been documented, though no one’s ever come out with exactly what happened. But a U.S. special forces troop was thrown out of Afghanistan’s Wardack Province for something that did happen there.

As far as American special forces and morality go: In World War II, the press didn’t have the access to the horrors that they do today. And as I was writing Clear by Fire, I was living a modern-day Heart of Darkness. I thought of my character Colonel Barnes as Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz. I asked myself: What happens to a man who’s been given absolute power in an environment where morality and ethics aren’t placed on him? When Kurtz in Heart of Darkness says, “The horror! The horror!,” is he talking about his life? What he’s done? Or what others have done and he’s seen?

Did you ever serve under someone who resembles Barnes?

The concept of Barnes came from a bunch of people, archetypes. Barnes looks a certain way, acts a certain way. He has a swagger. I never met anyone who committed war crimes, who did things — illegal things — to civilians. But I did meet people like Barnes. For them, it was: mission first, justify the means anyway necessary. That was what success looked like to them. Whatever happened to the people fighting or to civilians, that took a back seat to a mission’s objectives. That’s where Barnes was coming from.

Your lead character, Master Sergeant Mason Kane, who has a very good skill set, goes from hunting terrorists to being hunted himself as a terrorist by some very unsavory U.S. officials: Is there any of you in him?

Writing Mason, I dealt with some of the questions that I had in the military. You’ve invested in something bigger than you are. You have to act a certain way to be accepted, but the whole thing is: You’re representing America. You’re not there to embarrass America. You love your country. You’re trying to make the world a better place, but things happen, and you’re left with an emptiness, confusion. And suddenly, if you start thinking outside the lines, you become an outsider too. That’s what I wanted to capture in Kane.

There are people who stand up for what is good, in society or anyplace else. And there are people who think the only type of justice is Western-style. I grew up watching John Wayne. The good guy was allowed to kill the bad guy, and violence was the immediate answer to a problem.

Your road to publication was another problem.

I was really lucky, blessed. The rejections were coming in, and it got to a point where I felt this book is as good as it can get. I worked overtime at my job to get the money to pay for what needed to be done on my manuscript. My wife was awesome enough to allow me to invest the extra money in a “story doctor.” All we had to do was keep the faith. My wife and I were dedicated to the process.

That process included a lot of legwork on your part trying to get an agent.

I decided maybe it was time to change my query letter. I’d submitted one letter to an agent, he rejected it, and that hit hard. Then I re-used an old query letter, and that same agent accepted me to be his client.

What was so different about those two letters?

Honestly, I don’t know. But his response was: “This looks great. Would you like me to send [your manuscript] out to some editors?”

I didn’t know what that meant. I was like, “I’m not sure. I just want you to represent me.” And he wrote back, “Well, that’s what I’m doing!”

I was ecstatic. This was the first success I’d had, back in August 2014. Then I got an email from that agent: Touchstone wanted to offer me a contract. I texted him back: “That’s hilarious,” thinking it was a joke by the guys at work. My agent wrote back: “That’s the weirdest response I’ve ever had. They’re ready to send a contract for a two-book deal.”

I sat there. Then my wife said, “What’s wrong with you?” I was like, “I just got a publishing contract from one of the big five publishers, and I’m not sure if I’m going to pass out.”

Was there then more “doctoring” to do on the book?

My editor at Touchstone said they wanted to expand the scope, to have a political aspect. He introduced new concepts, and the most ironic thing was: My female character, Renee Hart, who’s in special operations, was there from the beginning, but in my first draft she got killed.

I was told maybe keep her to the end. She can be a role model for women, somebody female readers could look up to in a genre where, in my opinion, women characters often come across as disposable assets, and wouldn’t it be great to have a female character who’s on par with the male characters? Maybe some readers could identify with her — the fact that Renee had a learning disability growing up, but she could still join the military, serve her country, and have a place in this closed alpha-male society. I already get more emails about Renee than any other character in the book.

You still working full-time for the county sheriff’s office?

Yes, I wake up at 5 a.m. to write, and during the day it’s almost a compulsion — thinking about a story idea. And now I’m working on a third book — if I get the opportunity to have a third book published. I’ve got the outline, the same basic characters. But the thing about writing a series is: How do you come up with something that will still be relevant?

Such as the rise of ISIS? It doesn’t appear in “Clear by Fire.”

Well, it does in the second book. It plays a central role.

On your author page at Simon & Schuster, you cite Somerset Maugham’s “The Razor’s Edge” as an important influence. Why is that?

I love that story. The main character goes to this altruistic “place” because of the horrors he’s seen in the war. He brings Eastern thought back to people who are pursuing the brass ring — money, power — to bring them happiness.

But in what we choose to do with our lives, there has to be some reward within yourself. Writing Clear by Fire, it would be easy to say the joy was in the journey. But if you’re not getting to where you want to go, it’s also easy to develop a negative attitude, to blame others.

From The Razor’s Edge I took the fact: You have to define what success is for you, and as long you hold onto that and you’re true to who you are, what you do rewards you. It replenishes you. For me to write a book that’s going to live on even if I don’t progress any further … maybe there’s a kid out there who’s thinking, “I wanna be a writer,” and his parents are saying, “You can’t do that. You have ADHD. Writers don’t make money.” Maybe that kid can look at my book the way I looked at The Razor’s Edge, and he or she can say, “Here’s a guy who was true to what he wanted, he stayed with it, he managed to accomplish something.” You can accomplish your dreams if you’re willing to work.

You’re about to go on a booksigning tour. You ready for it? Ready to maybe become a “name” author?

I’m not a famous person. I don’t want to be a famous person. I’d be perfectly happy to write for the rest of my life as a full-time author. I’d love to be respected as a craftsman. I’d love for readers to say, after finishing a book I’ve written, “I’ve gotten a good return for the money I put in.”

Spoken like a true craftsman.

In The Book of Five Rings, Miyamoto Musashi compares the warrior and the craftsman, and I was raised with the saying “It’s a poor craftsman who blames his tools.” Someone’s always wanting to say, “You’re a writer. You’re an artist.” But I don’t particularly think a writer is an artist. A writer is a craftsman.

During downtime, I like to build furniture. I built the desk I write at. And I’m reminded of the Odyssey. Odysseus built the bed that he slept on. That image of the bed has really stuck with me … And his wife, Penelope, making her tapestry. They’re both creating something that has a place in eternity.

My desk is not a perfect desk, but I created it. It functions as a desk. And I hope my book functions as entertainment … functions maybe as an influence on people too, helps whoever — veterans, aspiring writers — because I learned a lot through this process.

I learned that for something to be good, it’s like making wine. It has to age. It has to go through these little steps. And if your name’s on it, you want it to be the best it can be — not like some author where readers think he “phoned” it in. I don’t want to be that guy, the guy whose name on the cover is bigger than his book’s title. I want my readers to think, “He put in the effort, he didn’t take any shortcuts, and we appreciate that.”

With me, growing up the way I did, my experiences in the military, it’s been ingrained in me to remain humble. I look at my writing like a knuckleball pitcher. There are only a few knuckleballers out there, and when it’s working, it’s beautiful. But the pitcher never knows: Is this pitch going to come off right? Am I going to break a nail and not be able to throw this ball? Is the ball going to end up over the plate?

There is a fear of failing, though — not failing myself but failing all these people who invested their time and energy and belief in me. And one of the reasons I wrote Clear by Fire … besides telling a good story, I wanted a voice out there for veterans like myself — a voice that says you’re not alone in the things you’ve experienced. You’ve done a noble thing for the country. As a soldier, it isn’t up to you to decide the politics, but you’re never removed from morality, from right and wrong. Some decisions — about being deployed someplace, of fighting a war — they’re not your decisions to make, but you made a commitment. I tried to describe one soldier, the costs to that soldier: Mason Kane.

With this book, I see myself as the new guy on the block. I don’t have huge expectations, but I’ve been blessed beyond anything I could have imagined. And my biggest goal for my book?

People who have a good job don’t look at $26 [the cost of Clear by Fire in hardback] as a whole lot of money. But when I was growing up, $26 was the difference between being able to feed [the family] for three days or going out to eat for one meal. For this book and everything I write, I want the reader to be able to say, “I invested my money in this guy, and he didn’t let me down.” •