Jeff Bezos, owner of the world’s largest bookshop, famously defined a book as paper and binding. Then he made a fortune on the position that there is no good reason to actually pay a writer: The time involved to think up, write, and polish a book until your brain goes numb has no place on a spreadsheet. Daniel Ek, CEO of Spotify, helpfully suggested that a constant stream of singles, rather than carefully crafted albums, would generate more pennies for the musicians whose careers he’s wrecked. Twitter and Facebook have made communication so efficient that we can’t stand each other anymore.

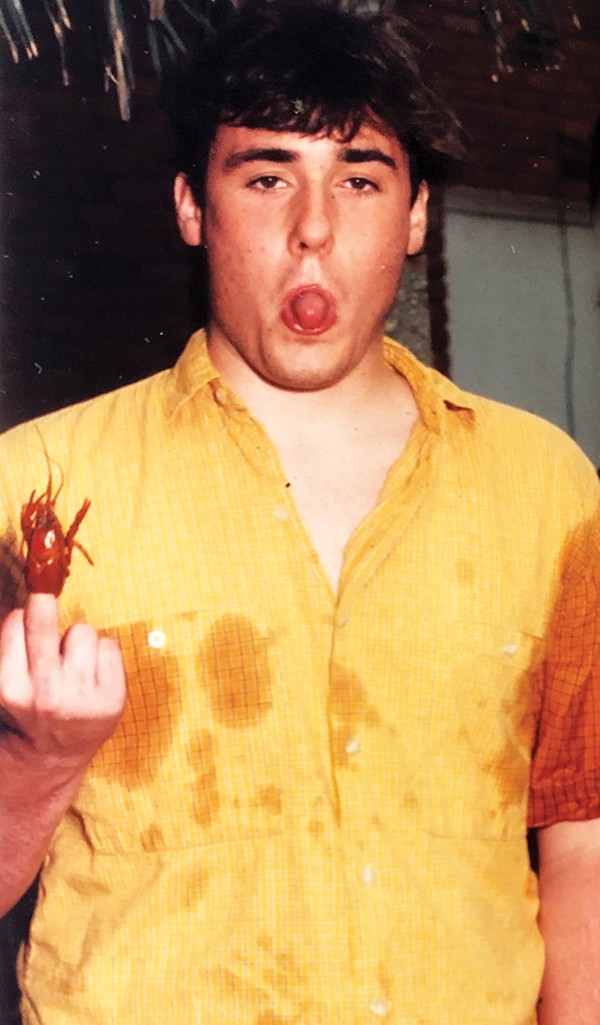

In a world swamped by data metrics, we’ve developed a fetish for efficiency. In a lot of ways that’s a good thing — engineering in modern cars leaps to mind. It’s also a tricky thing. Consider the American beer industry after prohibition, where a few large players dominated the market, determined to grow not on quality but efficiency. Each brewery chased the other’s market share by tasting more like the competition, which basically left America with two choices of fabulously cheap and nearly identical beers. For most of the 20th century, good ole American know-how made the United States the most efficient beer industry in the world. It was also the worst place in the world to live were you a beer-lover. Murffbrau’s heroic run in Tuscaloosa when I was an undergrad was not because I knew how to make good beer. The stuff was terrible, but it was different. I was also giving it away. I was also insane.

Richard Murff

Richard Murff

My point still stands — embracing a bit of inefficiency in order to make something a little different is what transformed the U.S. beer market from the worst place to be for a beer-lover to arguably the best in less than a generation.

I know more people who head to North Carolina’s beer tours than to Napa Valley these days. Sure, wine snobs can be insufferable, but because they were always going on about terroir and starlight and a bunch of other imaginary metrics, no one ever expected them to be efficient. Wine-makers are just expected to be vaguely French at heart.

Craft beer is a delicious monument to inefficiencies: small batch, jerry-rigged distribution, and you might see the person who made it at the gas station. Yes, beer people can get as snobby as the wine crowd, but just ignore them. And sure, you get the odd swing-and-a-miss, but that’s part of the fun. Besides, a miss isn’t always a miss. I’ve definitely softened my stance on gose beer. For this week’s suggestion, I had a High Cotton Scottish Ale, because the unseasonably cold and cloudy weather (it was 88 degrees) put me in the right state of mind. The stars lined up here; it’s a great Scottish Ale, what can I say? It just tastes inefficient. It’s malty, with a bit of caramel and toffee, but clean. This is important because the mid-80s isn’t really all that cold. I’ve been in the back room of High Cotton. You could eat off the floors back there, but it is not a monument to economies of scale.

Even the distribution of craft beer is wonderfully slipshod if you go by the offerings of the local growler shops around town. And that’s the fun part: Put on your gas mask, secure a six-foot perimeter bubble, and say in a loud, clear voice: “Hey, guy, gimme the weirdest thing you’ve got!” Then say it again because chances are he didn’t hear you because your mouth was covered.

Go home, pour a pint, and read a book or listen to music, written by someone who actually thought it out. Or think something out your own damn self. No, it’s not very efficient, but beer is a pretty inefficient way to go about getting gassed. If that’s the goal, you’re better off quaffing vodka.

Richard Murff

Richard Murff

Richard Murff

Richard Murff  Richard Murff

Richard Murff

Richard Murff

Richard Murff