By the time you read this, we will have celebrated a national holiday commemorating the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. King was a civil rights pioneer, a champion for nonviolent struggle toward equality and justice, and an outspoken critic of the United States of America. He was a visionary whose idea of the American future was radical during his time, and that vision remains radical today.

Many of us, even people reared on Memphis’ soil, even people old enough to remember the thunderclap of his assassination and the void that followed, have softened our view of Dr. King and his ideologies. We see his legacy of civil rights activism as something of the past, and the injustice that he opposed as a historical blot on the American tapestry that we are quickly rubbing away. After all, because of the efforts of Dr. King and other activists, we now live in a post-racial country. Our collective work to end racism has borne fruit, and discrimination no longer exists within these borders. The American dream has been realized.

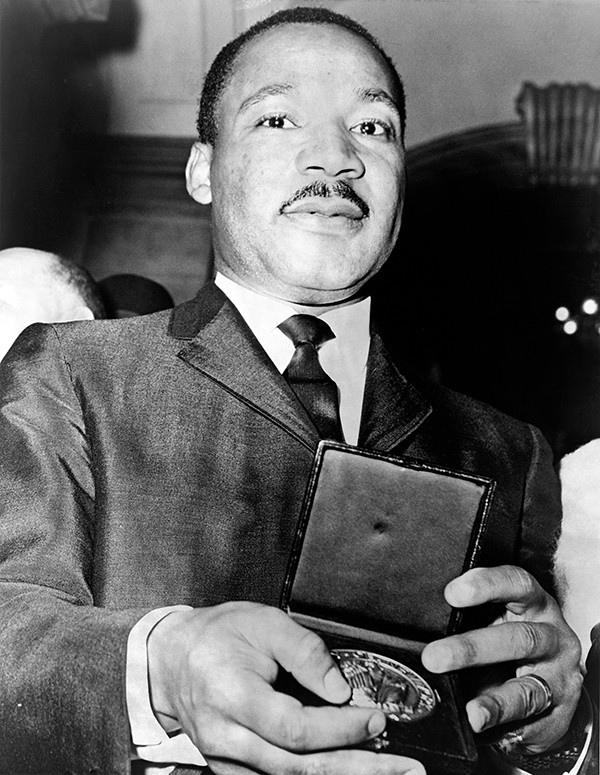

Phil Stanziola, NYWT&S staff photographer courtesy wikimedia commons

Phil Stanziola, NYWT&S staff photographer courtesy wikimedia commons

Martin Luther King Jr.

Except it hasn’t. We owe both Dr. King and the day we observe in remembrance of him more respect than a blind sweep of his teachings and legacy beneath a sheet of self-congratulatory misinformation. This is just as true in Memphis as it is anywhere else.

Legislation in favor of a national holiday recognizing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was first introduced by Congressman John Conyers (D-MI) in 1968, four days after he was assassinated. Originally envisioned as a call to continue Dr. King’s unfinished work, the fledgling national holiday faced constant congressional roadblocks, and legislation supporting it was routinely defeated by officials who cited King’s possible communist ties, his extramarital affairs, and — unofficially — good old American racism as reason enough against any formal recognition of his life. After Herculean efforts from those who supported the holiday, including a multi-million-signature petition from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, endorsement from Chicago mayor Harold Washington, several congressional testimonies from Coretta Scott King herself, and a Stevie Wonder protest song, the first national King Holiday was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1983 and finally observed in January 1986. Only 17 states celebrated the first national King Holiday, and it wouldn’t be recognized as a federal holiday in all 50 states until 1999.

During the holiday, many citizens, including thousands in the Mid-South, participate in some form of volunteerism in the spirit of Dr. King’s statement that “everyone can be great because everybody can serve.” But Dr. King referred to a more lasting sort of service than we allow for in our decontextualized take on this quote. In “The Drum Major Instinct,” the sermon that this quote is lifted from, he discusses serving humanity as Jesus did, with love and with a heart turned toward complete justice for all humankind.

“Say that I was a drum major for justice,” Dr. King said, referencing in this sermon his commitment to transformative economic justice, to ending American imperialism, and to grounding his activism in a true and total love of all oppressed people and a desire for their well-being that dove deeper than the political. Dr. King died fighting for economic and social justice for workers and ending wars as well as for racial justice. He fought for a lasting state change for America, not for his image and philosophy to be warped in order to serve the liberal-guilt industrial complex. It is easy for us, on the national holiday and throughout the year, to pretend to act in service to Dr. King’s life and teachings, but if we are not truly committed to transforming the lives of others, to, as Dr. King said in the closing of his sermon, making “this old world a new world,” then what are we doing?

A commitment to transformative change in this city means a commitment far beyond a weekend volunteering spree. It means fighting day in and day out for those Memphians who find themselves economically and socially dispossessed. It means committing ourselves to an intentionality of vision that includes recognizing that our city faces a complex network of intersectional challenges. It means devoting ourselves to interracial and intercultural inclusivity in more than just our social network feeds. It means challenging ourselves on the very ideas that our country is built on, and determining for ourselves whether we are truly working toward the ideas and moral vision that Dr. King presented to us when we enable systemic ills like mass incarceration, economic injustice, and inequality in housing and transit access to disproportionately hinder certain members of our community.

Four days after we celebrate the legacy of Dr. King, we are swearing into the office of the president a temperamental toddler of a man whose every action sends many Americans sliding into deep depression and anxiety. Most of us assume that if we were to resurrect Dr. King in a post-Trump inauguration America, he would find himself appalled to the point of returning to his eternal slumber. But would he be less appalled by the America he would have found himself in four years ago, during the presidency of a man touted as the literal representation of his teachings? We must ask ourselves: Have we really been working in service to Dr. King’s dream of visionary, transformative equality, or are we just pretending?

Troy L. Wiggins is a Memphian and writer whose work has appeared in the Memphis Noir anthology, Make Memphis magazine, and The Memphis Flyer.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks