“Seven years of writing. Two years in the making. A lifetime in the living.”

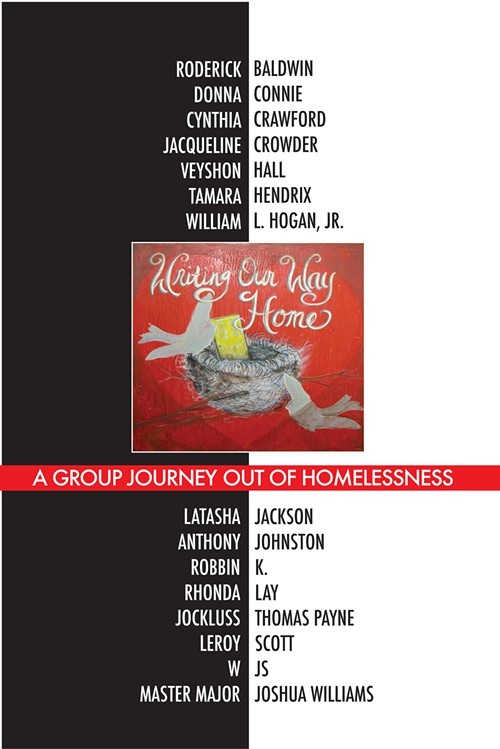

That’s how Writing Our Way Home: A Group Journey Out of Homelessness is described:

For seven years, Door of Hope, the nonprofit organization in Midtown Memphis that serves the homeless with disabilities, has been conducting a weekly writing group;

It’s been two years since local author and Door of Hope volunteer Ellen Morris Prewitt, along with writing-group members, came up with a plan to publish a collection of the group’s writings;

And it’s a lifetime of living recorded in the pages of Writing Our Way Home — writings that describe what life was like before these 15 contributing writers became homeless; what life was like for them on the street; and what life’s been like since they secured housing.

[jump]

Saturday, September 20th, is the date of the book’s official launch at Caritas Village (2509 Harvard Ave.) from 1 to 2 p.m.

In a related event, called “Under One Roof,” there’s a fund-raiser on Saturday at Rhodes College to raise awareness and money for The Bridge. That’s the student-run newspaper launched in the spring of 2013. It features the stories of Memphis’ homeless, who are paid for their contributions and earn money as the paper’s vendors. According to the press release and in the words of Caroline Ponseti, a Rhodes senior and one of the newspaper’s founders: “A year later, we have put $45,000 directly into the hands of the homeless and have given sustainable income to over 250 people with experiences of homelessness, with our top vendors making $380-$540 per month.”

The Rhodes event, which includes remarks from community members, dinner, and an auction of work by artists with experience of homelessness, will take place in the McCallum Ballroom on the Rhodes campus from 5 to 8 p.m.

Expect to see copies of Writing Our Way Home (which includes illustrations by Allison Furr-Lawyer and Jockluss Thomas Payne and photography by Cory Prewitt) at the Bridge fund-raiser. Many of the Bridge contributors have also participated in the Door of Hope writing group. And if those writing sessions have helped to change the lives of the once-homeless, it’s affected the lives of Prewitt, who founded the writing group in 2007, and Andrew Jacuzzi, Door of Hope’s executive director.

“It’s been a wonderful experience,” Prewitt said of the writing sessions, which are held on Wednesday afternoons at the Door of Hope offices on Bellevue. “I don’t think of the topic to write about ahead of time, so it’s a way of jump-starting our thinking. The topic’s announced, and everyone gets quiet. It’s a quiet time for me too. It’s given me practice in writing on the spot.

“When I went into this, I went as a writer and facilitator,” Prewitt added. “So long as people came, we’d meet, write, and, if anyone wanted, share what we’d written. From a program point of view, the group was a way of getting folks back into the community and a way of forming relationships. But it was not only a way for participants to express themselves. It was a way for people to listen.”

The book is a way for Memphians, citywide, to hear from this segment of the population.

“In November 2012, we got ‘intentional’ as far as a book is concerned,” Prewitt said. “The writing group gathered for a retreat at Germantown United Methodist Church to choose the entries we wanted to include and broke the writings down into who ‘we were before we were homeless; my experience being homeless; and who I am now.’”

Now that Prewitt is splitting her time between Memphis and New Orleans, where she has a home, some of her writing-group responsibilities have been taken over by clergy and staff from Germantown United Methodist — church members that Prewitt called not only Door of Hope’s benefactors but also its angels. One of those angels donated the money to publish Writing Our Way Home.

Andrew Jacuzzi, who has participated in the writing group many times, called his work with the homeless the last thing on his mind as a young professional. His mother may have told him that he’d make a good minister or preacher — or, Jacuzzi being Catholic, priest. Or maybe he’d make a good doctor.

But Jacuzzi (yes, that family name gave name to the product his father sold: jacuzzis) said he went about as far as you can get from the priesthood or from medicine: He went into advertising and marketing. A few years ago, though, he’d been laid off, and he was asked by the Door of Hope to act as a consultant on a project. The first writing group he observed really hit home. The topic: Write about a time when you were placed in a situation with an individual you felt like you had nothing in common with and how you found common ground.

Jacuzzi said he left that writing session in tears. He’s been executive director now for almost four years, and he’s seen what Door of Hope’s writing group has meant to members.

“Once you’re on the street, you’ve basically lost your identity,” Jacuzzi said. “People don’t want to see the homeless, so they avoid the homeless. Participating in the group has given them a voice, a place to tell their stories, express their thoughts. One gentleman said he’d been identified for most of his life as a substance abuser and criminal. His number in prison was his identity. Now he’s identified not only as a member of the writing group but as a published author. It’s changed his whole perception. It’s reconnected him with society.”

When Writing Our Way Home was on sale at the recent Cooper-Young Festival, contributors were connected to a larger society and even asked to sign copies of the book. “Their faces were beaming,” Jacuzzi said. “The book has given these authors a whole new sense of pride and belonging.”

The book, Jacuzzi added, will change readers’ attitudes too.

“I tell people that nobody grows up wanting to be homeless. And this book will change your perception of what homelessness is and who can be affected.

“We deal at Door of Hope with the chronically homeless (meaning, individuals who have been unsheltered for a year or longer), and they’re disabled, physically or mentally. It’s the most difficult segment of the homeless population to deal with. Our job is to get them housed, safe, with benefits and increased self-determination. The goal is for them to become healthy and productive members of society.”

Door of Hope, according to Jacuzzi, now has dozens of individuals in housing, but it helps hundreds more a year, with, on average, 4,500 meals served annually. But even Jacuzzi admitted he wasn’t sure, at first, that working with the homeless was exactly his “cup of tea.” He’d been in marketing. He’d never worked for a nonprofit. But he’s now fallen in love with the people he works with. He’s fallen in love with the services Door of Hope provides.

“And maybe my mom was right,” Jacuzzi added. “Here I am, after a career in advertising … ministering, providing care.”

The book launch for Writing Our Way Home is free and open to the public. Go to the Door of Hope website for further information and follow Door of Hope on Facebook. The book is also available at Amazon. Proceeds from the sale of the book are split evenly among the 15 contributors and Door of Hope. Contributors who sell individual copies keep that share of the profit for themselves.

Tickets to the “Under One Roof” fall fund-raiser at Rhodes can be purchased for $50 here. For more information, contact Caroline Ponseti at caroline@thememphisbridge.com. •