This week’s column faces me with a happy predicament — how to write critically about a book I unequivocally loved? Some novels are puzzle boxes, devices of impossible intricacy meant to delight the intellect. Some take a different form — a raw, beating heart, oozing pathos and humanity. Sarah Langan’s Good Neighbors (Simon & Schuster) is both things, and more. It wrecked me, left me in tears twice, and if the past three days are any indication, Good Neighbors will live rent-free in my mind for a long time to come.

When the novel opens, the Wilde family has already worn out its welcome on suburban Maple Street. It isn’t anything they did, exactly. Sure, they could stand to take better care of their lawn, but it’s really about who they are.

Arlo Wilde, charting-musician-turned-office-supply-salesperson, with monster-movie-themed tattoos covering his track marks, likes to sit on the front porch and burn through packs of Parliaments. Gertie freezes up in social situations, leaving a big, fake smile on her face, a remnant from her beauty pageant days. She wears cheap jewelry, and her shirts are cut too low. Larry, their youngest, is going through a phase — he’s bright, but socially, he’s developing slowly. And poor Julia, pimply and pubescent, had to move to a new town at life’s most awkward stage, and now finds herself trying to fit in with a group of kids who’ve known each other since before they could speak.

As a family, the Wildes are damaged but brave, ever attempting to rise above hidden scars far more grisly than Arlo’s track marks.

David Zaugh, Zaugh Photography

David Zaugh, Zaugh Photography

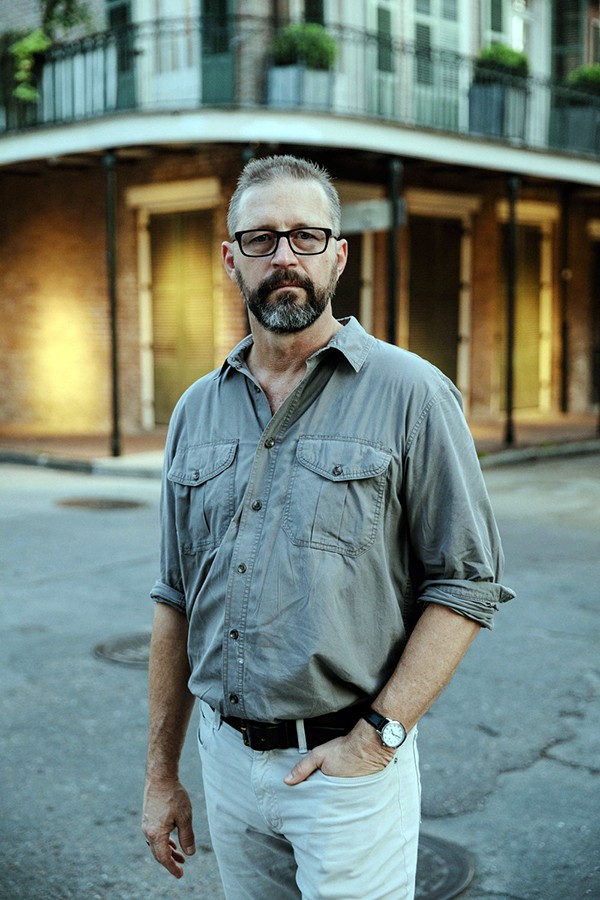

Sarah Langan

When the novel begins, with a Fourth of July block party, Maple Street’s de facto leader Rhea Schroeder is on the outs with Gertie, ostensibly her best friend. In fact, both the Wilde women are feuding with the Schroeders, it seems, as there’s friction between Julia and Rhea’s daughter, Shelly. That drama is upstaged, though, when a sinkhole opens up in the park that borders the neighborhood. Ominous, hinting at hidden dangers, it spews candy-apple-scented fumes, a clear indication that something deadly lurks, hidden, under Maple Street.

Somehow, about a month after the novel’s beginning, the resentment bubbling under the surface of Maple Street overflows and leads to a series of murders. Good Neighbors makes no bones about that — each page takes the reader inexorably closer to catastrophe.

Langan could teach a master class in suspense. She peppers the plot with interstitial chapters taken from “real-life” newspaper clippings, articles, and Hollywood Babylon-style books about the infamous Maple Street Murders. As a result, every plot point feels tragically inevitable.

“There’s this thing that happens to people who’ve grown up with violence. It changes their hardwiring,” Langan writes. “They don’t react to threats like regular civilians. They do extremes. They’re too docile over small things but they go apeshit over the big stuff. In other words, they’re prone to violence.”

Langan lays out her pieces with a watchmaker’s precision, setting up the circumstances that lead to the Maple Street Murders. What’s terrifying is how common those circumstances turn out to be. In Good Neighbors, they’re newish neighbors who don’t quite fit in, a sinkhole, an oppressive and record-breaking heatwave, a tanked economy (glimpsed in the margins), a worsening environmental crisis, and a family with secrets. It’s generational trauma and PTSD and a community, a microcosm of America, struggling under the weight of these intersectional crises.

In other words, it could happen here, too.

Novel at Home: Sarah Langan with Grady Hendrix, authors in conversation in live online launch party for Good Neighbors, Tuesday, February 2nd, at 6 p.m. Event is free with registration.

William Widmer

William Widmer