August Wilson’s King Hedley II is a patience-testing tragedy as fascinating as it is frustrating. The three hour play has a disconcerting lack of focus even by Wilson’s own meandering standards. Portions of the script will confound audiences not familiar with the playwright’s earlier work. It also contains some of the Pittsburgh poet’s most soaring language and searing imagery. Wilson was ahead of his time, digging deep and exploring ideas related to market segregation, mass incarceration, and (awkwardly) gun proliferation. Time has been uncommonly kind to King Hedley, a play set in the 1980’s, in the moment before crack and the subsequent War on Drugs pulverized the poorest urban communities. For all of its structural shortcomings, it’s probably a better play today than it was when it opened.

The penultimate entry in Wilson’s Pittsburgh cycle opens with an incantation. Evil omens abound. Aunt Ester, the neighborhood’s magical matriarch dies at the age of 366. Stool-Pigeon, a “Truth sayer” (expertly portrayed by Jonathan WIlliams) divines the future from yesterday’s newspapers. Meanwhile, the play’s doomed title character kneels on a broken sidewalk, burying seeds in a crumbling patch of gravel and dust that he savagely defends: “This is good dirt.” It’s a picture ripped from Sophocles. It couldn’t be more modern or more contemporary American.

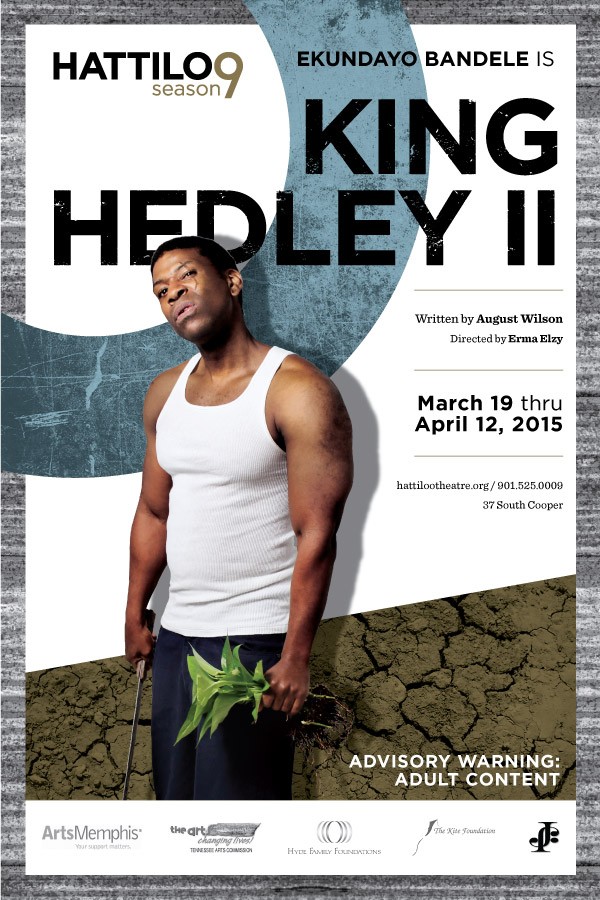

King Hedley is ferociously portrayed by a brooding and volatile Ekundayo Bandele. He doesn’t know beans about dirt, but he knows a little something about planting things. King’s fresh out of jail, having spent the past seven years behind bars for burying a man who slighted him; robbing a little boy of his daddy in the process. He aims to go straight too after he sells enough stolen refrigerators to open a video store. Yes, a video store. And yes, the pathos is thick and darkly funny, providing the audience with a nifty object lesson in the ways a play can change as it moves through time. From our perspective, Wilson’s Reagan-era story seems even more cruelly fatalistic than it was at the beginning of its theatrical life. In 2001 video shops were a declining but still a viable business. There was a faint glimmer of hope that even in this barren landscape fertilized with blood, something of lasting value might grow.

Director Erma Elzy gets solid if overly cinematic performances from Mary Ann Washington and David Muskin as Ruby, King’s absentee mother, and her slick, dice-throwing beau Elmore. Ruby’s a retired nightclub singer stuck in the past and trying to assert herself into her son’s life. Like King, Elmore’s got blood on his hands, and time in his past. But he also has luck, some common sense, and more than a little style.

Steven Fox’s Mister is a sympathetic, somewhat clownish reflection of King, his old buddy/partner in crime. He and Williams are responsible for most of the show’s real laughs, the best of which are uncomfortable. The real star of this shooting match is Ekundayo Bandele’s fantastically detailed set. It’s a stunning urban still life, populated with litter, wreathed in decrepitude and decay. It’s Pittsburgh for sure, but it could just as easily be South Memphis.

Bandele is the founding director, heart and soul of the Hattiloo Theatre, and he’s proven himself to be a capable performer, author, designer, and rainmaker. Hedley is his best on stage performance since he played Booth in a 2008 production of Suzan-Lori Parks’ Pulitzer Prize winning Topdog/Underdog.

For all of its goodness and grandeur, the script is structurally all over the place. As a result, it’s hard to imagine that even a perfect production of King Hedley II could build very much momentum. The play’s odd misfire ending is also in serious need of better framing. But since its founding, the Hattiloo has shown a steadfast commitment to staging the complete works of August Wilson. It’s a notable undertaking and this is easily one of the still-young company’s best all around efforts.