The last old-school record company in Memphis plugs away in a lair below Hollywood Street near Sam Cooper Boulevard, unbeknownst to most of the city. Ecko Records was launched in 1995 to release a salty song by a once-popular local artist when no established label would take the chance. Ollie Nightingale’s “I’ll Drink Your Bath Water, Baby” sold enough to make founder John Ward think he could make a living in an unforgiving business and set the artistic tone for the upstart company.

Thirteen years later, the company represents the last gasp of Southern soul in Memphis. Ecko’s artistic roots intertwine with the genre’s most celebrated record labels, and its business practices echo this bygone era.

Ecko functions as part of the chitlin circuit, a conglomerate of African-American nightclubs, concert promoters, radio stations, and mom-and-pop record shops concentrated in the Deep South and sprinkled throughout Northeastern and Midwestern cities. Circuit music, interchangeably called blues, Southern soul, soul blues, and even grown folks’ music, appeals mostly to black listeners over age 35, a loyal good-time group that packs festivals and juke joints to hear the artists who’ve been circulating for decades.

The most popular circuit attractions, including Marvin Sease, Mel Waiters, Bobby Rush, Shirley Brown, and Denise LaSalle, are black singers, also well over 35. Their subject matter, best exemplified in song titles such as LaSalle’s “Pay Before You Pump,” Sease’s “Candy Licker,” and Waiters’ “Hole in the Wall,” reflect the humor, taboos, and lives of grown folks, pretty well disqualifying the music from crossing over to a wider (and whiter) audience.

Though the chitlin circuit operates outside the mainstream music business, Ecko is not immune to the convulsive changes gripping the industry at large. Death has claimed several Ecko artists — first Nightingale in 1997, then Quinn Golden in 2003, and Bill Coday earlier this year — while CD piracy slices Ecko’s sales and corporations gobble up the small local radio stations through which the lifeblood of Southern soul flowed. Ecko survives thanks to its time-honored approach to making music in Memphis.

“It’s tradition-based music, blues, played in a contemporary way,” Ward explains. “A song like ‘Green Onions’ … it sounds contemporary, just as good today as it did whenever they put it out. You don’t just hear it and say, ‘1962, I remember them days.’ As opposed to Motown music, which is pop-based and sounds like oldies now. Stax stuck pretty close to the roots. I feel like what we do is that type of music … same influences in blues.”

Still, Ward insists, Ecko is no reverberation of the classic Memphis sound. “We’re not trying to recreate what anybody did at Stax. It ain’t got anything to do with that — it’s totally contemporary. I can play you a song that we did 10 years ago, and you can’t tell me that we didn’t just do it yesterday.”

A Place of Second Chances

There’s something poetic about Ecko’s studio. For starters, the company makes music for an underground music scene from a subterranean location. Ecko and its fans are invisible to mainstream music, if not the rest of the world. But it’s also a place of second chances. Jim Stewart, who co-founded Stax Records, established an independent record-producing facility there after the demise of his beloved record label left him heartbroken and much lighter in the pocket.

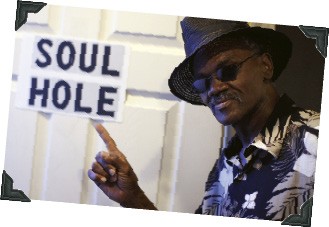

The facility houses offices for Ward and promotion man Larry Chambers and includes the “big studio” — a dark, spacious room decorated with a drum kit, microphones, guitars, and a full mixing board — a smaller demo studio known as the “Soul Hole,” and the Ecko warehouse.

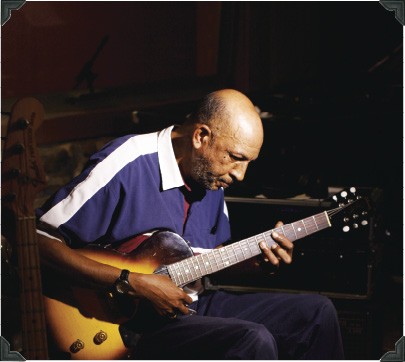

The Ecko staff has three full-time employees: Ward, Chambers, and recording engineer Till Palmer. Old Memphis souls, songwriter Raymond Moore and singer Morris J. Williams, round out the Ecko creative team, both working freelance in collaboration with Ward, who produces and writes the lion’s share of Ecko songs, acts as artist-and-repertoire man, finding the right songs for each artist and laying down the occasional guitar solo.

Ecko records a combination of established circuit performers like David Brinston, former Bar-Kays singer Carl Sims, Denise LaSalle, and Lee “Shot” Williams and up-and-coming talents O.B. Buchana, Ms. Jody, Sheba Potts-Wright, and Sweet Angel.

Ward explains that the singers don’t get rich from their releases, but the recordings and Ecko’s promotion lead to other opportunities. “The artists are out there doing shows; that’s their living,” he says. “A good record gets them more shows and better shows. They’re more in demand. If you have no record, you’re in no demand. The record gets them work.”

“Bookings and record promotion work hand-in-hand,” adds Chambers. “I tell the artists where they’re getting the most play and how to get in touch with the promoter there. The promoter is interested in who’s selling because that’s who’s going to put asses in seats. And that is the bottom line.”

Though Ecko abides by the Stax philosophy, the Ecko sound owes more to Jackson, Mississippi-based Malaco Records, the industry leader in grown folks’ music for the past 35years.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Larry Chambers, promotion man from Ecko Records

Malaco’s formula for success in the contemporary blues market has involved artists who are over the hill by pop-music standards but still appeal to middle-aged Southern black fans. Z.Z. Hill, Johnnie Taylor, Bobby “Blue” Bland, and Tyrone Davis recorded for major labels until disco killed the mainstream popularity of blues-based music. Malaco scaled their operations to turn profits on a 25,000-seller, then made a fortune with Hill’s 1982 hit “Downhome Blues,” which sold in the range of 400,000 copies initially and has since accrued gold-record status as a million-seller.

“‘Downhome Blues’ sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday,” Ward says.

Though blues in name, no listener would mistake an Ecko record for a Muddy Waters tune. Ecko uses mostly programmed tracks mixing a drum-machine beat, synthesized piano and horns, and a single background vocalist dubbed to three-part harmony. The production style reflects the lean economy Ecko operates in, and Ward says that the audience doesn’t mind, though deal-with-the-devil blues purists scoff at Ecko’s sound.

“People don’t go to the store and buy a record for the guitar player,” Ward says. “The majority of music buyers don’t know the difference between an A and an F. They buy what they like. They’re scarcely aware of how good the drummer is or whether there’s a drum machine or a drummer playing at all.”

Workingman’s Blues

Raymond Moore, a soft-spoken 68-year-old grandfather, appears an unlikely source of song titles like “Bone Me Like You Own Me” and “If I Can’t Cut the Mustard (I Can Still Lick Around the Jar).” Moore grew up in Memphis and attended Booker T. Washington High School, where he met David Porter. Porter, who would become among the most prolific and decorated songwriters in the city’s history, liked Moore’s poetry and encouraged Moore to pitch ideas to Stax Records artists. “The very first song I made money on was Carla Thomas’ ‘How Do You Quit (Someone You Love),'” Moore says. “My first check [in 1965] was for between $800 and $900, which was good back then.”

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

Team player: Ecko’s Morris J. Williams

Moore authored tunes for Rufus and Carla Thomas and Sam & Dave before accepting a contract to write exclusively for Fame studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where Atlantic Records sent its top rhythm and blues singers to record.

The Fame contract guaranteed nothing, but it did give Moore and the writing staff access to the talented artists who frequented the studio in the late ’60s and early ’70s, including Clarence Carter, Aretha Franklin, Bobbie Gentry, Wilson Pickett, and Candi Staton. With the exception of Franklin, all recorded Moore’s material.

He left Fame for Muscle Shoals Sound, another studio for hire, hot in the heyday of soul.

Moore worked a regular job in Memphis throughout his songwriting career while enjoying moments of musical success. Candi Staton recorded “I’d Rather Be an Old Man’s Sweetheart (Than a Young Man’s Fool),” co-written by Moore, Clarence Carter (of “Strokin'” fame), and George Jackson (who wrote “Old Time Rock-and-Roll,” among many others). Intended for Aretha Franklin, the song received a Grammy nomination in 1969. The company newsletter at General Electric, Moore’s employer at the time, noted the achievement.

The workplace proved to be a fruitful environment for an artist writing workingman’s songs. “Some of the fellas would joke about something, and I’d use it,” Moore says.

He eavesdropped on break-room chatter and the boasts and laments of everyday life from the very consumers he tried to appeal to in music. “They’d say, ‘Watch it — he’s gonna take it and write a song about it.’ If it’s a good saying, I would,” he says. “This guy was talking about his outside woman, saying all he was getting was the bills and no merchandise, which I thought was pretty nice.”

Atlantic Records thought Clarence Carter’s “Getting the Bills (but No Merchandise)” nice enough to issue as a single in 1970.

Country singer Razzy Bailey cracked the Top 10 of the country charts with a rhythm-and-blues song Moore wrote, “Scratch My Back (and Whisper in My Ear).”

Since his 1996 retirement from the Kellogg’s factory, Moore has drawn inspiration from daytime TV talk shows. “Especially Divorce Court,” Moore says. “The way people act and clown. The way people act on Jerry Springer gives me ideas, too.”

Moore estimates his annual Ecko earnings between $5,000 and $10,000. EMI Records owns his Muscle Shoals work and pays off twice a year, while Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI), the composer and performer royalty clearinghouse, pays quarterly on everything else.

Moore and Ward meet to write every week, and the duo compose at least half of Ecko’s recorded output. “Lately, I almost forget them as fast as I write them,” Moore says.

Sitting in the “Soul Hole,” where he and Ward compose songs in the Ecko compound, Moore explains that he writes as other retirees fish and golf. “This is about the only place I go,” says the lyricist. “Here and church.”

Mr. Promo Man

No one knows the new challenges facing the old-school record company better than Chambers, 61, who’s been with Ecko since its inception, following a songwriting career with Fame and Muscle Shoals Sound, often in partnership with Moore, and at Malaco Records in the early ’80s.

“After John cut ‘I’ll Drink Your Bath Water,’ he called me and said he needed me to work with him. He knew I had done promotions back in the ’80s,” Chambers explains. “There wasn’t any money. It wasn’t even worthwhile talking about a salary. Our deal was done on friendship and survival.”

Chambers has faced challenges that never confronted record promoters in the classic era of Southern soul. “Everyone was doing well until 1999, when the CD burner came in,” he says.

Already operating on a thin margin, bootlegging hit the contemporary blues business harder than most segments of the music industry. Ecko survived thanks in part to Chambers’ boundless energy and old-fashioned record promotion. He carries on in a fast-paced, gravelly voice. “I was working 14- to 16-hour days to get off the ground,” Chambers says. “I’ve slacked up a little bit. Now I just work 10 to 12 hour days.”

Ecko must steadily release new records to keep cash flowing. It keeps Chambers pressing the flesh at every soul blues festival within 150 miles, on the phone day and night, and burning up the highway to meet program directors, disc jockeys, and mom-and-pop shop owners. As the only Ecko marketing employee, his territory is the entire U.S., though he focuses on the Deep South, where the highest concentration of Ecko listeners and affiliated businesses are located.

“I’m working nine records at present,” he says. “I have to make sure all of our music is being played on the radio and make sure the club jocks are working it out in the streets and in the clubs. I’m working stores, too. It all ties in — if a record’s getting airplay in a certain market, you want to make sure that the stores are ready to do something with it.”

Chambers witnessed the decimation of independent black radio in the South up close. He estimates that two-thirds of the family-owned, black-format stations he conducted business with 10 years ago have since been sold to one of the media conglomerates that emerged from deregulation of the radio industry in 1996.

“Back then, we had deejays who could ‘break’ records. That’s not possible now. The deejays don’t have the power. Their time slots are already set up with what they’re going to play,” Chambers says. “Back then, a jock could play your record as many times as he wanted. He could back it up: ‘That was so nice, I’m gonna have to do it twice,’ they’d say. Now everything’s loaded into a computer to come on at a certain time.

“Now you’ve got to be prepared to deal with consultants,” he adds. “One of my consultants works in Dayton, Ohio, and he controls two of my stations in Louisiana, three in Mississippi, and one in Alabama. I have a problem with that because he doesn’t know what people down there want to hear. He takes the power from the program director and deejays in that city who know the audience.”

Still, Chambers says his approach is about the same:

“The pitch is that I’m going to bring an artist into a club to do a promotion for the station. You pitch them the artist that you want to ‘break,’ who isn’t getting exposure. In other words, if he’s already playing the hell out of Barbara Carr, I’m satisfied. If he’s lacking on O.B. Buchana, that’s who I’m going to pitch. The director will be glad to have that free advertising, and we get exposure.”

Exposure is at a premium. Powerful program directors and personality deejays aren’t the only casualties of the corporate takeover of small radio.

“Payola still works with some of the deejays, but they can’t ‘break’ any records,” Chambers says. “They still come to you as if they can, but how are they going to break a record if they’re only on four hours once a week? Or if you only have a 12-hour soul blues program each week? It’s just not possible.”

Resilient Soul

Through all that, Ecko has endured. With the attrition of its talent, the assault on its bread-and-butter radio stations, and bootlegged CDs, the company has hung in there long enough to find a promising new outlet for its traditional soul. “At this point, digital sales are about 20 percent of what we sell,” Ward says.

In fact, downloads represent a return to the singles market that Memphis companies competed in during the soulful ’60s and ’70s.

“It’s a single song that people buy now,” Ward says. “Just like back in the old days.”

Visit eckorecords.com to hear the Ecko sound.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks