Jonathan Parker lay unconscious in a pool of his own blood on Memphis’ iconic Beale Street around 2 a.m. on Sunday, August 10th, as people gathered around him recording videos and snapping pictures of his motionless body. No one was shown alerting authorities.

Footage of the incident quickly went viral, attracting attention from local law enforcement, the Beale Street Merchants Association, and the Downtown Memphis Commission.

The three agencies agreed on a plan to limit the potential for a similar occurrence in the future. They would charge Beale visitors a $10 fee to access the street after midnight on Sunday mornings whenever the street seems overcrowded.

Paul Morris

Paul Morris

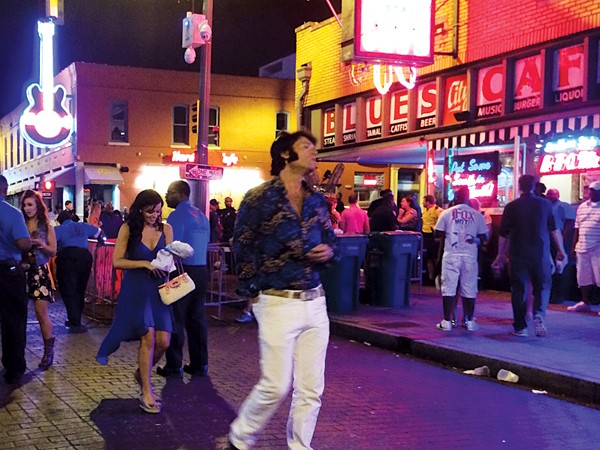

A photo snapped after midnight on the first weekend for the fee.

“We don’t want the message to be that anytime you come to Beale, you’re going to have to pay to get on. Beale will remain a free block party 99 percent of the time,” said Paul Morris, president of Downtown Memphis Commission. “We’ll only implement when necessary to ensure public safety. We don’t like it. Merchants lose money on it; they don’t like it.”

The fee was introduced the week following the Parker incident. Money collected from the fee, which will be implemented on a case-by-case basis, will be used for daytime and nighttime security patrol.

In addition to limiting crowds, the fee was introduced to make police and security more visible and make it easier for them to patrol the area, Morris said.

Some people, however, think the fee is arbitrary and could be used in a way to limit the city’s African-American and disadvantaged populations’ access to Beale Street.

Memphian Justin Bailey opposes the fee and said he refuses to pay a cover charge to walk on a public street.

“You’re talking about closing off a city street that all people should have access to and enjoy regardless of income, race, or anything else,” Bailey said. “I think it’s too much power in the hands of the merchants association without any oversight to dictate who can and who can’t go down on Beale Street. I think it’s targeted toward minorities, and I think they’re the ones who are going to be disproportionately affected by it. If you look at the make-up of Beale Street patrons, it’s us, and it’s a lot of us just on the street, which shows you that we may not want to pay a $10 entry fee to go into the club. We may just want to go hang out on the street because it’s free.”

Morris said the policy would ensure the safety of African Americans rather than have a discriminatory impact, considering they make up the majority of the street’s traffic during the wee hours of the morning on weekends. He said he hates the fee, but he found it necessary to protect Beale’s reputation.

“Put yourself in the shoes of the person who’s responsible on Sunday morning when somebody’s lying in a pool of their own blood,” Morris said. “What would you do next weekend to make sure that didn’t happen? Maybe you would do something different, but maybe you can understand that what we did is reasonable. As awkward as it is for me to have to explain to people why we have to charge that [fee], I feel a lot better about being awkward and uncomfortable about spending a $10 fee than I would feel having to explain another young man lying face down in a pool of his own blood on the street.”