Like the most famous resident of Cabrini-Green, J. J. “Dynamite” Evans, Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) is a painter. But the Downtown Chicago neighborhood he inhabits is quite different from Good Times.

In the 1970s, Cabrini-Green was notorious for violence and a symbol of inescapable, generational Black poverty — the go-to example of everything that was wrong with the concept of “public housing.” In 1992, Cabrini-Green was the setting for Candyman. Director Bernard Rose, who had made his name creating classic music videos for Frankie Goes To Hollywood, switched the setting of the Clive Barker story “The Forbidden” from Liverpool to Chicago in order to explore themes of race and class in America, while delivering the chills and gore horror audiences demand.

Memorably portrayed by Tony Todd, the Candyman was a hook-handed spectral killer who appears when you say his name five times while looking in a mirror. But Candyman is as much a victim as he is a boogeyman. Like Freddy Krueger, he was killed by an angry mob, and comes back to haunt the people in the neighborhood. (The mob rubbed their victim with honeycombs, and he was stung almost to death before being lit on fire. As someone with a stinging insect phobia, I found that part especially traumatizing.) But Candyman’s backstory as a Reconstruction-era painter who was lynched because he was romantically involved with a white girl gives the film a layer of meaning rare in the horror genre of the time. It also makes it a perfect property to revisit among our current moment of thoughtful horror.

Written and produced by Jordan Peele and directed by Nia DaCosta, this Candyman is a direct sequel to the 1992 film. Now, instead of a crumbling public housing project, Anthony lives in a swanky high-rise with his art dealer girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris). She believes in him, but he’s having a hard time breaking into the art world, until he uncovers the legend of the Candyman. Soon, inspiration becomes obsession. His first installation based on the Candyman mythos, where he hangs a mirror in Brianna’s gallery and dares people to defy the urban myth, ends predictably badly. But that only stokes Anthony’s smoldering psychosis. As the gruesome murders pile up, the press and the art world’s interest in the artist’s work grows. His deep dive into the bloody history of Cabrini-Green uncovers his own connection to the original Candyman.

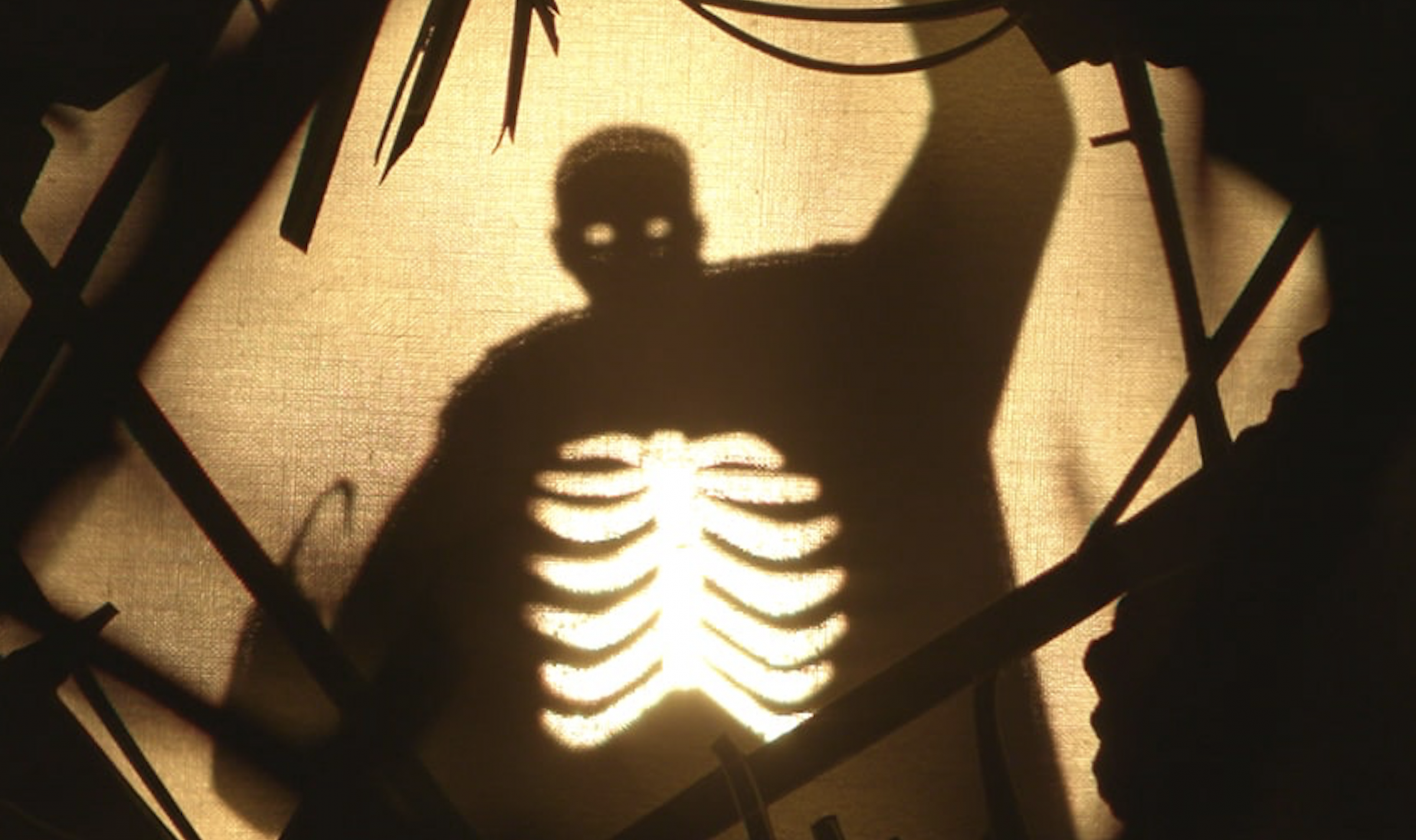

What’s great about Candyman is DaCosta’s direction. Depicting a spectral villain who appears only in mirrors gives her plenty of opportunity for creative shots and staging. For flashbacks, she uses some beautiful shadow puppet work that brought to mind Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed. When Anthony, visiting the University of Chicago to find the files of the first film’s protagonist Helen Lyle, steps into the mirrored interior of an elevator, you clench the armrest, just knowing some crazy stuff is about to go down.

DaCosta has a pair of dynamite leads. Abdul-Mateen is, as always, magnetic on screen. Like the best actors from the glory days of ’80s horror, he shares the audience’s disbelief at the weirdness taking over his life. Parris carves out her own character as neither stupid victim or savvy final girl, but an educated woman whose rationality won’t let her believe the supernatural menace she is facing until it is almost too late.

The weakest part of Candyman is the script, which is frankly kind of a mess. Maybe it’s because Peele and his Twilight Zone collaborator Win Rosenfeld are too dedicated to connecting this film to the first one. It’s episodic, prone to going down rabbit holes (or, to remain thematic, listening to the voice of the beehive) when it needs to be cultivating narrative drive. The critique of artist-led gentrification is solid, if a little too self-hating. The real villains of the story, the forces of capital who are bankrolling this forced social change for their own enrichment, are completely absent. There are some great individual scenes, but when the climax tries to weave all the half-wound threads together, it kind of falls apart. The writers should have taken the advice they writes for one art critic in the film: “You can really make the story your own, but some of the specifics should stay consistent.”