Rural West Tennessee has played a key role in the worldwide culturing of pearls since the 1950s? Who knew? Not me. I was just out looking for a good time on I-40.

The sun was retreating into the west, the direction from which I’d fled at daybreak, looking to uncover all the hidden roadside attractions between Memphis, my adopted home, and the wilds of my verdant childhood stomping grounds in the Land Between the Lakes. But those plans had been changed by my discovery of the pearl farm, something wonderfully unexpected. The only thing left to do was kick back with an ice-cold beer to cool my spinning head, and that led me to Country Hooters, a small, white, windowless cinderblock roadhouse 600 feet from the northbound ramp of Exit 126.

There’s no identifying sign on the building, except for a notice scrawled on the red front door reading, “Must be 21,” but a series of Country Hooters billboards in a weedy garden of hand-painted signs advertising adult movies and books confirms it’s the honky-tonk in question. Holiday, Tennessee, has a God’s Country vibe, but it’s thoroughly offset by the apparent abundance of smut. A tiny church the size of a Chevy minivan sits across the street from the North 40 Truck stop, its windows dark, its parking lot as vacant as an addict’s eyes. The expansive gravel lot at Country Hooters, on the other hand, is filled with 18-wheelers in every color of the spectrum. This was the unlikely hole-in-the-wall where I assessed the day’s events.

How could I have not known that the only fresh-water pearl farm in North America was located in Camden, Tennessee? I asked myself, sucking on a frosty $4 bottle. “It’s directly across the lake from where I grew up. It’s … It’s … Omigod!”

A blurry shadow bobbing up and down in the shaded window behind me suddenly came into perfect focus. It was a naked woman, and she was dancing up a storm. That explained the $5 cover charge.

The bar was clean, air conditioned, and paneled in vintage ’70s masonite. It looked like every Dew Drop Inn I’d ever seen. Until the strippers came out … the old, old strippers, with their long, flabby, but inexplicably appealing assets. This was the ideal counterpoint to Jackson’s Casey Jones Village, with its manicured, self-conscious folksiness. It was the equal and opposite of the Cotton Patch restaurant a few exits down, where waitresses flit about in long-sleeved, floor-length Civil War-era dresses, aprons, and bonnets. This was an image of seedy rural depravity ripped right out of the original Walking Tall films, only everybody was as sweet as Cracker Barrel’s iced tea. The paranoia set in hard, and after finishing my beer and paying for a Country Hooters T-shirt (had to have the T-shirt), I left abruptly.

“Can’t you stay and have some fun with us?” a youngish dancer of perhaps 50 hard summers asked, as I made my way to the door.

“Love to,” I said, “but I’ve got a long way to drive and one’s my limit.”

Emerging into the rosy dusk I knew I wouldn’t be writing about Player Guitars, the fantastic vintage guitar store hidden in a second-story room of the strip mall at Casey Jones Village. I wouldn’t be writing about the Loretta Lynn family flea market in Buffalo or about the Civil War battlefields dotting the landscape between Memphis and the Tennessee Ridge. I would be writing about Benton County, which, like the fabled oyster, is revolting in appearance but goes down deliciously and occasionally squeezes out a luminescent bauble of rare beauty.

Treasure Cove There are two ways to reach the Tennessee Pearl Farm and Museum. You can either take the scenic route off Exit 126 or the Birdsong Road exit farther north. I opted for the long and winding road that took me past rural shake joints and gravel pit after gravel pit. Uniquely positioned between the massive man-made backwater of Kentucky Lake and the Tennessee River, Benton County has more miles of shoreline than any county in Tennessee, and its river rock has been used by NASA for building launch pads. It’s also the home of freshwater pearls so fine that when Richard Burton bought Elizabeth Taylor “La Peregrina,” a giant, tear-shaped pearl discovered by the Cortez expedition in the 1500s, Cartier jewelers turned to West Tennessee to find gems magnificent enough to match it on a necklace.

Owned and operated by Bob Keast, who continues to develop his sizable chunk of riverside property into a cozy rural resort packed with cabins and trailers, the pearl farm and museum were founded by the late John Latendresse and his wife Chessy. Since the 1950s, Lantendresse had been supplying mussel shells to Japanese pearl farmers who used them to make custom implants for seeding oysters (and other mollusks) and culturing pearls. Latendresse discovered that a handful of every thousand Tennessee freshwater mussels contained a naturally occurring pearl.

In 1980, he joined forces with Keast and began trying to grow his own pearls. “Mr. Latendresse bankrolled everything, because this was his vision,” Keast says.

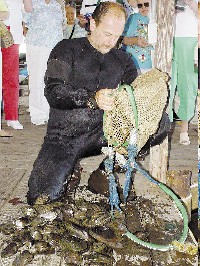

Visitors to the pearl farm can watch mussel divers, who dredge the river bottom to mine the 20 to 50 million pounds of mussel shells sold to Asian pearl farms annually. They can also learn about the exacting process of seeding and filing away the river’s washboard mussels until they’ve grown pregnant with pearly stones. One mussel opened for tourists contained four nearly perfect specimens.

“We have close to a 90 percent success rate,” Keast says, pointing out that the only other pearl farm in North America — a saltwater operation in coastal Mexico — gets pearls from only 10 percent of its implants.

The pearl farm may have a seedy front door, but Keast’s little paradise is an ideal escape for urbanites. The pearls, and a half-century relationship with the Japanese, make it far more exotic than a private dance at Country Hooters.