HAVANA — It’s difficult to pinpoint the exact moment when I fell in love with this place. Was it when I zip-lined over the treetops at a coffee plantation that had been turned into a national park? Or when, drenched in sweat, I struggled valiantly to keep pace with a salsa teacher’s swiveling hips and quick feet?

It could have been during a visit to the Museo Nacional de la Campaña Alfabetización, a tribute to the successful 1961 literacy campaign. Or perhaps it was the Cuban coffee at every meal — and in the evenings, the smoothest rum I’ve ever tasted.

The Museo Nacional de la Campana Alfabetización, the national literacy museum

Just a few days into a weeklong trip, I swore to myself that I would be back. I was in one of the first Memphis groups to visit Cuba after the December 17th announcement by President Obama that U.S.-Cuban diplomatic relations would resume for the first time in more than 50 years.

Travelers enjoying a cigar

In March, the University of Memphis’ study abroad program sent just over a dozen students and community members to Havana. Dennis Laumann, an associate professor of African history, led the group, many of whom were enrolled in his Afro-Cuban history class.

The December announcement meant that we could bring back up to $100 worth of Cuban cigars and rum, souvenirs that were previously forbidden by U.S. restrictions.

A Flamenco dancer

If you’ve traveled to other Latin American or Caribbean countries, Havana will feel familiar. There’s the warm weather, the rain showers that last only moments, the pastel-painted buildings, and supper-time staples of rice and beans.

But when the world’s richest nation forces a smaller, developing one into an economic corner for decades, the poorer nation struggles to thrive. Proof of the struggle surfaces in the crumbling facades of once-beautiful homes and the scarcity of retail outlets where you could practice consumerism and capitalism.

For me, and I suspect, most generations that have no memory of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis or the Cold War, the U.S. isolationist strategy served mostly to create a mystique about the island.

Forbidden fruit always tastes sweeter. And Cuba was delicious.

Here are some highlights from the trip:

The Cars

If you close your eyes and think of Cuba, chances are your mind will produce an image of a 1950s-era, hulking American sedan. Rows of cars just like that greeted us in the parking lot at José Martí International Airport.

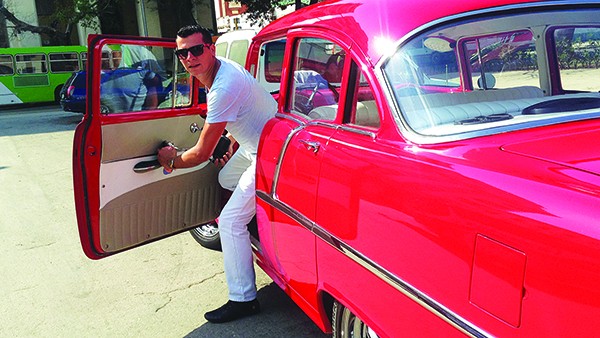

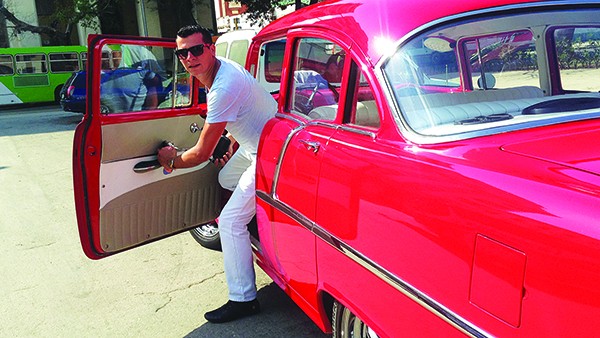

A 1950s-era car in pristine condition

Although they may appear to be in mint condition, the only original part is the body, said Rodrigo González, the Cuban program coordinator for Girasol Study Abroad. The cars are “museums on wheels,” he said, and the owners must be magicians to keep them running.

Antique cars shared the roads with Korean-made Kias and boxy Lada sedans, Russia’s version of the Volvo. Many of the cars double as taxis, although they may not be marked as such.

Our taxi driver, Hendry Lago

For about $5 Cuban convertible pesos (the dollar exchange rate is about 1:1), Hendry Lago transported two fellow study abroad travelers and me from Old Havana to our hotel in a gleaming, candy apple red 1955 Chevy.

The seats were covered in pristine white and gray leather and the chrome trim sparkled like the car just pulled off the lot. But on the dash was a very modern touchscreen sound system and under the dash, an air conditioner strong enough to fight Havana heat.

Lago looked like he stepped off the set of Grease with his slicked-back hair and snug jeans. He took the scenic route, cruising down the Malecón, the road that curves along the coast. As he drove, Meredith Kaback pulled a tube of red lipstick from her purse.

The occasion called for it, she said, passing the lipstick to me. I agreed.

The wind was in our hair, the sun warmed our skin, and our lips matched the car. I was smitten.

Cigars

Our tour included a trip to a cigar factory. From the street, the H. Upmann cigar factory, founded by Germans in 1844, was indistinguishable from surrounding buildings.

Our tour guide, Idalmy, told us in her no-nonsense tone: No cameras, phones, or bags were allowed inside. We must stay together — no wandering off (as some of us were prone to do).

Once inside, the cigar factory guide led us up a flight of stairs. He steered us into a long room lined with rows of desks. Bent over the desks were men (and a few women) with stacks of flattened tobacco leaves in front of them. Many of the workers wore ear buds to listen to music on their cell phones. To help pass the time, the factory hired someone to read the newspaper to the cigar makers, the guide said.

The most experienced rollers make the bigger cigars, laying leaves on top of each other and sealing them together with a vegetable-based glue.

In another room, women sat with piles of dampened leaves. With one fluid motion, they stripped the stem from the middle of the wide leaves. No men would want to do this work, our guide told us. This job was for women only. (This was said with no awareness that his remark was sexist.)

In Cuba, cigar factories are state-run. Between 10 to 20 percent of the profit goes to the farmer and the rest goes to the government. No cigars were sold inside the factory, but an overcrowded, small store nearby offered Cuban rum, coffee, and several kinds of cigars, including the Cohiba and Montecristo brands.

The other tourists were surprisingly aggressive, shoving other shoppers out of the way, but I put my Memphis on and muscled my way to the counter.

Cuisine

If there was one disappointment, this was it. With rare exceptions, the food was mediocre.

Breakfast at Hotel Paseo Habana was your standard fruit, fruit juice, eggs, and toast. I followed the advice from TripAdvisor reviewers and ordered French toast, which was tasty the first morning, but not so much after that. Ask for syrup and you got a crystalized pat of honey.

One standout: Doña Juana, a paladar (privately owned, not state-run restaurant) on the top floor of a home in the Vedado neighborhood.

Half of the study abroad group walked there one night, where we had the terrace to ourselves. The menu was in English and Spanish. The server was pleasant and patient as he took our orders.

If you want to impress people on the cheap, this was the place to go.

When the server showed up with shots of Havana Club rum for everyone, I waved him away, thinking he’d brought the drinks to the wrong table.

One of the community members in our group announced that he’d ordered the liquor for us and we all cheered. I thought to myself: He must be rich. Then I looked at the menu again: Seven shots set him back about $7.

For $20, you could get a perfectly cooked lobster dinner with generous portions of rice, black beans, and salad.

Also worth trying: the Las Terrazas coffee at the former coffee plantation (now national park and biosphere reserve) that bears the same name. This small cup of coffee, cacao liquor, milk, and ice was chocolate happiness.

Art

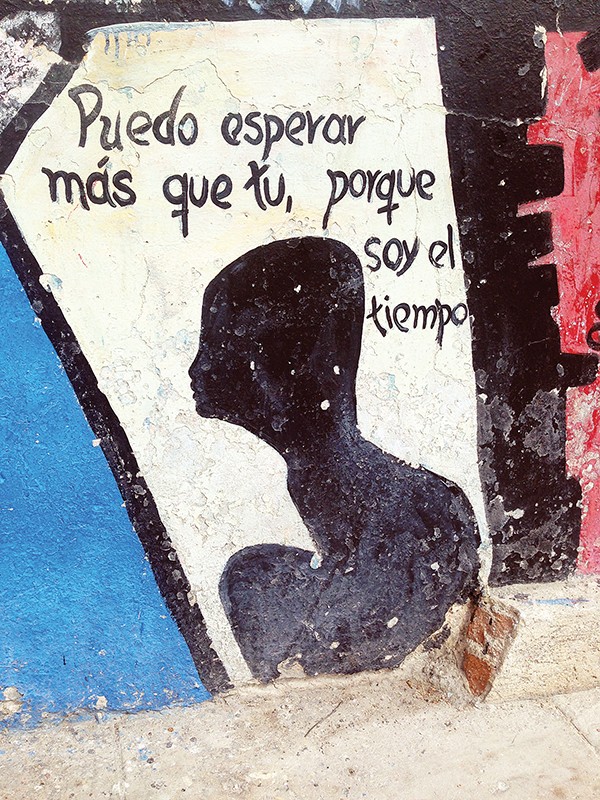

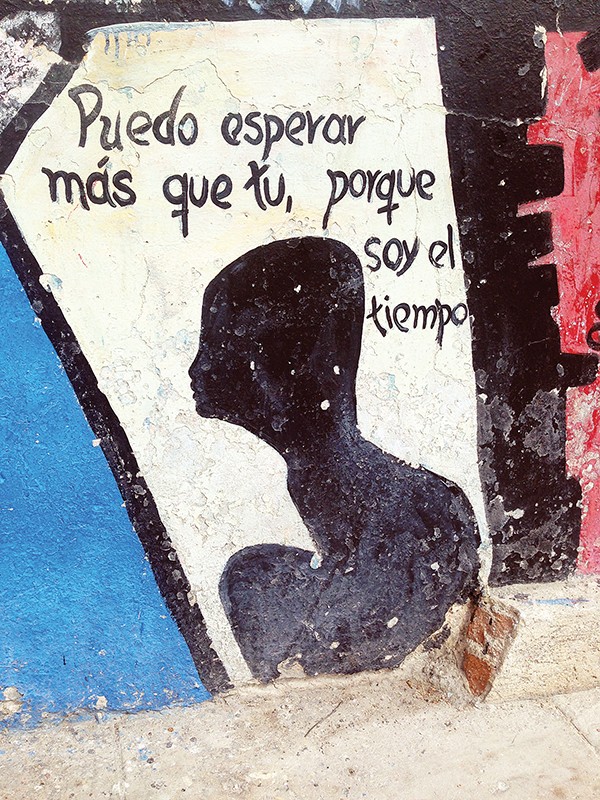

Callejón de Hamel is a short alley devoted to Afro-Cuban culture, art, and music in the Havana Centra neighborhood. Much of the art is made of found objects, such as the old bathtubs cemented into walls. On the bottom of the tubs were poems, which were often political in nature.

Found-object art in the alley of the Callejón de Hamel, which showcases the Afro-Cuban culture.

“Grandma, why do the towns fight?” began one poem of a conversation between an elder and a child. “For love and respect.”

“And the powerful?”

“For gold and leisure.”

On top of a building that overlooked the alley were two water tanks, one labeled “Agua Blanca” and the other “Agua Negra.” It was a social commentary on the absurdity of racism, which several Cubans proudly claimed no longer exists in their country.

The revolution did bring a formal end to segregation, but scholars we talked to acknowledge that the stains of racism remain. They point out that the faces tourists see are more likely to be white. And since most of the Cubans who fled for Miami are also white, it is their relatives who benefit from remittances sent from the states.

In the Jaimanitas neighborhood, artist José Fuster had turned his community into a wondrous, tile-covered paradise. Although Fuster was out of town, we had lunch in his dining room and spent about an hour marveling at the fanciful sculptures he’s created in his courtyard and along the walls that line sidewalks.

His painting style has earned him the title “Picasso of the Caribbean.” Less than a block from his house, he erected a tile rendering of Hugo Chávez, superimposed over the Cuban and Venezuelan flags.

History

When I asked fellow travelers what their favorite part of the trip was, I expected them to gush over the old cars or maybe the tour of the coffee plantation, where we saw the stone outlines of slave quarters and some of us went zip-lining. But without exception, they were most impressed by the Museo Nacional de la Campaña Alfabetización, the national literacy museum.

The small one-story building holds artifacts associated with the 1961 literacy campaign. In a 1960 speech to the United Nations, Fidel Castro declared that Cuba would be the first nation that “will be able to say it does not have a single illiterate person.”

The next year, more than 250,000 literacy tutors, at least 105,000 of whom were between the ages of 9 and 16, went from cities to rural areas, living and working alongside the farmers during the day and, at night, teaching them to read.

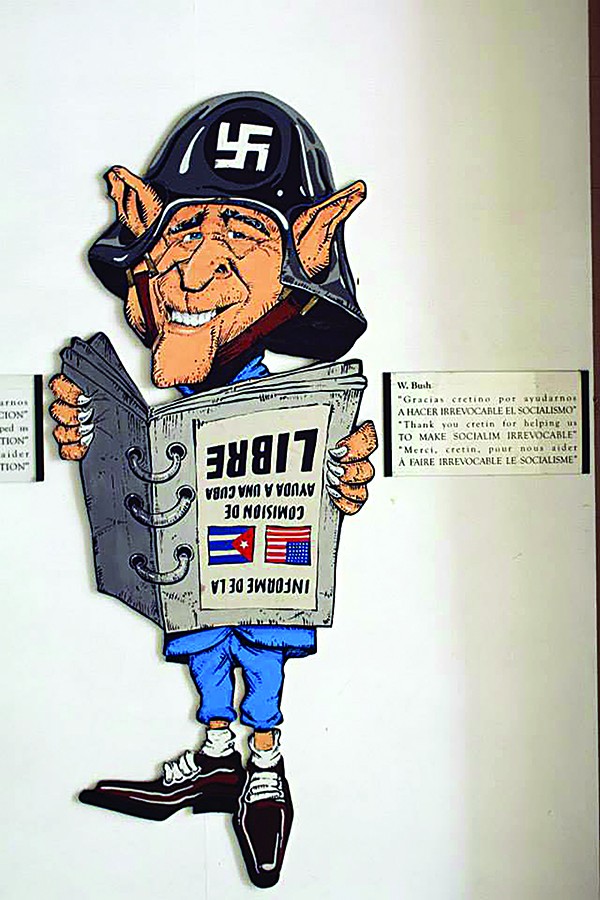

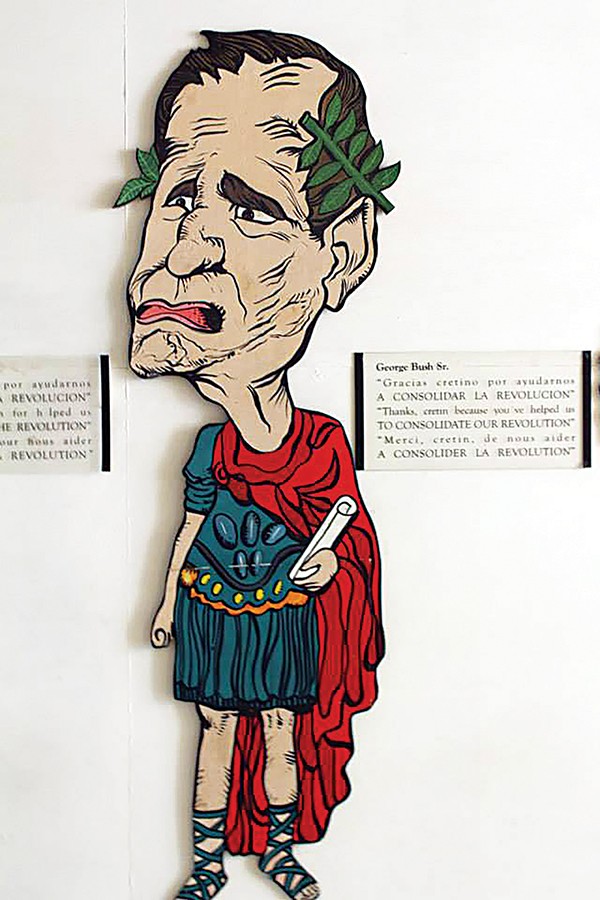

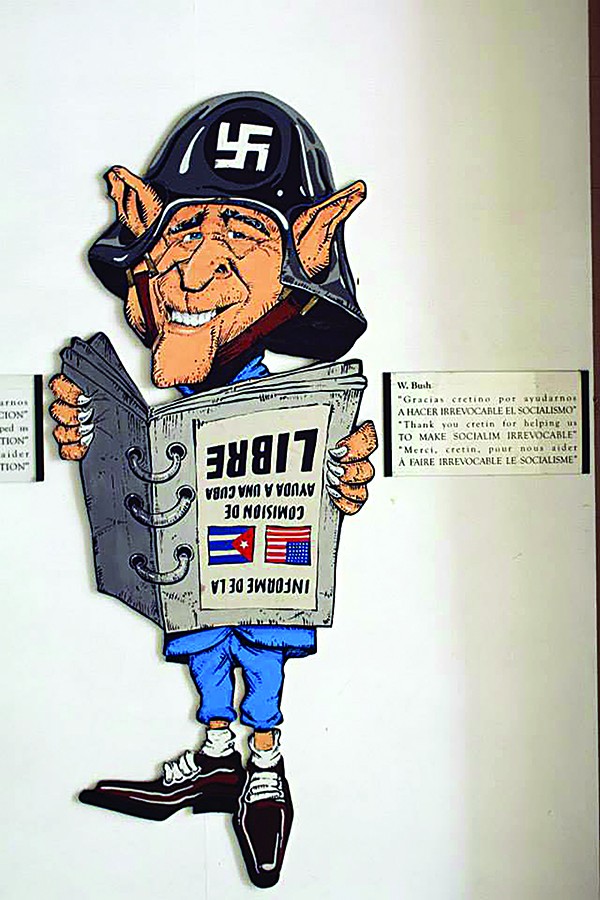

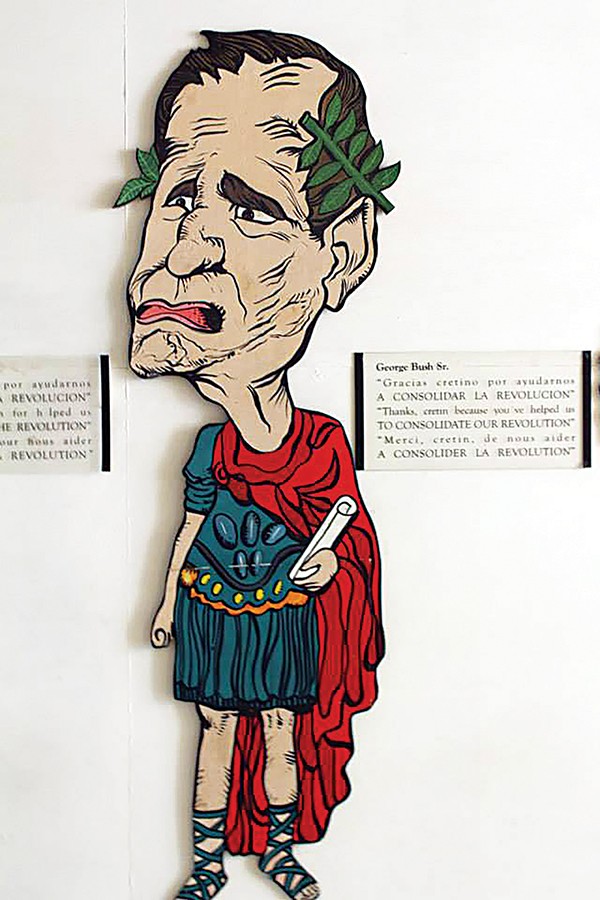

Caricature art showing the animosity between Cuba and the U.S. in the Rincon de las Cretinos.

In a single year, museum director Luisa Campos told us, the illiteracy rate fell from 23 percent to under 4 percent. (The adult illiteracy rate in Cuba today is less than .2 percent, compared to 14 percent in the United States).

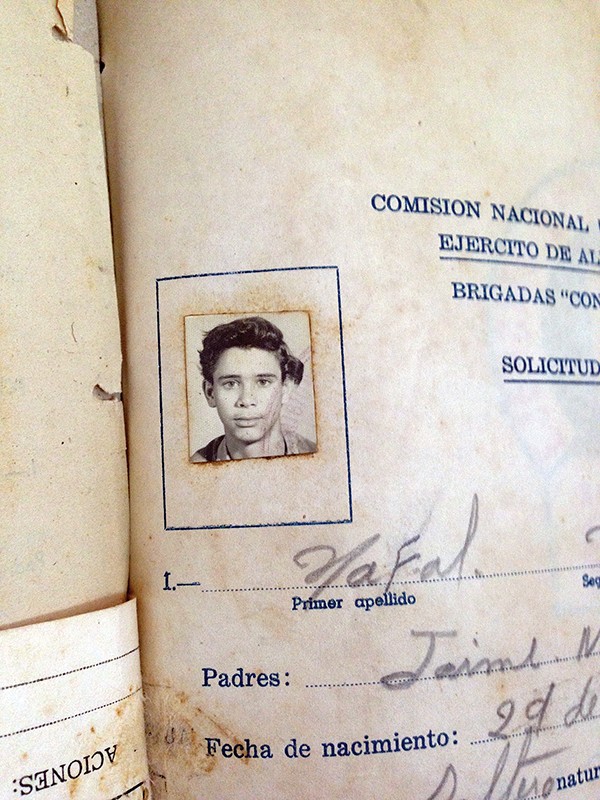

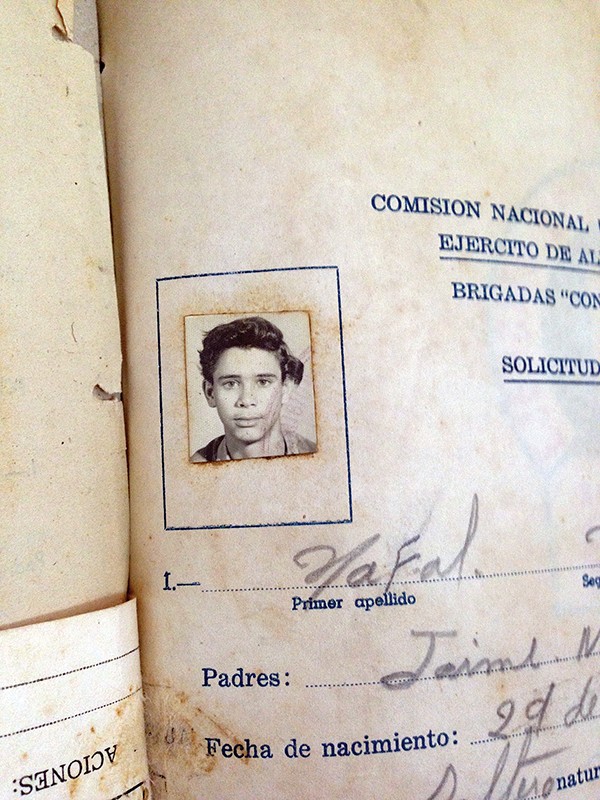

Campos asked Nafal Valdes, the quiet, unassuming bus driver who shuttled us around town, to come to the front of the museum classroom.

volunteer

Valdes, Campos told us, had been one of the literacy volunteers. She opened a thick, yellow register book to the page with a tiny black-and-white photo of Valdes at 16.

As we stood and applauded, Valdes wiped away tears.

“When you look at any society, it’s what that society places value in that really defines it,” said Luther Mercer, the managing director of programs for New Leaders, a national nonprofit that develops school leadership.

There are no interactive exhibits at the literacy museum or at the Museo de la Revolución, housed in the stately presidential palace last occupied by ousted Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. Instead you’ll find stunning architecture, elaborate murals, and stone tributes to beloved revolutionaries Castro, Ché Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos.

A first-floor museum hallway held the only blunt testament to the animosity between Cuba and the United States I saw. In the Rincon de las Cretinos (the corner of cretins), were caricatures of Batista and U.S. Presidents Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush. The denouncements are in English, Spanish, and French.

“Thank you, cretin,” reads the placard next to W’s caricature, “for helping us to make socialim [sic] irrevocable.”

The enmity doesn’t extend to Cubans, who were, without exception, warm and friendly.

Our group spent a lot of time talking with members of Proyecto Espiral, a grassroots community project committed to sustainable development led by young adults.

“They were all very proud of who they were as Cubans,” Mercer said.

And yes, we could talk to whomever we wanted, about whatever we wanted. Before I went to Cuba, I’d been warned to look out for “watchers” who would eavesdrop on our conversations, listening for anti-socialist musings.

Before graduating senior Aukina Brown left on the trip, her friends were full of baseless warnings. “They said our plane would disappear; Fidel Castro wouldn’t let us come back — all kinds of stupid stuff,” Brown said.

But I never had the sense that we were being watched. Most police don’t even carry guns. We walked for blocks and blocks at night and barely generated a catcall.

Granted, the window A/C units at the hotel were loud and the towels scratchy. We had no access to the internet — and I didn’t miss it a bit.

It is hard to remember to throw toilet paper in the trash, not into aging septic systems. Paying the bathroom attendant to get a few squares of toilet paper got old.

“Don’t compare everything to America when you’re there,” Brown said. “Americans can be very nit-picky. … You can’t go with a closed mind and get everything out of it.”

beautiful architecture

If you travel for adventure and to make memories, you will enjoy Cuba.

And now is the time to go, before the country is affected (infected?) with all that the United States has to offer.

Gonzalez, one of our tour guides, said we were lucky to come when we did. “You’re in a historical moment. Until now, most of the Americans have been good Americans,” he said, only half-joking. “But soon, we will get tourists that would have gone

to Cancun.”

Those tourists might demand the amenities they’d find on other islands, which could ruin what makes Cuba special.

“I just don’t want Cuba to become Jamaica,” Mercer said. “I don’t want to see Treasure Island down there. I don’t want to see Atlantis Resort. I don’t want to see a McDonald’s on the corner. I’d like to see this place keep its cultural identity and its sense of self and give what it has to offer to the world.”