More than 10 years ago, I was tasked with scoring a documentary about the political machine of Boss E.H. Crump, and, as the director and I grasped for ideas, a pivotal moment came when he handed me a bootleg CD and said, “Listen to this. This is the Crump era in a nutshell.” It was the music of one man: Berl Olswanger.

Courtesy Parma Recordings

Courtesy Parma Recordings

Berl Olswanger, January 26, 1944, World War II

Olswanger was a cornerstone in the Memphis music scene in mid-20th century Memphis, both for his playing and his local music stores. Indeed, many a player today can recall taking lessons or purchasing their first instrument from the latter. They may not have even suspected how much Olswanger, aka “Mr. Music of Memphis,” was performing and composing in his prime.

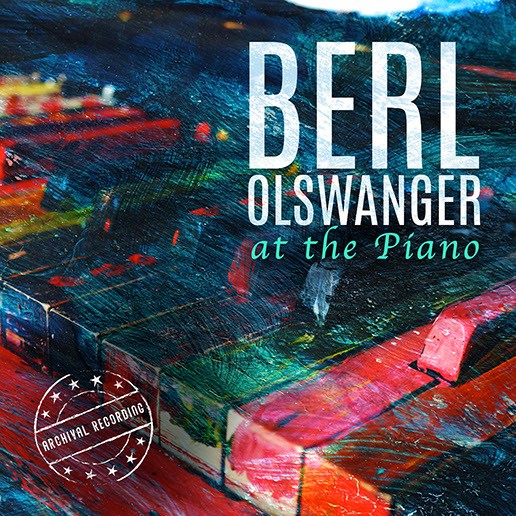

This year, his recorded output is finally being revived, starting with Friday’s release of Berl Olswanger at the Piano (Big Round Records). Though he was not a prolific recording artist, Olswanger’s piano arrangements were a feature of his daily radio programs on WMC during the 1950s. He recorded these tracks, featuring only him on piano with a spare rhythm section, in 1953.

As an indication of what this slice of Memphis music history sounded like, note that one of his triumphant moments came soon after World War 2, when impresario Ike Myers booked him for a sold-out “Middle Brow” concert at Ellis Auditorium. While “middlebrow” was a pejorative to most hipsters of the age, in the Memphis zeitgeist of the late ’40s it was a positive boon.

This new digital re-release of Olswanger’s debut can sit comfortably beside those Ferrante & Teicher albums you’ve picked up at the flea market. He focuses on the warhorses of the age, well established crowd-pleasers like “That Old Black Magic,” “Beer Barrel Polka,” or “Donkey Serenade,” as well as more respected numbers like “Stardust” or “I’ve Got it Bad and That Ain’t Good.”

And there’s an undeniable charm to these tracks. They evoke the innocence of Lawrence Welk without the unctuous visual elements, and, as with some of those “wonderful, wonderful” musicians, the playing is truly impressive. The percussive attack of Olswanger’s playing is formidable, as are the florid, cascading arpeggios up and down, that insistently fill any gaps in the melody at hand. The frenzied gymnastics of his playing may leave you somewhat breathless, and one might justifiably call it crazed, in a good way. In the right hands, this material could be part of a perfectly curated cinematic soundtrack.

And, in a sense, it’s all very true to Olswanger’s Memphis roots. Naturally, the sole original in the collection, “Berl’s Yancy,” is a medium-tempo blues, stomped out by his left hand with the ferocity of the atomic age.

Newspaper ad from 1963