Memphis poet Tara Mae Mulroy, author of the chapbook Philomela (Dancing Girl Press), teaches middle school Latin at St. George’s Independent School, so it’s no surprise that she’s often inspired by the gods and goddesses of classical mythology: Persephone and Hades, for example, in Mulroy’s poem “A Letter” or Hera and Zeus in “On Our Anniversary.”

Those two poems are from Mulroy’s nearly four dozen poems in her unpublished collection called Swallow Tongue, and she’ll be reading from her work on Friday night at story booth on North Cleveland.

[jump]

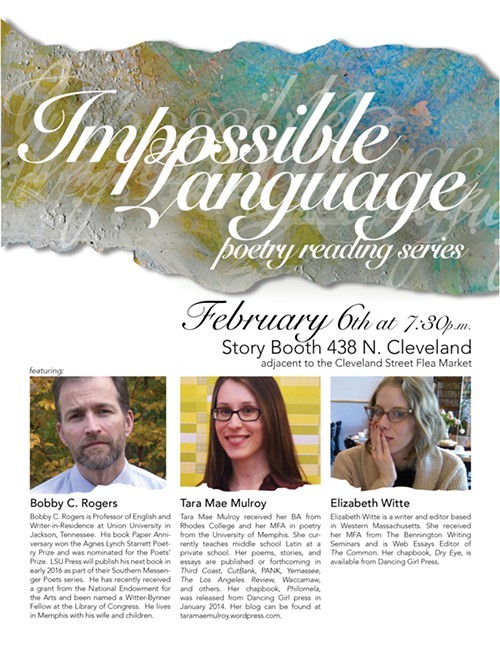

The event, organized by another Memphis poet, Heather Dobbins, is part of the “Impossible Language” poetry reading series, which this Friday night will also welcome two other writers: Memphis poet Bobby C. Rogers, professor of English and writer-in-residence at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee, and Massachusetts poet Elizabeth Witte, author of the chapbook Dry Eye (Dancing Girl Press) and an editor at the literary website The Common.

Swallow Tongue is Mulroy’s first full-length manuscript, and if it often references ancient myth, it also puts the reader between a rock and a hard place: “Scylla” opens the collection; “Charybdis” closes it. At least for now. As Mulroy explained in a recent phone interview, “I love that phrase — “between Scylla and Charybdis” — but I don’t know if readers will know about it or know what it means. I just wanted to play with it. It may not work even for me in a couple months.”

Which is okay, since Mulroy is still shopping the manuscript around to publishers. The collection started as her thesis requirement for an MFA at the University of Memphis (where Mulroy worked with John Bensko, after working with Tina Barr at Rhodes College). She’s sent the manuscript to several presses, but she’s also gone back in, written new poems to add to the manuscript, re-edited older ones, reorganized the sequence, or scrapped some poems entirely, so that, according to the author, “the manuscript as a whole is very new to me.”

Just as the mythological stories that have inspired Mulroy may be new to readers. Doesn’t mean readers won’t be moved by the poems in Swallow Tongue. Those poems can be in the form of traditional verse. They may be prose poems. They can be violent or loving, bloody or tender, sorrowful or celebratory, but all of them are artful, be it the stuff of myth or contemporary life.

“The poems may be loosely based on myths,” Mulroy said, “but I wanted them to still be accessible to readers who don’t know the myths at all.”

Inspiration can come from anyplace, Mulroy added, and that includes a popular song or an episode of Parks & Recreation. “When you’re open to inspiration,” she said, “you end up hearing it everywhere.”

You can also take inspiration from one’s own experience, though Mulroy said her work needn’t be read strictly autobiographically. She does, however, admit to feeling emotionally connected to Greek and Roman mythical figures. “Hera being left by her husband?” Mulroy said. “That feels autobiographical, but on a detailed level: not at all.

“It’s hard for me to write about specific personal things in my own poetry, because I find I can always express what I need to without recounting the tiny details. The story comes out differently [in the poems], but the feelings are always the same.”

As in Mulroy’s poem “Hurricane Andrew,” from Part I of Swallow Tongue, which does borrow from the poet’s own life.

“That poem details a girl’s father having a heart attack and the doctor saying, ‘He died on the table.’

“That really happened. My father had a stress heart attack when I was 9, and the doctor came out and told my mother that he had died on the table, but they were able to bring him back. In ‘Hurricane Andrew,’ I followed the idea all the way through, imagining what it might have been like if my father had died — imagining a moment that seems small in my memory, but [making it] greater, scarier.”

In Part II of Swallow Tongue, the moments can take on an added dramatic edge, and that’s nowhere better illustrated than in the ambiguous lines from “The Swamp Wife”: “ … Love is knowing/another’s breaking point.”

The third section of the collection includes more recent poems, and they often deal with failed pregnancy — again, if not autobiographically then certainly inspired by Mulroy’s own difficulties and frustrations, as in this line from “How to Talk About Your Miscarriages”: “Motherhood a country you weren’t meant to reach.” Or this from “For the Baby I’ll Never Have”: “The Greeks once fixed broken pots with gold./Each repaired seam lovelier than the terra cotta./Damage has a history, they thought, damage/is beautiful.”

Given these serious concerns, Mulroy’s latest writing project is a big change of pace for the poet. The project is a young-adult, sci-fi novel, and for a writer who’s written realistic literary fiction under Stephen Schottenfeld at Rhodes and Cary Holladay at the U of M, the book has so far been, according to Mulroy, fun to write, even if she isn’t sure where the story will lead.

“I’m 80 pages in!” she said. “And there’s something about writing fiction. It has this fantasy attached to it: I’ll just sell this, and I won’t have to do my day job. I thought, let me try it.”

“Try it. See what it’s like”: That’s also what Mulroy said to those who have never been to a poetry reading or never been to “Impossible Language,” a series she heartily supports.

“Ashley Roach Freeman [who created and hosts “Impossible Language”] and Heather Dobbins have done such a great job making poetry more a part of Memphis,” Mulroy said. “Memphis has a quiet poetry scene, but it’s getting louder.” •

“Impossible Language” with readings by Tara Mae Mulroy, Bobby C. Rogers, and Elizabeth Witte is Friday, February 6th, 7:30 p.m. at story booth, 438 N. Cleveland.