JB

JB

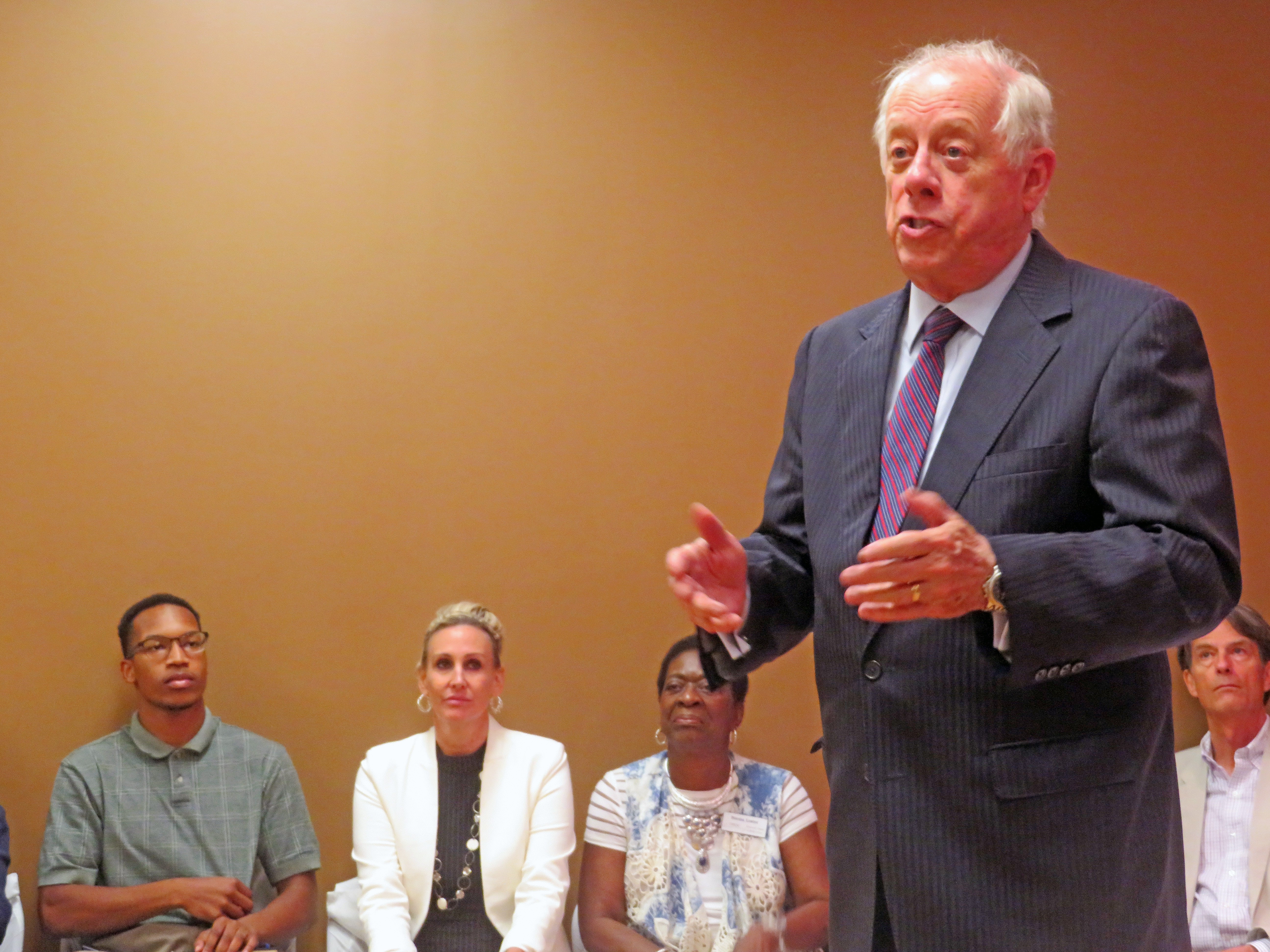

Bredesen with Memphis Democrats at the Akbari Institute

Phil Bredesen came to Memphis on Thursday, and, in a meeting thrown together at the last minute by the Shelby County Democratic Women, convincingly reintroduced himself, not as some silver-spooned entrepreneur/politician from Nashville, but as the struggling son of a single-parent family, uprooted from his original home outside Boston when, as he explained, “my father found a woman he liked better than my mother and took off.”

From that point on, Bredesen says he became “a kind of exotic person,’ a child forced as a pre-teen to relocate with his mother — a bank teller — to upstate New York, where they had to live with Bredesen’s grandmother, a seamstress with a fourth-grade education, who took in sewing to make ends meet and had to work the new arrivals into what was already a large extended family of some 12 offspring.

In the nearly 30 years of Bredesen’s celebrity in Tennessee, that brief bit of Horatio Alger autobiography, spoken with the former two-term governor’s customarily diffident delivery but without his sometimes off-putting stiffness, came off as pure revelation to the audience of 40 or so Democratic office-seekers, public figures, and off-the street activists who’d been summoned without much advance notice to a small meeting room of the Lisa Akbari World Trichology Institute, an East Memphis cosmetology enterprise run by the family of state Representative Raumesh Akbari.

As much as anything policy-wise that Bredesen said during the hour or so he stayed with the SCDW crowd — on his desire to create jobs and a universal health-care program, to work across the political aisle if elected and meanwhile to run a positive campaign — his connection with the audience was based on that initial presentation of himself as a modest person, lucky in life, who wanted above all to pass on the opportunity for good fortune to others.

It conferred credibility on his espousal of Memphis — an exciting volatile town like Chicago, he said — as the hotbed of Democratic votes and hopes in Tennessee, and, as the main source of the support he needs to win. (This kind of appeal always seems to work in Memphis, which, however, is by actual measure much less of a dependable Democratic bellwether than metropolitan Nashville, which consistently elects Democratic officials across all racial, class, and ethnic lines at a rate that Memphis cannot match. Bredesen himself is a case in point.)

In any case, Bredesen did in fact seem right at home in the bosom of this representative crowd of Memphis Democrats, to whom he — or, more strictly, one of the young helpers with him — promised to open an office of his candidacy on South Highland, in the University of Memphis area, sometime in the next two weeks.

When he’d heard last year that Republican Senator Bob Corker would not be running for re-election and he started getting telephone calls “from around the state” (and from Democrats around the nation eager to retake the Senate), Bredesen said he had first to satisfy himself that a run would not be a “suicide mission.”

Obviously, he decided it wouldn’t be. And if he truly needed the enthusiasm of Memphis Democrats to kindle his hopes of reentering political life as state’s newest U.S. Senator, then — based on the warmth of his reception among the party cadres on Thursday — he seemed to have a good basis for it.