Donald Trump’s flight to the border — six days after the Capitol insurrection — focused the nation on the foundational lie (and enduring failure) of his administration: the border wall. While extolling the virtues of the mostly imaginary wall in south Texas, an actual wall, or fence, was under emergency construction in Washington, D.C., to protect the nation’s capital from the president and his insurrectionists.

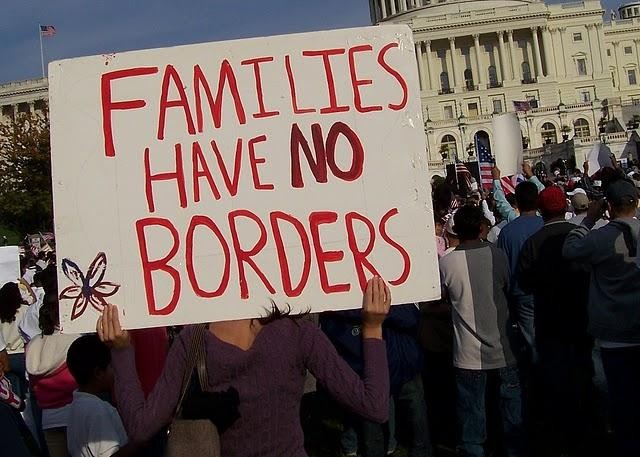

Some segments of Trump’s “big, beautiful wall” went up during his administration — maybe as much as 450 miles. He had promised to build 2,000 miles of wall and told us that Mexico would pay for it. He convinced many in his party that immigrants from the global south were terrorists, yet we found out, sadly, that the terrorists are from right here in the USA. He challenged his party to re-script the entire history of the United States: Trump’s USA was a dark, dystopian place where immigrants were dangerous criminals. Protecting America meant denouncing immigrants and separating ourselves from them both physically and psychologically.

Mati Parts | Dreamstime.com

Mati Parts | Dreamstime.com

Trump’s unfinished border wall was built on a lie, and stands as a monument to a cruel and divisive moment in U.S. history.

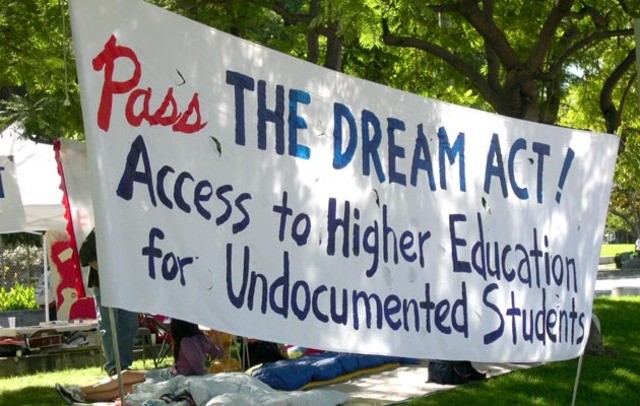

Trump, during his four-year rule, wrecked the asylum laws — laws and norms through which people with a “well-founded fear of persecution” in their home nations could seek asylum in the USA. But Trump forced an agreement with Mexico whereby, essentially, Central American asylum seekers to the USA now must “wait” in Mexico before being offered a hearing with a U.S. judge. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, all such court appearances have been canceled — stranding thousands of Central Americans in Mexico. That country, reeling from political and social violence, economic decline, and COVID-19, is not necessarily a hospitable place for Central American asylum seekers. There was a time when the USA was universally admired for its asylum laws and policies: Our current “Wait in Mexico Indefinitely” asylum policy is hardly helping our sinking standing on the world stage.

We educators, after virtually every crisis, call for “more” education. Looking at and listening to that angry mob on January 6th made me wonder what we’ve done wrong in the education community. Something we must do, immediately? Stop teaching patriotism and start teaching truth. My students — good kids at Rhodes College here in Midtown — are generally amazed to learn about the role of the USA in toppling legitimate governments in Latin America: The list is long, and U.S. actions in Brazil and Chile helped usher in cruel, violent military dictatorships in those places, in 1964 and 1973 respectfully.

Many newscasters on January 6th, so astounded at what was occurring in real time, went to the “banana republic” comparison. They didn’t name specific nations, but they were probably thinking about Guatemala. Guatemala is Guatemala because we helped make it that way. We pushed forward the overthrow of a legitimate, democratically elected government there in 1954, and the nation has never quite been the same. Our political and military leadership was involved, including President Dwight Eisenhower. So too were religious figures such as Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York. Cuba, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, and Honduras (some of the other “B” Republics) have all suffered under the influence of the USA.

Teaching “American exceptionalism” is another part of the problem: Like every powerful nation or society of the past, other more powerful nations will eclipse us, and we ought to have a clear, sound, historically truthful understanding of how (and why) this happens. It happens for many reasons, but a unifying characteristic of every great society’s stall involves leadership that becomes disconnected from reality. Think of France in the late 18th century or Russia in the early 20th century. Think of Trump now.

I suspect we’ll survive the current crisis, wholly manufactured in the USA. Politicians should tell the truth all the time, but they don’t. Educators must tell the truth always because what happened on January 6th suggests an existential failure, and we’ve all rushed in to blame the … Capitol Police. And of course President Trump. But we’re all to blame. The horror show of the Capitol riot represents a failure of our education system, a failure to understand who we are as a society, and a basic failure of imagination. And a failure to speak clear truth to power. It all started with an absurd lie about a wall that never got built — a wall that now surrounds our capital city and just might encroach and suffocate our nation, unless we help take it down. With the truth.

Michael J. LaRosa is a professor at Rhodes College.