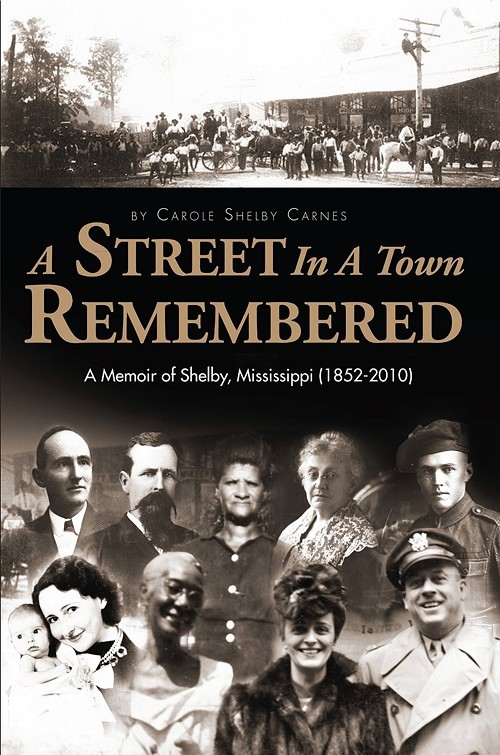

“I hope no one thinks this is a sentimental story,” Carole Shelby Carnes said recently of A Street in a Town Remembered: A Memoir of Shelby, Mississippi (1852-2010) (Nautilus Publishing).

“I’m no Southern sentimentalist. My idea was to try to capture what it felt like to live in the Delta at the time. I wanted it to be remembered. And if I didn’t do that, then I didn’t succeed.”

[jump]

Carnes was on the phone from her home in Oxford, England, where she’s lived for decades with her husband (and distant cousin), the writer and world traveler Shelby Tucker. And in case you’re wondering, yes indeed, “Shelby” gave name to Shelby County, Tennessee. “Carnes” gave name to a street in Memphis, Tennessee. So too another family name and Memphis street: Cooper. Turns out, Carnes’ book signing in Memphis late last year was on that very street, at 936 S. Cooper, home of Burke’s Book Store. But the bigger book signing on the author’s tour, which took her also to New Orleans and Oxford (Mississippi, not England), was in Cleveland (Mississippi, not Ohio).

“I saw people in Cleveland, I’d never heard of or hadn’t seen in 65 years!” Carnes said of that signing in Cleveland, and among them was a member of the Chow family — the same family that once operated a Chinese grocery store in Shelby and that sent one daughter to Stanford, another daughter to Newcomb, which is where Carnes went to college too before later earning a law degree.

“The Delta was very good to them,” Carnes said of the Chows. The Delta was very good to the Shelby and Poitevent families, the author’s forebears. In A Street in a Town Remembered, Carnes traces her own long lineages — in tales told in the voice of her mother and according to Carnes’ own memories of the place and the times — back to the 19th century and to a time when the land was cleared of forests and swamps and early settlers dealt with the original settlers: Native Americans.

The early plantation families were followed by, in addition to the Chinese, a cosmopolitan mix of Italians, Jews, Poles, and Middle Easterners, whom Carnes grew up referring to as “Assyrians.” And in among the white families — rich or poor — there were a far larger number of African Americans, among them Octavia Jackson.

“Octavia was unforgettable,” Carnes said. “She’s been dead for 48 years, and even today, if I mention her name to those who remember her, a smile breaks out. She was just such a complete individual.”

Unforgettable too: the young man whom Carnes, a teenager at the time, met at the dances held throughout the Delta for the sons and daughters of white planters: William Eggleston. In our conversation, Carnes recalled the photography exhibit of Eggleston’s work that she saw in London several years ago, but she called him “totally individual” even when she first met him and he introduced her to the first hi-fi set she’d ever seen and to the music of Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Muddy Waters.

In her book, Carnes also recalls the buffet suppers that preceded those dances — light suppers served on Limoges china but with only a fine-silver fork, no knife, to cut the ham. Which is why, the author writes, she often sent a serving of ham off her plate and onto the floor, then to be kicked under a chair.

“I’m 74, but I still miss the dances,” Carnes admitted. “You never felt like you came from Shelby or Rosedale or Marigold. You came from the Delta.”

Her mother, May, was born in Memphis, “capital of the Delta.” It was Memphis, not Jackson, where husbands often did their banking business and wives just as often did their shopping. The Gartley-Ramsey Hospital in Memphis was also where many from the Delta went for treatment, including shock treatments. Carnes doesn’t shy away from describing it in A Street in a Town Remembered. She didn’t shy away from talking about it by phone:

“Gartley-Ramsey was a nice hospital, then it became a mental hospital. But the Delta kept it filled either way — women mostly. They didn’t have anything to do! It was too hot to garden. They didn’t ride horses. Society drove them crazy, and that hospital was part of society. My generation of women were educated. We went off to do things. And it wasn’t the first and second generations of women in the Delta either [at Gartley-Ramsey]. It was the third and fourth generations. They were the ones caught in the ‘trap.’”

These days, Carnes doesn’t travel as she once did with her husband, Shelby. (Someone needs to stay home and look after the couple’s Jack Russells.) And she no longer practices law, as she once did in England and the United States. Today, the couple live in a late-19th-century house originally built for railway workmen.

Carnes described Oxford, England, as a kind of village that makes day-to-day activities (not to mention doctor appointments) easier. But she’s also lived in New York, Washington, and New Orleans. She was “called to the Bar” in England and Wales in 1974. And she’s hitchhiked, with her husband, around East Africa (the couple married in Zanzibar in 1976), North Africa, and Europe.

Shelby is still into hitchhiking, often on the back of motorcycles (to “someplace awfully disagreeable,” according to Carnes). But she does still travel some (southern India was on her agenda when we spoke), and she returns to Shelby, Mississippi, where she still owns land inherited from her father. And she still misses things about the Delta — the season of fall; the site of cotton fields — though her family home has been torn down, as so many homes have on that street in Shelby.

As far as future writing plans, Carnes reported that her next book is a love story — between two Jack Russells — and she’s calling it Tender Is the Bite. Another book idea, a cookbook, will be based on the recipes of Octavia Jackson, but that will take some doing: testing the recipes, Carnes said.

A Street in a Town Remembered took some doing too.

“Part one [on the author’s earliest extended family members and Native Americans in the Delta] was the most challenging, because I didn’t want it to sound like a genealogical book. I rewrote it eight times,” Carnes said. But she certainly didn’t lack for materials.

“I had a trunk with old letters and documents — letters my grandfather wrote to my grandmother. I had a number of family genealogical books too, and most impressive was a history of Bolivar County. Families in the 1920s and ’30s also wrote their histories, and one of the contributors wrote on the Shelbys.

“And then there was my mother, who would tell a story so many times that I could hardly forget it. Shelby took down my mother’s stories, and once I found them, I knew I could go on with the book.”

But as in most working manuscripts, Carnes said that she took a look at the first draft and pronounced it awful. She reworked it. She rewrote it. Nautilus in Oxford, Mississippi, agreed to publish it. Not until then had her husband read it. And as Shelby Tucker wrote in an email:

“Knowing how ferociously critical I am when reverting to a previous typescript of my own work and not wanting to discourage her, I did not read Carole’s book, 10 years in the making, until it was published; then I sat down to deal with a marital duty. By page 50, I was hooked. Gosh, the girl could write!”

No, it is not a “good” book, he told Carole. He called it a “wonderful” book.

Not the least of the wonders in A Street in a Town Remembered, there’s the fact that Carnes has those twin gifts no true-blue deep Southerner is without: a vivid memory to go with a natural-born talent for storytelling. No, she’s no sentimentalist. Nor is she an apologist, though there’s plenty in these pages for white Southern society to be sorry for. Plenty here to be proud of, thankful for, too. Best then that not just some of it but all of it be remembered. Author’s measure of success in this her debut book: goal met. •