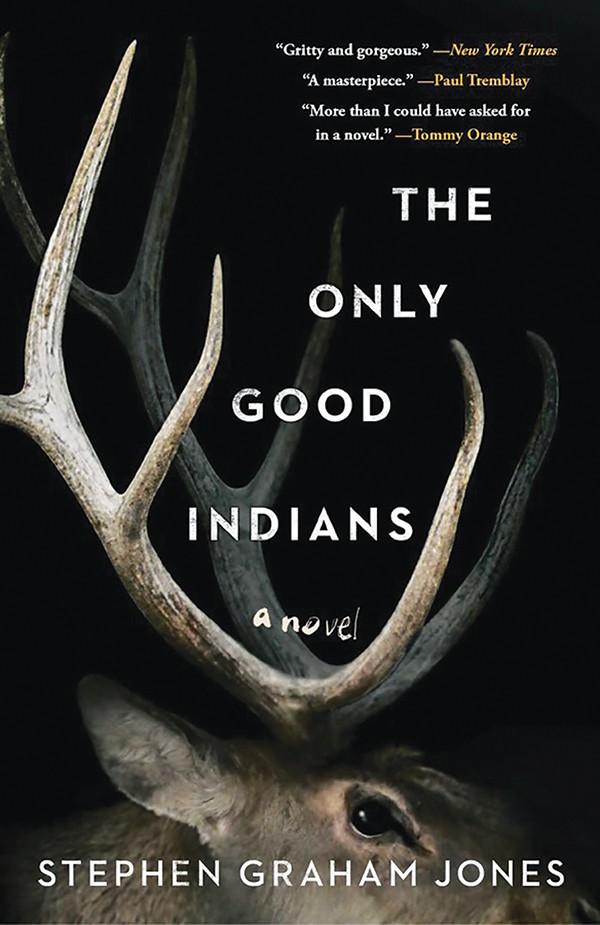

In two mesmerizing marathon sessions, I read Stephen Graham Jones’ The Only Good Indians (Saga Press) over the July 4th weekend. There could have been no better atmosphere for Jones’ literary horror novel of revenge, cultural identity, and tradition on a Blackfoot reservation. Amid nationwide calls to address racial inequities, President Donald Trump gathered a crowd of mostly white Americans at a once-sacred site to the Lakota Sioux, one that was promised to them in perpetuity, to deliver a pro-nationalist, jingoistic tirade against cancel culture.

“Our nation is witnessing a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values, and indoctrinate our children,” the president claimed, seemingly without realizing the irony of making that statement on that land. Erasure and indoctrination were exactly the fates of Native Americans. So perhaps I was primed to be rattled by Jones’ heartbreakingly powerful novel. Or maybe The Only Good Indians is just that damn good.

Courtesy Stephen Graham Jones

Courtesy Stephen Graham Jones

Stephen Graham Jones

The novel takes its name from what folklorist Wolfgang Mieder calls “particularly hateful invective” directed at the United States’ indigenous population, and that wry, dark humor informs the perspectives of the novel’s protagonists — four young members of the Blackfoot tribe. The men are irrefutably aware of the terrifying statistics that characterize the lives of so many like them. Their inner monologues are rife with remembered and imagined arrests, friends’ suicides, car crashes, and addiction. They know what society expects from them.

Still, for all the social commentary and supernatural fright deftly woven into The Only Good Indians, it’s in the honest portrayal of his characters that Jones truly shines. Ten years ago, Ricky Bibs, Lewis A. Clarke, Gabriel Cross Guns, and Cassidy Thinks Twice went on an illegal elk hunt in the elders’ lands, what the quartet called the “Thanksgiving Classic.” Now they find they must pay the price for their casually unleashed carnage.

The young men feel real enough to reach out from the page and shake the reader. Jones’ horror is rooted in humanity, in the author’s surfeit of heart. His characters are flawed and unerringly human, defined by or in denial of their guilt, which is why it hurts so much to read their stories.

“We’re from where we’re from,” Shaney, one of Lewis’ coworkers, tells him early in the novel. “Scars are part of the deal, aren’t they?” The line serves as a warning to the reader as well. Keep reading, if you dare, but be warned — in these pages, even the triumphs are tinged with tragedy.

Denorah Cross Guns, Gabe’s driven, basketball ace of a daughter, gives the reader someone to root for — and some serious stakes. For the monsters in The Only Good Indians play by the old rules, and punishments are heaped upon innocent children as much as on their parents, the transgressors.

Of late, Jones has been labeled the “Jordan Peele of horror literature,” and the moniker is earned as much for the overall strength of the work as for the social commentary within. If Peele’s Get Out was a masterwork — funny, frightening in ways both immediately visceral and creeping and intellectual, brilliantly composed — so is Jones’ most recent novel. His characters are natural. The book’s plot is a furious page-turner; its message, timely and potent. And The Only Good Indians works as well as a work of environmental horror, warning that to harm our home is to invite its revenge.

Jones’ The Only Good Indians is heartbreaking, exciting, and terrifying in equal measure. It’s the clear frontrunner for my favorite book of the year — for its masterful execution, for its humanity and honesty, and because it has haunted me since I turned the last page.

Holly Whitfield

Holly Whitfield  Book cover art and design by Joel Amat Güell

Book cover art and design by Joel Amat Güell  Kim McCarthy

Kim McCarthy

Melissa C. Beckman

Melissa C. Beckman

Burke’s Book Store

Burke’s Book Store