Twenty-two years ago, Congress put sanity up for a vote. Sanity lost in the House, 420-1. It lost in the Senate, 98-0.

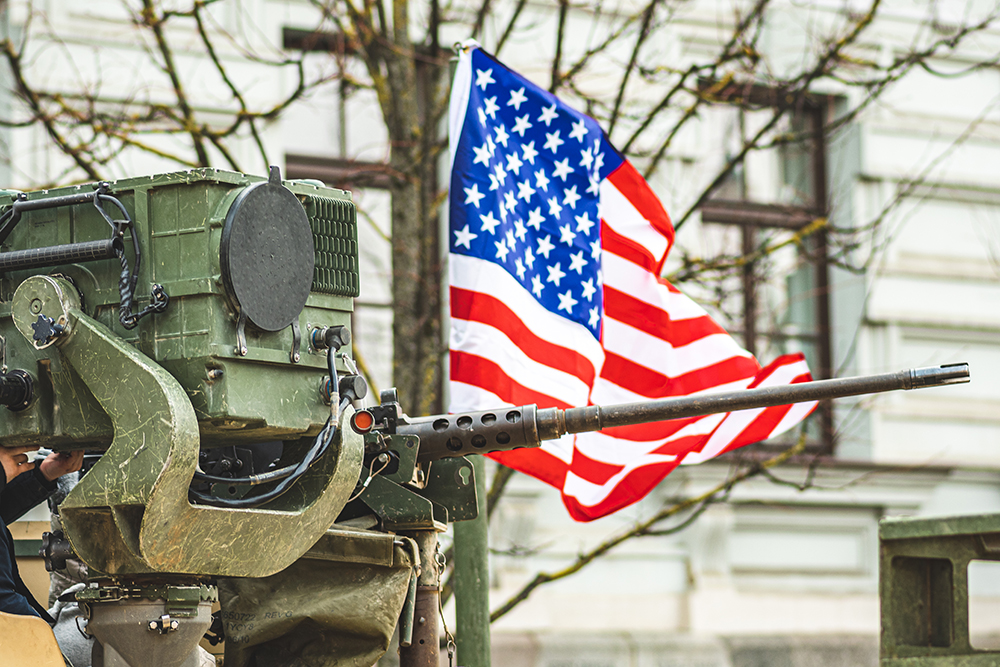

Barbara Lee’s lone vote for sanity — that is to say, her vote against the Authorization for the Use of Military Force resolution, allowing the president to make war against … uh, evil … without congressional approval — remains a tiny light of courageous hope flickering in a chaotic world, which is on the brink of self-annihilation. Militarism keeps expanding, at least here in the U.S. If there’s a problem out there, option one is to kill it quickly. Problem solved! This simplistic (and utterly false) mindset, which is always present — the companion of fear — may have a grip on American politics like never before, as demonstrated in the recent debt-ceiling standoff, in which President Biden came to an agreement with the Republicans that social spending will be slashed but “defense” spending must continue to expand.

You know. It’s the only thing that’s truly crucial. Poverty? Collapsing infrastructure? Underfunded schools? Climate disaster? We can worry about that stuff later, but as House Speaker Kevin McCarthy explained to reporters recently: “Look, we’re always looking where we could find savings … but we live in a very dangerous world. I think the Pentagon has to actually have more resources.” In other words, the U.S. is not a country with the maturity to discuss and analyze complex issues, such as the future of the world. Hey, it’s dangerous out there! It’s full of terrorists and dictators. That’s all you need to know. “Weak on defense” is the equivalent of “wants to defund the police” — a politician’s death sentence by advertising. No matter how much hell war creates — no matter how many families it displaces, no matter how many children it kills — we’ve got to be ready to wage it, you know, whenever we feel like it. And the mainstream media, in its basic coverage, doesn’t question this or delve into a complex analysis of the world.

But we are still a country that is slowly and complexly evolving — no matter that the powers that be, for the most part, don’t know it. Let’s return to that AUMF vote, passed in the wake of the 9/11 devastation. Barbara Lee, whose father was in the Army, serving in both World War II and the Korean War, knew about the human costs of war. After 9/11 she was deeply uncertain what the nation’s immediate response should be. She attended the memorial service at the capital, held the day of the vote (and attended by four former presidents plus the sitting president, GWB). There, as she told Politico, the Reverend Nathan Baxter, as he led the attendees in prayer, called on the nation’s leaders, as they considered how to respond, to “not become the evil we deplore.”

His words struck her in the soul. She had planned to challenge AUMF — she saw serious problems with it — but now she had certainty. She edited her prepared speech as she returned to Capitol Hill. There, she told her colleagues, “There must be some of us who say: Let’s step back for a moment and think through the implications of our actions today. I do not want to see this spiral out of control.” She had no idea — until the vote began — that she’d be the sole member of Congress to vote against AUMF. And soon enough her office was flooded with calls and emails. They were both for her and against her, but many of the latter were vicious. She was called a traitor. She received death threats. Plenty of people, especially as the antiwar movement grew, also declared, “Barbara Lee speaks for me.” But the fury of those who hated her vote, who were shocked that she had the audacity to speak the truth, demonstrate the self-feeding loop that war creates. Instantly, all complexity vanishes and you’re either for us or against us. And if you’re against us … uh oh. Watch out.

She also told Congress that day: “We must be careful not to embark on an open-ended war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target.”

These are not the sort of words that status-quo America listens to, even in retrospect. My God, 20 years of war in Afghanistan, eight years of war and unspeakable carnage in Iraq. The U.S. was the official loser (though not its military-industrial complex). We’re not any safer; we’re way less safe. But it’s all dismissed with a shrug. “We live in a very dangerous world.” All we can do is keep upping the military budget and keep refusing to listen to Barbara Lee.

When will this change? The collective psychology of it goes pretty deep. Perhaps the presence of war in the national psyche bears a relationship to the presence of guns. The United States, as Scientific American pointed out, is “the only country with more civilian firearms than people,” which, according to researcher Nick Buttrick, is a phenomenon that began in the American South after the Civil War.

Guns had been tools, handy in rural areas for pest control. Then came the Emancipation Proclamation. Previously enslaved people — “property” — were suddenly free. They even had some political power. The world was no longer what it once was; the established order was gone. The world, from a white perspective, was suddenly chaotic, dangerous, incomprehensible. And white people were no longer on top. Gradually guns became fetishized as sources — and symbols — of strength. “Through your weapon, you could recreate order,” Buttrick said.

Is that not the American way? All you have to do is disconnect the consequences from the trigger, and you can keep pulling it and pulling it.

Robert Koehler (koehlercw@gmail.com), syndicated by PeaceVoice, is a Chicago award-winning journalist and editor. He is the author of Courage Grows Strong at the Wound.

Rfischia | Dreamstime

Rfischia | Dreamstime