The automated garbage truck suits a person like Vera Washington: self-sufficient and economic of motion. She often leaves the Bellevue solid-waste installation on North Watkins before the 7 a.m. shift start time, since she doesn’t need to wait on a crew. She takes advantage of the incentive program that allows solid-waste crews to go home as soon as their zones are clean. She forsakes designated break periods, eats nothing, and takes barely a sip of water on her route. A few Kool super-longs curb her appetite. The 54-year-old grandmother has worked 31 years for the city. Along the way, she has earned the respect of her colleagues, including acting supervisor at the Bellevue installation, Al Sherrill.

“Vera can operate that truck like a man. She’s one of the best I’ve seen,” says Sherrill.

Mike Camurati, west-sector administrator of the city of Memphis solid-waste management department, echoes this praise, without the chauvinism. “Vera’s the best driver we have on those [automated] trucks,” Camurati says.

Though many of us take Vera and her colleagues for granted, their work not only saves Memphis from its own waste, it represents taxpayer dollars at work for the environment. The business is both dirty and costly. Shelby County generated 2.5 million tons of solid waste in 2005 and budgeted $49 million for its removal. But how well does the system work? What happens to all that trash you toss into your green cart and wheel to the street? And what about this copy of the Flyer that you (we hope) toss into the recycle bin when you’re finished with it — along with your glass and plastic items? Just where does all this junk go and what happens to it?

Come along for a journey into the dirty side of Memphis.

Washington and her sister applied for city jobs in 1975. Washington became a crew member on a garbage truck, while her sister joined a dead-animal removal crew.

“My first two-week check was $99,” Washington recalls. “That was a lot of money then.”

Washington eventually earned her class B commercial driver’s license, became a garbage-truck driver, then a crew chief, and then took over an automated truck about three years ago.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Dirty work: the BFI landfill near Millington

Washington is one of the lucky few. According to Jerry Collins, director of public works for the city of Memphis, the solid-waste department employed approximately 1,600 people the year Washington was hired, and while the city has grown significantly since then, the department’s budget only allocates 653 employees today. Automation technology has made workers expendable and sanitation work more cost-effective.

The city’s fleet of garbage vehicles includes 19 automated trucks, each costing about $200,000. Drivers use a direction control to extend a crane-like arm and lower it over its prey, the trash cart. The push of a button constricts a circular grip around the cart, which is then picked up and overturned into the truck’s hopper. The hopper holds up to 31 cubic yards of solid waste.

The process creates constant turbulence in the truck’s cab, which has two seats, each equipped with a steering wheel, pedals, and controls. Washington sits on the European driver’s side, propped at the edge of her seat and barely peeking over the wheel. Though onboard cameras offer views from the arm and rear of the vehicle, Washington looks over her shoulder to see what she needs to grab.

She can even tweak the control stick while lowering a dumped cart and close its lid before depositing it gently back in place. Washington is a past champion at the Memphis Solid Waste Department rodeo, which means she lassoed and dumped more carts with her mechanized arm in less time than any other competitor.

“I love this truck,” she says. “Wouldn’t trade it for the world.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Vera Washington

Though she wouldn’t part with the truck, the carts she could do without. “The city needs new, better carts. These are the same since 1980, and they’re so thin.”

Her Tuesday route in Frayser covers about 400 homes. Other days she’s in Raleigh, Senate Hill, and Spring Valley, off Highway 51 toward Millington. During the shift, supervisory types buzz up in city vehicles to pass a slip of paper scrawled with a missed address, helping ensure that Washington and other crews achieve the 100 percent satisfaction they strive for each day.

Washington’s lengthy tenure in the job provides a unique perspective on the city and how its residents and their habits have changed over the last three decades.

“People waste more than 30 years ago, but [garbage crews] go out less, too. People didn’t throw away food and clothes,” she remarks as she drives past a dozen curbed bags bursting with old clothes.

From her vantage point, she also sees challenges facing the city as its ethnic makeup diversifies.

“Mexicans make so much garbage, and they don’t recycle. If the city could get them to recycle, they’d make so much money,” Washington says. “I asked if [the city] could write a flyer in Spanish. These people just don’t understand what we’re doing.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

She says she has experienced no problems getting jobs or promotions because she’s a woman and sees nothing remarkable in her situation. Still, she expresses her share of gender pride: “Anything that a man can do on a job, a woman can do.”

Washington hopes to earn a promotion to the last link in the garbage chain: as a driver of one of the tractor trailers that hauls garbage to the BFI landfill near Millington. (The city also rents a BFI landfill in South Memphis that receives more tonnage than the north facility.)

The tractor-trailer picks up where the garbage truck leaves off — at the transfer station at the Bellevue solid-waste installation. The transfer station is built on the side of a steep embankment. At the west end of the building, on top of the embankment, are three ports for garbage trucks to back into after completing their routes. They drop their haul down a chute, which falls about one story down into a compactor. Tractor-trailers back into the three ports on the east, or bottom end, of the building, throw their back hatches open, and clamp onto a compactor. The compactor’s machinery rarely requires oiling, thanks to our greasy discards. It pushes garbage to the front of the trailer, recoils, and repeats.

The tractor-trailer holds about 80,000 pounds, or 2.5 loads from a neighborhood route truck. Ben Jones, 69, has driven a tractor-trailer for 35 years and worked for solid waste for 43.

“I was here when [Martin Luther] King came in,” he says. “I was in the strike all the way. I got tear-gassed three times, whupped twice, and went to jail.”

Jones was born and raised in Millington and hauled cotton in a tractor-trailer from the field to the gin before starting his job with the city, “so I already knew how to drive when I got here,” he says.

He wears thick-soled, steel-toe boots, which came in handy recently when he stepped on a plank full of nails at the landfill that stuck to him like a ski. “People don’t think [this job] is nothing, but I’d like for them to come out and drive awhile,” says Jones. “It’s pretty rough out at the dump. We’re out there in heat, mud, cold.”

Because of his seniority, Jones drives the newest of the fleet’s 12 tractor-trailer trucks. This one has a body by Sterling and an engine by Mercedes-Benz and cost $120,000. It’s one of four air-conditioned vehicles in the fleet and the only one with automatic transmission.

At the BFI North Shelby landfill, Jones gets in line at the weigh station behind refuse vehicles from a variety of carriers. Jones’ rig tips the scale at 79,300 pounds this trip. BFI charges the city $372 for this load.

The two BFI landfills the county uses stored 1.4 million tons of solid waste in 2005. The county generated just over 2.5 million tons of solid waste, but through recycling and diversion, reduced its landfill storage.

Jones winds through mounds of grassy land. He explains that the mounds are piles of trash and earth, grassed over. Each mound represents about three years of dumping. They build up to 120 feet high. The 959-acre landfill has used 167 acres so far. Estimates for its useful life range from 10 to 12 years according to Jones, to 30 years according to Collins, to 50 years according to BFI administrator Larry Hubbard.

At the dumping ground, trucks add to piles of garbage, some 15 feet high. The earth shakes underfoot as bulldozers spread the piles and then flatten the refuse into the earth.

Jones muses, “I’m just wondering — because I know I won’t be here to see it — what’s going to happen when this place fills up? Where’s the garbage gonna go?”

The landfills are a “permanent, final resting place for solid waste,” according to Collins. “They’re highly engineered, lined landfills, not something that’s going to leak,” he says. They are designed and regulated by state environmental agencies and the Environmental Protection Agency.

While garbage disposal consumes most of the solid-waste department budget and creates the most difficult environmental challenges, recycling offers solutions to both dilemmas. In Memphis, municipal recycling generates revenue. Participation, however, has been down since the city pulled the plug on the program for three months last year.

“We were setting records every week until the layoffs,” says Andy Ashford, recycling and composting administrator for the solid-waste department. “We’re back and collecting recycling every week.”

Now that the budget crisis has been averted, the system is running at near full-strength, and the solid-waste staff is working for solutions to the many other challenges they meet.

Frederick Redding, 46, by his admission, “ain’t the bullshittin’ type.” As the zone supervisor says, “100 percent total quality service and the safety of my crews are the two most important things. It has to be on the up and up.”

He follows the garbage and recycling trucks, observing the crews and looking for missed stops. He takes a customer-service approach to the job. Like Washington, Redding has climbed the solid-waste department ranks. He was hired three times as a temporary worker before he finally caught on to the back of a garbage truck 20 years ago.

“I’ve been crew person, crew chief, driver, acting supervisor, and finally, supervisor,” he says.

Redding begins each morning at 7 o’clock roll call at the department’s Scott Street station. He supervises garbage, recycling, and trash (primarily greenery and light construction refuse) trucks. Though each truck constitutes a team, someone inevitably fails to show, leaving Redding down a crew member here or a driver there. He moves crew members around to compensate. He has eight crews in a zone at full strength. Zones vary in size; some have four routes (400-450 homes each), some six. Some zones are larger than others, depending on the neighborhood plan and size of the lots.

“If we’re short one person,” he says, “we all have to step it up.”

Communication and visibility are Redding’s keys to success. If a truck has mechanical problems, he has to arrange a repair or a replacement as quickly as possible. If a customer has a complaint, he likes to address it within minutes. He carries a rake, shovel, broom, and replacement recycle bins in the back of his pickup truck just in case.

One of Redding’s two cell phones rings. It’s one of the three employees he’s missing this day. Though the absence translates directly into more work for Redding and those who show, he sees the big picture. He listens calmly, reassures the employee that they have followed the proper procedure for medical leave, and encourages the employee to take the needed time to fully recover.

“The crews have to feel important,” he explains. “I let them see that they’re needed. I’ve been a garbage collector, a recycle driver … and I know how the crews feel. I have a lot of respect for these guys and ladies.”

It shows in his conversations with them. He refers to female employees as “ma’am” and males as “good man.” “If they’re feeling good, they’re working hard, and everybody profits. My job is easier, their jobs are easier, and the customers get good service,” Redding explains.

Meanwhile, a voice crackles over Redding’s CB, telling him about a truck headed off its route to get a small but essential repair. He calls the driver of the wounded truck and then the mechanic back at the station to inform each what to expect from the other. A half hour later the two, separately, call Redding back within moments of each other to tell him that the repair is complete. He compliments the mechanic before signing off. “Next time I have to send a truck to him, he’ll remember that,” Redding says.

It’s similar with his customers. Redding documents every problem. Driving through his zone, Redding can point at a house and tell you something the resident complained about six months ago or describe their disposal habits in detail. “I make a habit of trying to be perfect. These people pay us for the service, and you have to give your all for them,” he says. “If I get a call that garbage was missed, I’m out in the zone, and in five minutes I can get that taken care of. You go there the minute you get the call.”

To prove the point, he stops his truck and jumps out to grab a discarded tire from the curb.

Like Washington, Redding’s job connects him to diverse elements of the city. Monday and Tuesday, the crew works Orange Mound and Castalia Heights in South Memphis. Later in the week, the group moves east along Walnut Grove Avenue. “The further east you go, the more diligently people recycle,” Redding says. “They have a problem if you don’t pick their bin up by a certain time.

“Even after trying to sell this thing, on certain streets I see no recycle bins,” Redding says. “I go door to door, tell them, ‘Take this recycle bin and show me what you got tomorrow.’ There needs to be more information about how important recycling is. If you know that certain areas don’t recycle, you should focus on that zone and do whatever it takes to get these people to recycle. You can still go to the landfill and see things that should be recycled. … If you believe in something, you won’t be afraid to lift your voice up like a trumpet,” says the part-time gospel singer.

Redding says the system works for the public, despite the room for improvement. “I’ve seen systems come and go. [This one] works to get taxpayers their money’s worth. I don’t hear many complaints from citizens. I don’t hear my crew say we need more trucks. All I hear is that it’s working.”

According to Ashford, the city recycled 27 percent of residential solid waste collected last year. The city services about 200,000 single-family homes and small apartment buildings. San Jose, California, a progressive recycling city that services a comparable number of homes, reports a 61 percent recycling rate. At the other end of the spectrum is Dallas, which reports a 7.7 percent recycling rate on 231,000 homes, according to www.wastenews.com. Memphis has the smallest of the three municipal solid-waste budgets and spends a little more than Dallas on recycling.

“We’re saving over $2 million a year in landfill fees,” Ashford says. “We’re one of the few cities in the country that achieves revenue.”

Ashford was hired from BFI in 1992 to implement the city’s curbside recycling program. He has seen the program expand from its beginnings in Scenic Hills and Cooper-Young. Not only has Ashford brought recycling citywide, he’s helped make it profitable.

“We went on a nationwide search and requested proposals from recycling companies, and we ended up negotiating FCR, out of Charlotte, North Carolina. They built a facility on our property [at the Farrisview solid-waste facility off American Way near Lamar Avenue]. Some cities have different types of contracts, but you need somebody who’s close with the commodity market. We’re looking to save the city as much as we can by not putting [waste] in landfills and saving the taxpayers,” Ashford says.

City recycling-collection vehicles unload on the west side of FCR’s hangar, and 18-wheelers from various buyers back up to ports on the east side of the building and load bales of sorted and compressed plastic, steel, aluminum, and newspaper for delivery to “end markets.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Inside FCR’s recycling facility off American Way

In Memphis, citizens can place their materials, unsorted, in their 18-gallon plastic bin and set it curbside for weekly pickup. Recycling crews presort the newspaper and mixed items by throwing them into separate hoppers on the truck. They dump their two loads on opposite sides of the FCR recycling facility. The pile of newspaper and junk mail at FCR stands as high and wide as a peak-roofed Queen Anne.

Things get a little complicated over on the mixed side. Material is spun through a rifled cylinder to separate it. It’s then moved up a conveyer belt, where a magnet pulls the steel cans from the rest. A line of pickers along the belt manually sorts pigmented, opaque, and clear plastic items and tosses them into their respective bins. When a bin fills, a chute at the bottom opens, and the materials are bulldozed to the facility’s baling system.

The glass pickers — standing back to back with the plastic pickers, on a narrow gangway about 30 feet off the ground — sort bottles by color. The glass is ground on site into different grades for different markets.

Baled paper, the most profitable and in-demand product the company sells, becomes pressboard, insulation, and recycled paper. Aluminum cans go back to mega-breweries like Anheuser-Bush.

The baling equipment crushes materials into big, colorful cubes, which are then loaded into 18-wheelers.

The biggest challenge at the sorting facility is contamination of non-recyclables in the stream of material. The worst offenders, according to Ashford, are those orange plastic newspaper bags delivered daily to thousands of Memphis doorsteps. Many dog walkers have discovered an appropriate reuse for the bags, but they are otherwise unrecyclable.

“These bags get in there and wrap around the gears of a machine and shut the whole place down,” he says.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Ashford picks through the mountain of newspaper to remove several pieces of cardboard and a flattened wooden bushel basket. Sorters must also be careful of glass in the newspaper pile, which, he says, can ruin an entire load of the commodity.

Recycled materials are commodities that fluctuate in price daily. Thanks to the FCR deal, the city profits tidily from its refuse. “We make $25 a ton, one of the highest rates in the country,” Collins says. With about 117,000 tons collected, the dollars add up.

Collins, 52, has led public works since 2000. “The [recycling] participation rate is not what we would like for it to be,” he says. “Less than a third of our customers recycle, but citizens save the city money by recycling — $2 million in landfill fees [last year].”

Ashford says, “People live disposable lives. Look at fast food. People want to consume and discard. But they control their own destiny as far as the cost of [waste-management] services.”

As for Vera Washington’s view that Spanish speakers aren’t getting the message about recycling, Collins says, “We’ve tried ads, mailers, TV and radio, and none of it has made a difference. The one thing that makes a big difference with the participation rate is the contest. It doesn’t cost the city much to carry out the contest, but word travels from neighbor to neighbor, and that’s the most effective method.”

The “contest” is the curbside cash giveaway that rewards residents for recycling and adds the incentive of a larger prize for team entries of two households. The concept behind the contest is one that Collins and Ashford believe in. Regardless of socioeconomic class or awareness of environmental issues, peer pressure can lead to greater participation. “People influence each other. Poorer, undereducated people still participate in pockets and influence their neighbors. Promotion and education are key,” says Ashford.

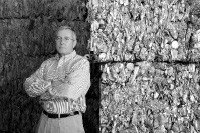

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Andy Ashford

Gesturing back to the FCR recycling facility, Ashford says, “We hope years from now, this building has to be doubled [in size]. We want to find new markets for recycling materials and avoid the cost of disposal. Manpower is always a challenge, and we have to save [budget] money, but the biggest challenge is to get people to do what they need to.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks