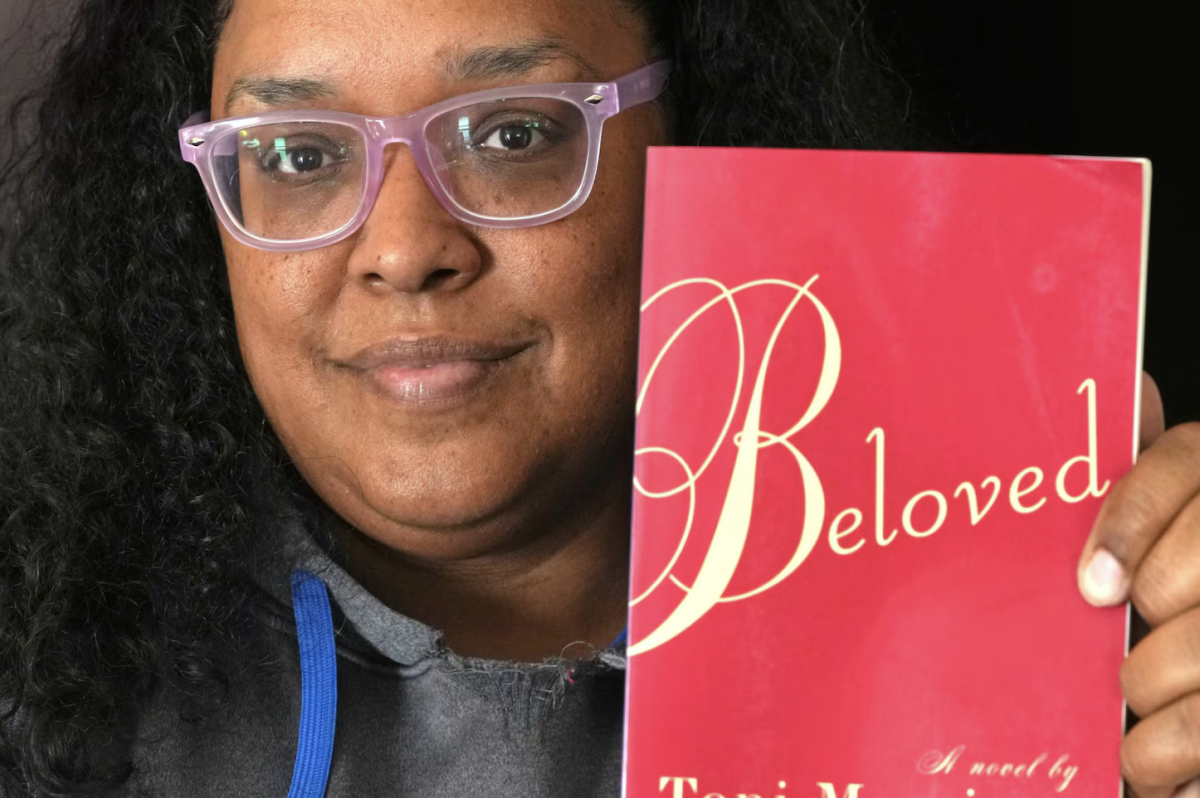

Jennifer Edwards was a teenager in Arizona when she first read “Beloved,” Toni Morrison’s haunting novel about sexual violence and the brutal realities of American slavery.

“It had a profound effect on me,” she said, citing the empathy, historical understanding, and critical thinking skills the book imparted.

Now a mother of two sons and living in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Edwards wants teens in her community to have access to her all-time favorite book.

But under a recently revised state law broadening the definition of what school library materials are prohibited, her local board of education is set to vote Thursday on whether to pull the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel and six other books with mature themes from the shelves of Rutherford County Schools.

“Banning books is not OK,” Edwards told the board last month as it began reviewing the materials. “Just because you don’t like what the mirror shows you doesn’t mean you put the mirror down.”

This week’s vote comes after the district, south of Nashville, already removed 29 books from its libraries this year under a previous policy, part of a wave of purges on campuses across Tennessee and other states.

In Tennessee, that wave started under Gov. Bill Lee’s 2022 school library law requiring periodic reviews of catalogs to ensure materials are appropriate for the ages and maturity levels of the students who can access them. Librarians and teachers had to publish their inventories of book collections online for parents to view. Early removals included books about marginalized groups, including people who identify as LGBTQ+, and descriptions of slavery and racial discrimination throughout U.S. history.

This spring, scrutiny escalated. Republican lawmakers added a definition of what’s “suitable” and, based on the state’s obscenity law, prohibited any material that “in whole or in part contains descriptions or depictions of sexual excitement, sexual conduct, excess violence, or sadomasochistic abuse.”

In the absence of state guidance on how to interpret the changes — What constitutes excess violence, for instance? Are photographs of nude statues allowed? What about Shakespeare’s “Romeo & Juliet”? — some school boards like Rutherford County’s are putting questionable material to a vote. Educators in many other districts are quietly culling their shelves of certain books.

A recent survey of members of the Tennessee Association of School Librarians found that more than 1,100 titles have been removed under the changes, with more under review. One librarian anonymously reported pulling 300 titles at a single school since the start of the academic year. Only a sixth of the organization’s members responded to the survey.

“We may never truly know the level to which books have been removed from school libraries in Tennessee,” the organization said in a statement, noting that large-scale removals may cause some libraries to fall under the state’s minimum standards for collection counts.

“A literal interpretation of this law may have the unintended consequences of gutting resources that support curriculum standards for fine arts, biology, health, history, and world religions, to name a few, especially in high schools, where AP curriculum and dual enrollment courses require more critical texts,” the group said.

Lindsey Kimery, one of the organization’s leaders, said the law’s rollout has created “chaos and confusion” for school librarians.

“Some librarians have received guidance from their central office; some have not,” she said. “Some boards are updating their policies for handling book challenges to align with the law’s changes. Some districts have interpreted the law to mean they should preemptively go through their collections and pull anything they think has one of the prohibited topics in it.

“It’s all over the map,” Kimery added.

‘Phantom book banning’: Censorship in the shadows

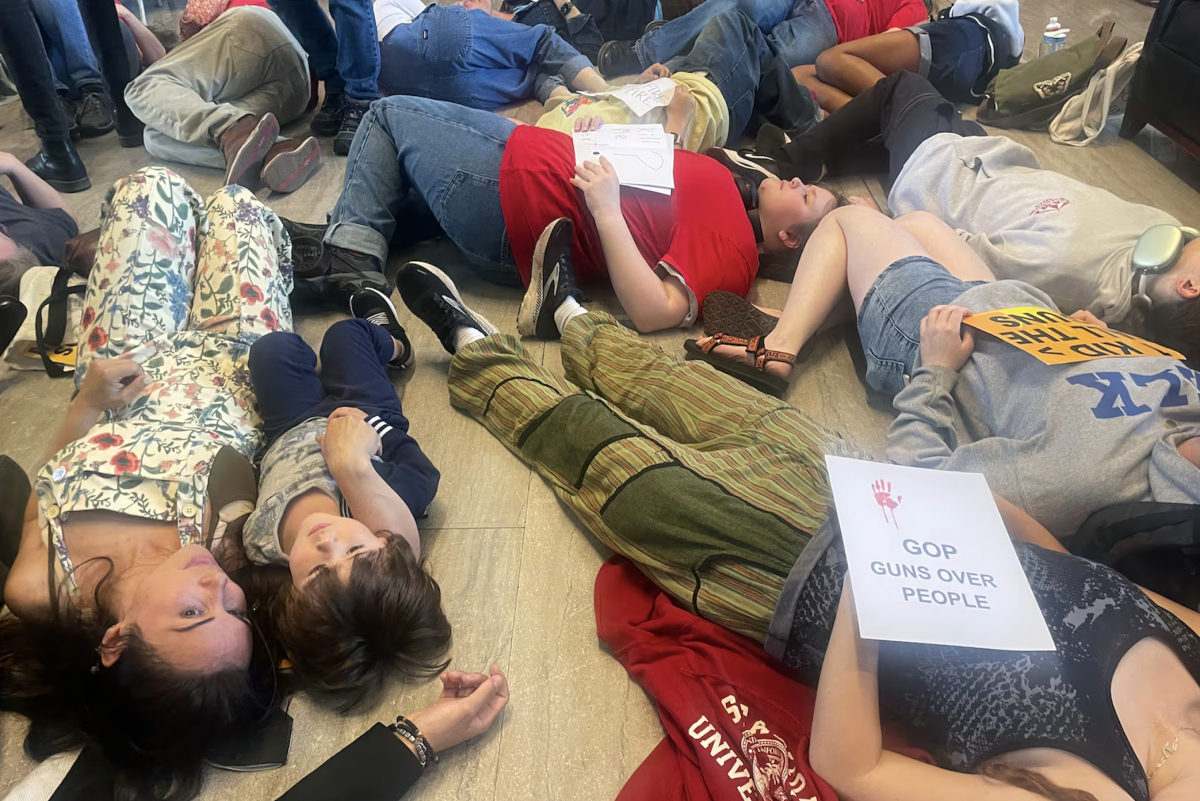

The quiet censorship is being noticed by First Amendment advocates, from the ACLU of Tennessee to Julia Garnett, who graduated last spring from Hendersonville High School in Sumner County, north of Nashville.

Garnett started a free speech club at her high school during her senior year. Now a freshman at Smith College in Massachusetts, she is the youth spokesperson for the American Library Association’s Banned Books Week, Sept. 22-28.

Last week, she searched her alma mater’s online library catalog to look for books by Sarah J. Maas and Ellen Hopkins, whose popular young adult novels are frequently challenged or banned due to their mature themes and sexual content.

None were listed.

“They used to be there, but they’ve disappeared,” said Garnett. “I call it phantom book banning, where libraries are being censored, but not in a public way. I think that’s what scares me the most.”

The law is vulnerable to a federal challenge on First Amendment grounds, said Kathy Sinback, executive director of the ACLU of Tennessee. The statute’s vagueness, a lack of compliance guidance from the state, and the uneven way the law is being applied across Tennessee are among issues that open the door to a lawsuit.

“But we’d love to see the legislature fix the problems next year without having to pursue litigation,” Sinback said. “We’d like to see it made constitutional in a way that will ensure our children have access to the literature they deserve.”

Legal precedents support students’ First Amendment rights

The House sponsor of the law’s recent revisions, Rep. Susan Lynn of Mt. Juliet, did not respond to emails asking if she’d be open to revisiting the law. Some of her critics worry the goal is ultimately to take a legal challenge to the U.S. Supreme Court, where conservatives hold a majority.

The Senate sponsor, Joey Hensley of Hohenwald, said he believes the law is constitutional.

“I’m always open to making laws better,” he said, “but I don’t think this interferes with people’s First Amendment rights, and I’m personally not hearing about problems with it. The law’s intent is simply to ensure public schools do not give children access to materials that are not appropriate for their ages.”

Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, said higher courts have consistently sided with First Amendment advocates on challenges to content in school libraries, even as efforts to ban books in public schools and libraries reached an all-time high in 2023.

The school library is supposed to be a place of voluntary inquiry — a safe space for students to explore ideas under the supervision of adults instead of alone on their cellphones.

“This gets to the core of the First Amendment,” she said, “the idea that libraries are a marketplace of ideas, and elected officials should not be able to dictate their contents.”

But it’s also possible that another school library case could someday reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Two book ban cases from Iowa and Texas are already making their way through the federal courts.

Current legal precedent stems from the high court’s 1982 ruling involving a school board in New York state that wanted certain books removed from its middle and high school libraries. In a 5-4 decision, the court ruled against the board and held that “the right to receive ideas is a necessary predicate to the recipient’s meaningful exercise of his own rights of speech, press, and political freedom.”

Justice William Brennan wrote that while “local school boards have a substantial legitimate role to play in the determination of school library content,” the First Amendment doesn’t give government officials the power to ditch books because they don’t like them or disagree with their viewpoints.

Ken Paulson, director of the Tennessee-based Free Speech Center and a former editor-in-chief of USA Today, also cites the importance of a 1969 Supreme Court ruling establishing that students have constitutional rights, too.

The case involved students in Des Moines, Iowa, who wore black armbands to their public school in silent protest of the Vietnam War. The court sided with the students.

“Because someone is 12 or 14, we sometimes think they don’t have constitutional rights,” Paulson said. “But they do, and they’re surprisingly robust. Students are not just students; they are citizens.”

Middle Tennessee district is a book ban hotspot

In Murfreesboro, a college town that is home to about 50,000 students in Tennessee’s largest suburban K-12 district, most titles removed so far were in high school libraries. They generally were contemporary young adult novels containing sexual content and other mature themes, from child abuse and suicide to substance abuse and LGBTQ+ issues.

The books were flagged as “sexually explicit” material by school board member Caleb Tidwell and removed this spring without going through the district’s library review committee that includes a principal, teachers, librarians, and a parent.

Xan Lasko, who recently retired as a high school librarian in Rutherford County, said the directives she received from Superintendent James Sullivan bypassed the district’s usual review process for handling complaints. Instead, Tidwell cited a provision of board policy requiring the immediate removal of sexually explicit material. Sullivan concurred, according to their email exchange obtained from the district through a public records request from Nashville TV station WSMV.

Tidwell, a Republican who was reelected to the school board in August, said he made the requests on behalf of individuals who have expressed concerns but who feared retaliation from the media and individuals in the district.

In his opinion, all of the materials in question violate both the state’s obscenity law and local board policy. Most, he said, have “education value near zero, or very low.” For those that provide historical context, other books that go into those topics — but without sexually explicit language — are available.

“It’s a very contentious topic,” said Tidwell, who has three school-age children. “But if we focus on the content, most of this stuff is pretty clear. Yes, there is some subjectiveness to it, but there’s also a line. We need to determine what the line is, and then hold it.”

Lasko, the former librarian, said that’s what librarians and educators do.

“My biggest issue is that a small number of people were making the judgment to curtail what students are able to read using a vague law,” said Lasko, who now chairs the intellectual freedom committee of the Tennessee Association of School Librarians.

“We have master’s degrees in library science. We know what we’re doing,” she said. “But a lot of times, we weren’t being consulted.”

New library policy diminishes the role of librarians

In advance of this week’s vote on Tidwell’s latest request to remove more books, the board revamped its library materials policy to add language from the revised state law. It also eliminated the 11-member review committee appointed annually by the board to consider book complaints.

Instead, materials that district leaders deem to be in violation of the state’s obscenity law are to be immediately removed from all school libraries and then reviewed for a final decision by the board.

A second avenue for removal — through complaints filed by a student, parent, or school employee — also requires a board vote after receiving recommendations from the principal and superintendent and a review by an ad hoc committee.

“Before,” said the ACLU’s Sinback, “there was a thorough process where every person on the review committee had expertise and would read the book. They’d look at the questionable content but also the overall quality of the material and how it could impact kids exposed to it in both a positive and negative way.”

Now, she said, the decision rests completely with board members.

The changes concern school librarians like Brian Seadorf, who oversees the collection at Blackman High School in Murfreesboro. He asked board members and parents to “just talk to us” if they have concerns about certain books.

“We are educators, we are parents, we are grandparents. … We are good people,” Seadorf told the board on Aug. 22.

Angela Frederick, a Rutherford County resident and school librarian in a neighboring district, added: “The titles you’re considering removing are for older students approaching adulthood. It is developmentally appropriate for teenagers to mentally wrestle with difficult topics. It is also excellent preparation for higher education. Shielding them from books like these does not prepare them for anything but ignorance.”

For Edwards, the Rutherford County parent who also spoke to the board, she’s most upset that “Beloved” is on the chopping block, even though she knows it’s a deeply sad and painful book to read. (Morrison, who died in 2019, said she was inspired to write the novel based on the true story of an enslaved woman, Margaret Garner, who killed her own daughter in 1856 to spare her from slavery.)

“I remember it took me several weeks to finish ‘Beloved’ when I was 15, because I had to put it down every few days,” recalls Edwards, now 42. “I had to have time to process what I was reading.”

“But to restrict literary genius,” she continued, “it just doesn’t make sense to me.”

Marta Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.